A Pert British Cruising Catamaran

Issue 145: July/Aug 2022

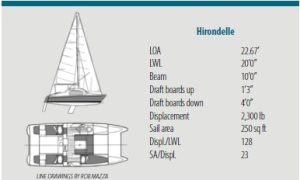

Forty-some years ago, empty-nesters Richard and Sheila Olin sold their business in Chicago, and with their two daughters in college, boarded their British-built, 23-foot Hirondelle catamaran and headed south. No more Windy City, no more snowy winters.

The 23-foot Hirondelle scoots handily off the wind in flat water on Sarasota Bay.

In 1987, they sold the Hirondelle and bought a Gemini 3100 catamaran for more spacious Florida cruising. About five years ago they sold the Gemini to a persistent acquaintance who wanted the boat. But unwilling to be boatless, and eschewing the monohull option, Richard searched for a small cruising catamaran and settled on another 23-foot Hirondelle, listed for sale in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Once a multihuller, always a multihuller; level sailing and speed are persuasive. Indeed, in the 1960s Richard had owned a 35-foot Lodestar trimaran, also built in the U.K. His current

Twin companionways access each hull. The molded coamings make for comfortable backrests. Note the well enclosure for the outboard that allows it to be lifted clear of the water to prevent drag.

boat, Full Circle, has allowed him to keep sailing safely well into his 80s, though Sheila has since passed.

History

This clever little catamaran was introduced in 1968, designed by Chris Hammond and built by the British yard Brian Carvill & Associates. According to a feature story in the September/October 1994 issue of Multihulls magazine, more than 300 were sold. The subject of that article was the announcement of the Hirondelle Family, an updated model of the same length but with 2 feet of extra beam, a roomier interior thanks also to extending the cabin forward a bit, and the option of the innovative Aero Rig in which the headsail and mainsail are set on the same rotating boom.

Here, however, we’ll focus on the original Hirondelle. The early 1970s models are now called Mk Is; Mk IIs had shorter masts; and late ’70s models are listed as Mk IIIs and feature fixed keels as opposed to retractable boards, as well as upgraded interior features.

Design and Construction

The twin rudders raise for shallow water but do not kick up in a grounding. Access to the swim platform and ladder is easy through an opening in the stern pulpit.

Hammond decided on symmetrical hulls of sufficient width for single berths. To maximize interior volume, the flat-ish sheer actually has some reverse to it.

The original daggerboards make for superior upwind performance, a talent in which multihulls are generally inferior to monohulls. The trade-off is additional manufacturing cost and complexity, i.e., trunks and raising/lowering lines and hardware. In modern catamarans, the choice of daggerboards versus fixed keels is a quick and decisive insight into the boat’s intended service—cruise or race, or at least better sailing performance.

The rudder boards raise but do not kick up; if they strike bottom, the aft ends of the trunks are designed to break away.

Bridge clearance and configuration affect two things: wave slap and interior volume. Richard Olin reports minimal slapping noise though he mostly sails in protected waters.

The space forward between the hulls is mostly solid, that is, fiberglass, with just the most forward foot or so filled by a “tramp” or netting. On a small boat of just 23 feet, the extra weight of the solid deck is a concession to the Hirondelle’s cruising side, as several lockers are stowage for ground tackle, fenders, and lines. Richard says wave slapping under the bridge hasn’t been noticeable on Full Circle, adding it was more of an issue with the Gemini.

The foredeck is mostly solid, with a small area covered by netting. Each hull has an anchor roller, so a bridle would minimize “sailing” while anchored.

While little information about construction is available, the hull is single-skin fiberglass; one owner says the deck is cored with balsa. There are no liners in the hulls or on the underside of the deck. While seemingly crude, at least all deck hardware fasteners are easily accessible.

Accommodations

As with most cruising catamarans, the bridge deck is where crew gather for meals and evening games before lights out. The U-shaped dinette easily accommodates four, and the table lowers to form a large berth, somewhat disturbed by the compression post under the mast. The table is held in the up position by a clamp attached to the compression post; there are fixed backrests outboard.

With the dinette table down, the main cabin is dominated by a queen-size berth.

Depending on crew number, the two single berths in the aft ends of the hulls and the single forward in the starboard hull may suffice. The head with portable toilet is forward in the port hull, and a small galley with a two-burner stovetop is abaft the dinette in the bridge deck. A small, molded sink is in the starboard hull, handy to the galley.

The single berth aft in the starboard hull. No need for lee cloths.

There are numerous cubbies for stowing stuff, all without doors; remember that multihull performance is predicated on light weight, beginning with the absence of ballast and perpetuated throughout design and construction by eliminating unnecessary features, such as cubbie doors. That said, photos of the Mk III show a few refinements such as a privacy door to the head and nicer upholstery around the dinette, including padded backrests.

Rig

According to sailboatdata.com, the original design was soon modified with a shorter rig, carrying just 220 square feet of sail. One can only speculate on the reason, though safety—keeping the boat right side up—is a strong possibility.

On Full Circle, Richard has opted for a roller furling headsail and mainsail; a man in his 80s doesn’t need to be teetering around the foredeck and cabintop. Richard can set and furl both sails from the safety of the cockpit. The stock Hirondelle had a roller furling boom, but Richard opted for roller furling behind the mast because he feels it gives better sail shape and can be handled from the cockpit.

The main cabin is dominated by the dinette, which easily seats four. When the table is lowered, this becomes a queen-size berth, at left.

Photo by Neil Gruber.

Under Sail

Many years ago, a Hirondelle won the multihull class in the Around the Isle of Wight race, though the particulars are not known to this writer. I have, however, enjoyed a daysail with Richard on Sarasota Bay and found performance to be lively. He says it’s best to lower both boards, which we did. We did not measure tacking angles that day, but Richard says it tacks through 130 degrees.

Full Circle is equipped with a Raymarine ST1000 autopilot that Richard controls with a remote. As crew there was absolutely nothing for me to do, as he has everything from dock lines to sheets to steering set up for “old-person sailing.” The two rudders and tillers are connected by a steering bar that is easy to tend if and when he wants to hand steer.

Because of the boat’s lightness and absence of ballast, maintaining momentum when depowered while steering through a tack is best accomplished by a gentle turn rather than quickly throwing the helm hard over. The risk is stalling the boat, though Richard says that “sailing backward with helm reversed provides an easy way to relieve the stall.”

The modest galley is basically a platform for a camp stove.

Manufacturer’s sailing instructions that accompanied the boat emphasize that catamarans can capsize and not return to level. The message is to reduce sail early. Regarding beam and close reaching, the instructions state: “Except on a very close reach, beware of luffing in response to gusts, because an abrupt luff may aggravate heel by banking up water against the lee hull and centreboard. On some catamarans the technique is to bear away during gusts in order to help the boat absorb the wind energy by accelerating; but this is not appropriate for Hirondelle, which accelerates better if held straight. When reaching along the line of largish waves remember that a wave front both rolls the boat to leeward and lifts it into bigger exposure to wind at the same instant.”

I include this here less as a tip on a specific handling techniques and more as an alert that multihulls behave differently than monohulls, and it will take a newcomer a bit of time to adjust, though it’s not difficult and it is rewarding.

Additional instructions are thorough and cover such situations as flying a spinnaker, heaving to, and board height (in certain conditions half boards are recommended).

An outboard motor mounted in a well aft in the cockpit provides auxiliary power. While the boat can handle up to 25 horsepower, Richard finds his new fourstroke, 8-hp Honda more than adequate and wonderfully quiet. Short- and long-shaft motors work, though the short can cavitate in certain wave states, and the long may risk running aground if not tilted, as it projects below hull level. Fuel tanks are stowed under the port and starboard helm seats.

25 horsepower, Richard finds his new fourstroke, 8-hp Honda more than adequate and wonderfully quiet. Short- and long-shaft motors work, though the short can cavitate in certain wave states, and the long may risk running aground if not tilted, as it projects below hull level. Fuel tanks are stowed under the port and starboard helm seats.

The Hirondelle is a versatile family cruiser for short cruises and spirited daysails, with speeds surpassing most monohulls of similar length. Construction is adequate but dated.

An Internet search for used Mk I Hirondelles found a few for sale in the U.S. Models from 1971 and 1973 were listed for $14,000 and $14,400, respectively. More are for sale in the U.K.

Dan Spurr is Good Old Boat’s boat review editor. He’s also the author of several books on boat ownership, among them Heart of Glass, a history of fiberglass boatbuilding, and the memoir Steered by the Falling Stars.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com