The family business that sparked a DIY sail- and canvas-making revolution.

Issue 147: Nov/Dec 2022

When I call Matt Grant, vice president of Sailrite, to interview him for this article, I’m surprised to find myself on hold, the third person in line. I listen to a minute or two of classical music before he picks up, and I learn the reason why.

Matt sits next to the customer service pool, the people who answer the phones, so that he’s accessible when a customer has a particularly difficult question. I’m impressed that the VP of a business with nearly 100 employees still takes calls from customers.

“I’m a boater myself,” says Matt. “So that’s part of the enjoyment of the job. I like talking to the customers.” (This story mingles interview quotes with others from the Sailrite website, used with permission.)

It’s a hands-on approach that’s been a cornerstone of Sailrite since Matt’s parents, Jim and Connie Grant, founded the company in 1969. Today, Sailrite is the be-all and end-all among sailors when it comes to DIY fabricating in canvas; many a Sailrite machine has circled the world onboard. It remains a strongly family-based business, with Matt and his wife and Sailrite president, Hallie, now leading the company, Matt’s brother, Eric Grant, spearheading the company’s how-to online videos for DIYers, and a third generation of Grants injecting new energy and ideas across departments.

Matt says he and Hallie counsel the young Grants frequently that, “You don’t have to be enormous. You just need to be happy and helpful. And that’s really what we’re all about. Can we be happy and helpful? And I’m happy to say, at this point we’ve accomplished that.”

Headlong Into Hands On

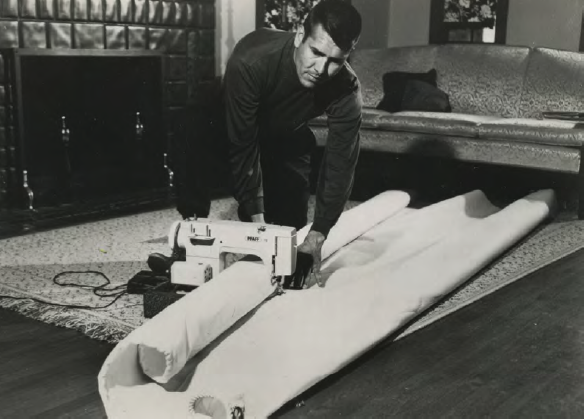

As the story goes, it all started with sailing. Jim Grant needed a new set of sails for racing in the Cal 20 Nationals, but the local sailmaker couldn’t make them in time. So, Jim bought the materials and made the sails himself. Not only did he finish them in time for the regatta, but he also won second place.

Naturally, other sailors were interested in doing the same. Jim, who until that time had worked as a college professor, wanted to provide sailors with instruction and materials for DIY canvas and sailmaking. In 1976, he launched a correspondence course on sailmaking called the “Sailmaker’s Series” so amateurs could learn how to make their own sails.

It was a pioneering concept at the time, and Sailrite began to grow rapidly. That same year, needing more affordable space for the business as well as a more centralized location, Jim and Connie decided to move the Sailrite headquarters from California to a remodeled barn in Columbia City, Indiana—also the Grant family’s hometown.

As Jim delved deeper into sailmaking, he realized that there weren’t many good amateur sailmaker sewing machines on the market. Sailmaking requires a heavy-duty sewing machine with a zigzag and a long stitch length, an ability to handle heavy materials and feed fabric easily, all while being portable.

It was a tall order, but Jim was determined to build a sewing machine tailored to amateur sailmakers. He modified an existing sewing machine, the Brother® TZB651, increasing its power by adding a larger diameter balance wheel with an idler pully and a two-belt drive system. Launched in 1981, this improved Brother sewing machine, known as the Sailrite Sailmaker Sewing Machine, “became the most well-known and respected portable zigzag sewing machine for sail and canvas workers,” Matt said.

The Second Generation

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Matt was attending college studying business, but he worked at Sailrite, tuning and shipping sewing machine orders when he wasn’t in class. It proved to be an education in its own right.

“I learned that sewing machines can be fickle to tune consistently to get equal performance from one unit to the next,” Matt said. “It took me years to hone my skills.”

He was also fine-tuning his business skills. Matt felt that a $1,999 sewing machine was too expensive for most boating DIYers.

“I wrote a college paper on the subject and convinced myself that I could come up with a less expensive model to supplement the Sailrite Sailmaker model,” he said. “I had theorized that a price point of $499 would increase the market by 500 units annually.”

Using the same approach his father had taken—building up an existing machine—Matt developed a new, more affordable, model. Though some tradeoffs were necessary to keep the cost down, the Yachtsman sewing machine was a hit and achieved Matt’s original goal of selling 500 machines in a year.

However, he wasn’t yet satisfied. “We reached the conclusion that we needed control of the manufacturing process to create machines to serve our niche,” Matt said.

Working closely with his colleague and head sewing machine technician, Duane Crisp, Matt set out to custom design a sewing machine for sailmakers. It would be a machine with a zigzag stitch, walking foot, and feature a longer stitch length (important because it reduces puckering in canvas making). It also had to be lightweight and portable.

“It was an arduous process,” Matt said. But in the end, they developed a sewing machine so unique that they decided to patent the design. According to Matt, it was the first machine designed as a portable, heavy-duty sewing machine for sewing sails, canvas, and upholstery.

One of its key features was the grip and pulling strength of the feeding mechanism, so the machine was dubbed the Ultrafeed.

They found a manufacturer in Taiwan, though Matt did the final tuning and adjustments on each machine before shipping to the customer.

“The process was slow, and I soon found that to produce a quality product I would be spending day and night at work,” Matt said. “For a few years I remember dreading Christmas, as I basically lived at work in order to ship machines to arrive on time.”

The Ultrafeed launched in 2000 and was a huge success. Sales boomed and Matt continued to refine his design. “The machine really became a marvel,” he said.

So marvelous, that it spawned a slew of copycats. Matt discovered that their manufacturer in Taiwan had been selling Ultrafeed sewing machines to companies producing reproductions.

“The machine looked like it was going to be so successful that look-alike units hit the market before our patent had been completely issued,” Matt explained. “It took a few years for us to figure this out, but the damage was done.”

Sailrite sued and eventually drove many of the look-alike producers off the market, but years of legal battles took their toll.

Matt was happy when he could finally get back to innovating. In the period that followed, he created several custom Ultrafeed parts, like the PosiPin® Safety Shear and Monster II Balance Wheel.

The parts were manufactured in the U.S. “Our decision was partially predicated on keeping our ideas from being copied, but it was equally because we cared about jobs in America,” Matt said.

During this time, he also hired and trained staff to fine-tune the machines and built a team of full-time sewing machine technicians.

The Ultrafeed became Sailrite’s flagship sewing machine and continues to evolve. Most recently, in 2021, Sailrite launched a new quarter-horsepower motor, the WorkerB® Power Pack motor system.

“No other portable machine has this amount of power, starting torque, and slow speed control,” said Matt. He’s proud of what they’ve built.

The Family Grows

In 2021, Sailrite expanded its head-quarters by 31,200 square feet to accommodate a growing workforce and inventory. The expansion came with a change—a chance for Matt to have his own office. Until very recently, he shared his office with Sailrite’s president and a pivotal figure in the company’s history: his wife, Hallie Grant.

“I wouldn’t have wanted to do this, nor could I have done this without Hallie,” said Matt. “She’s been instrumental to the growth of the business.”

Matt and Hallie were high school sweethearts. The two met in Columbia City and both went to Indiana University, though neither of them graduated there.

“We got so involved in the business,” said Matt. They decided to return to Columbia City to work at Sailrite full-time. “We would work eight to five and then jump in a car and finish our classes in the evening.”

Hallie has an uncanny gut for business and the seeming ability to predict the next big thing. Long before most businesses had a website landing page, she proposed selling Sailrite’s products online and found a company that would build them a website for $20,000.

“I thought she was crazy,” says Matt. “My wife, myself, my mother, and father sat in a hot dog stand in downtown Columbia City. The three of us were like, ‘This is never going to work,’ and Hallie’s like, ‘Trust me.’ So, ultimately, we said, ‘Okay, give it a shot.’”

Sailrite.com went live in 1997, a whole three years before Walmart launched its e-commerce store. “All of a sudden, the internet took off like wildfire,” said Matt.

Jim and Eric Grant, Matt’s brother, were some of the first to see the potential of online videos for DIYers. The Sailrite team had found it challenging to explain complex concepts and techniques over the phone to customers. So, they began publishing videos on Silverlight, an early Microsoft product for web videos.

When YouTube came along, Hallie was the one to convince the team to switch platforms. Matt thought that Silverlight was the way to go, but Hallie was certain that YouTube was the future.

“We went to YouTube and I thought, ‘Oh, this is a horrible idea because all of our content is owned by them,’ ” said Matt. “Well, obviously, you know how that story played out. You’ve probably never heard of Silverlight.”

Sailrite joined YouTube in September of 2010 and has since grown to over 350,000 subscribers. Their extensive catalog of how-to videos is a DIYer’s dream. You can learn just about anything from making a simple throw pillow to building an asymmetrical cruising spinnaker.

Matt’s brother, Eric (aka “The Project Guy”), is often the one you’ll see in the videos, teaching sewing techniques (how to sew a zipper) or demonstrating a project step-by-step (how to make a sunshade). The videos are extremely well produced and deeply researched. Matt says that Eric will sometimes build a project two or three times for a video, learning and fine-tuning his approach.

“Eric uses our equipment probably more than anybody in the world, so he knows it extremely well,” he says.

Stitching a Future

In 2004, Jim and Connie retired. With Matt and Hallie at the helm, Sailrite now employs 85-95 employees, including several Grant family members.

Jim, who has always been passionate about computers and programming, enjoys tinkering with Sailrite’s Fabric Calculator.

“He just loves working on that fabric calculator,” Matt says. “It’s very accurate and it gives you the ability to figure out exactly how much fabric and everything else you need to make your cushions, whether it’s for a boat, patio, or bench seat. He sort of sees it as his legacy at this point.”

The third generation of Grants is also involved. Eric’s son, Seth Grant, does a lot of the camera work for the YouTube videos. Matt and Hallie have two sons and a daughter. Their oldest, Zach Grant, has been working for the company for seven years and is Sailrite’s marketing manager. Tanner Grant has worked in the business for four years and is the purchasing manager, and their youngest, Sierra, who is still in college, picks orders in the shipping department part-time.

“They have huge ideas and big dreams for what we can do in the future,” Matt says. “We’ll see. We tell them, as long as you’re happy doing what you’re doing and as long as you feel like you’re providing a service that is good for your customers, you will succeed in business.”

Matt says he also enjoys encouraging first-timers who have a project but are new to the skills and the machines and uncertain how to begin.

“I always tell people, you just start. Watch a few videos. They’ll teach you more than you know. Watch a few videos on relevant projects—we should have a video on just about anything. Every project you do, you will get better. And don’t be afraid to make mistakes. Sometimes you’ll end up redoing things,” he says. “But the emails that I get from customers who have purchased machines, who have asked that question in the past, usually go this way: They say, ‘I am so thankful that I decided to try this, and I have paid for this machine ten times over with the stuff that I’ve done.’

“And if you do that it’s hard to argue because it’s really not that complicated when you get right down to it…And everything you learn seems to transfer over to the next project.”

Fiona McGlynn, a Good Old Boat contributing editor, cruised from Canada to Australia on a 35-foot boat with her husband, Robin. Fiona lives north of 59 degrees and runs WaterborneMag.com, a site dedicated to millennial sailing culture.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com