A stout double-ender for cruising

I’ve heard that New England sailors have seawater running through their veins and after meeting Margaret Pesaturo, I would say it’s true. Her grandparents were boatbuilders in Nova Scotia and she grew up near Massachusetts Bay, spending summers boating on Martha’s Vineyard.

The interior doesn’t employ a liner; exposed fiberglass is painted white with the overhead and V-berth sides paneled (called a ceiling even though it’s on the vertical hull sides) with varnished white pine strips. Photo by Joe Cloidt.

Margaret married her husband Ron in the early 1980s, and after buying an Able 20, they cruised the waters of Buzzards Bay. While waiting for their fall haulout, they came across a Frances 26 named Sintram III in a neighboring boatyard, fell in love with it, and using grocery money as a down payment, bought her, renaming her Mystique. They continued sailing the New England coastline until Ron’s health failed, and Margaret found herself singlehanding Mystique.

Years later, Margaret met Captain Thomas, dockmaster and delivery captain. Together they delivered yachts all through New England with Thomas giving the helm to Margaret on sailboat trips. When Thomas passed away in 2013, Margaret and Mystique were sailing solo again; until she met Stan, a licensed captain and sailor.

Together, they share their love of the ocean and lighthouses, spending summers in Maine and sailing Florida waters in the winter. Margaret says at 78, she is starting to slow down and has put Mystique up for sale. While she enjoys winter sailing in the south, Margaret says it’s just not the same as sailing on Buzzards Bay—perhaps it’s that New England seawater in her veins.

History

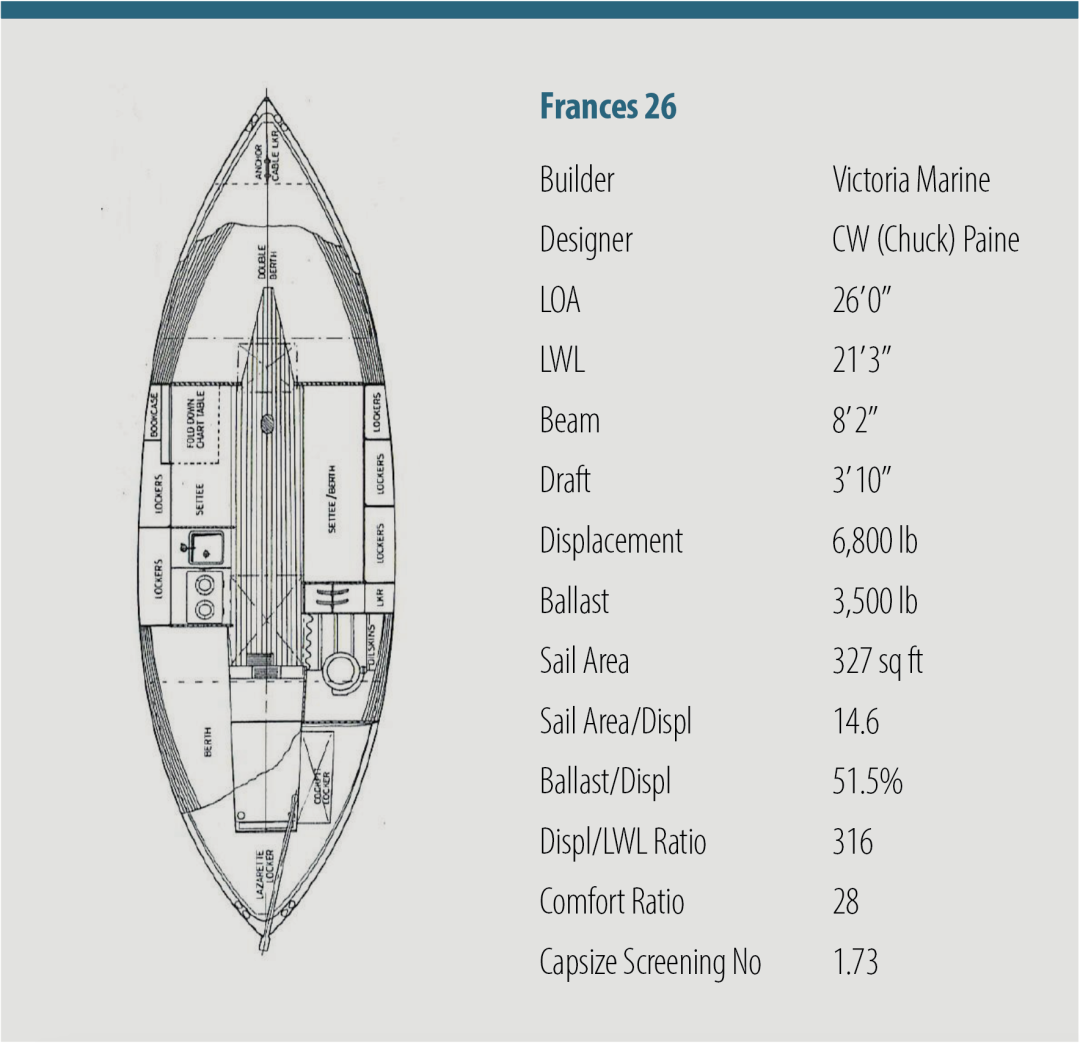

The Frances, a traditional looking double-ender, was designed by C.W. (Chuck) Paine in 1974 as his ideal cruising boat. Growing up on Narragansett Bay Rhode Island, Paine was surrounded by classic sailing yachts, and inspired by traditional Colin Archer designs and the success of the Westsail 32. So he designed his flush-deck Frances to be a modern version of a double-ended cruiser.

Paine built the first Frances from wood in a borrowed shed in Camden, Maine. As the boat was nearing completion, he met Tom Morris who had recently started Morris Yachts. The pair struck a deal for Morris to build the boat in fiberglass, naming it the Frances 26. The design also garnered interest from builders in Britian where Morris and Paine licensed the design to Victoria Marine. The UK boatyard built over 150 boats and in the mid-1980s Morris started importing them to the US when the dollar-to-pound exchange rate was favorable; Mystique is an import model. After several business mergers, Victoria Marine discontinued building sailboats in the mid-1990s.

The two builders produced over 200 boats and also offered build plans for the Frances 26 for the DIY sailor. Paine went on to design the Victoria 30, 34 and 38 for Victoria Marine and worked with Morris Yachts on more than a dozen more designs. Paine is now semi-retired and focuses on “small but extremely elegant daysailers.”

Design

Paine originally designed the Frances to be a small, efficient, low-maintenance cruiser that could survive a gale at sea. Starting with the seakeeping qualities of full keel designs, Paine modified the hull shape to improve its windward performance. He sharpened the hull entry angle closer to that of a racing yacht and gave the canoe body a tight radius curve where it meets the keel. The shape is more rounded than a traditional wineglass when viewed from the bow and gives the keel a taller vertical profile which helps to prevent leeway. The hull shape makes for a narrow bilge that is deep at the aft end which Margaret says limits the size of the electric bilge pump that can be placed there.

Mystique, a Victoria Marine-built model, has a short house or cabintop, leaving the entire area forward of the mast flush. Photo by Joe Cloidt.

The rounded hull does have lower initial stability than a hull with firm bilges but Paine compensated for this by giving the boat a high ballast/displacement ratio of 51 percent. This gives the boat an easy roll to its motion that stiffens up as the boat heels farther over. To keep the crew safe and dry, Paine designed the Frances 26 with high freeboard and 4-inch bulwarks at the foredeck and around the cockpit. Early production models retained Paine’s flush-deck design but a short trunk cabin house was soon added that gave standing headroom. A full coachroof was added in 1982 with these models named Victoria 26.

Construction

The Frances 26 has a solid fiberglass hull and a balsa-cored deck. The (plywood or fiberglass?) deck is epoxied to a 2-inch-wide hull flange, through-bolted on 8-inch centers and then glassed over with three layers of fiberglass tape to form a strong and leak proof joint. A teak cap rail finishes off the joint. Margaret reports Mystique has never had a problem with leaks in this area.

The 3500-pound lead keel is through-bolted to the hull using ¾-inch bronze bolts, then glassed over. The fiberglass rudder is attached to the hull with a set of three pintles and gudgeons and is topped off with an oak head and ash tiller. There is a small gap between the keel and rudder that is prone to catching lobster pot lines so Mystique’s previous owner fitted an extension to the end of the keel that blocks the gap.

Lateral loads from the rigging are handled by a wood plank crossmember that runs the width of the beam behind the mast and ties into the deck/hull joint. Interior bulkheads and furniture are built from ½-inch marine-grade plywood and are glassed into the hull and deck. Deck-mounted hardware is backed up by either stainless-steel or plywood backing plates. The overall fit and finish of the fiberglass and cabinetry is high quality. Mystique was stored on the hard under shrinkwrap during the winter in Massachusetts and her gelcoat and non-skid deck are still in very good condition for a 41-year-old boat.

The shrouds terminate at U-bolts on deck which are secured to chainplates through-bolted to bulkheads. Note how the uppers don’t run fairly through the spreader tip. Photos by Joe Cloidt.

Deck and Rigging

The Frances 26 has a tall ⅞ fractional rig and a self-tacking 100-percent jib on a club or boom. A cutter rig was an option that allowed for larger headsails and better light-air performance. Mystique has a keel-stepped Proctor single-spreader aluminum mast, and to keep things simple, sail halyards, reefing lines, and winches are kept at the mast.

Without a bowsprit or bow roller the anchor must reside on the deck and the rode must run through one of the two small chocks—not a very good ground tackle system. Photo by Joe Cloidt.

In researching the rig we found several configurations. Mystique has a somewhat unusual design with four chainplates on each side serving fore and aft lower shrouds plus two that run through the spreader tips and then to the side wall of the mast, near where the forestay attaches. The leads through the spreader tip are not fair but Margaret says this has not caused any problems. The shrouds fasten to ⅜-inch U-bolts that mount through the deck to stainless-steel chain plates located inside the cabin. The plates are bolted to ½-inch plywood knees that are taped and glassed into the deck and hull and are easily accessible for inspection. While many sailboats that have a transom-mounted rudder use a boomkin to support the backstay, the Frances 26 has the backstay tang offset to starboard, allowing the tiller a full range of motion.

A single jib sheet runs back to the cockpit winch on the starboard side. The mainsail is trimmed by a four-part tackle attached at mid-boom and to the bridge deck in front of the companionway. Margaret uses Mystique as a daysailer so ground tackle is kept to a minimum. A Danforth anchor is stowed on the foredeck in chocks with the anchor rode fed through a small bow roller and secured to a samson post.

The cockpit seatbacks are varnished teak which look traditional although some owners say their height digs into their lower back. There is a small lazarette at the aft end of the cockpit footwell for storage and allows access to exhaust and tank vent hose through hulls. A locker under the starboard bench has room for fenders, cushions and deck gear.

The engine compartment is between the head and quarter berth and has precious little room for maintenance. Photo by Joe Cloidt.

Mechanical

The Frances 26 has minimal, easy-to-maintain and repair systems. Engine options included a Yanmar 2GM10 and a Volvo MD5B. Owners’ opinions on how well these single-cylinder engines run vary from smooth and quiet to “damned unearthly,” with my experience being the latter. Margaret said while noisy, Mystique Yanmar with its two-bladed prop does smooth out around 5 knots. Quick access to the engine is through a panel on top of the engine box, which can be removed for more working room. A panel in the quarter berth allows service to the rear of the engine, stuffing box, and 10-gallon fuel tank. The single-lever engine control is mounted on the side of the cockpit footwell which I found was easy to bump with my leg.

The engine control panel and a basic electric panel with switches and fuses are tucked under the companionway top step where they are protected from weather. Start and house batteries are located under the companionway bottom step and the quarter berth. Electrical loads are minimal on Mystique—a few lights, VHF radio and depth finder. Shorepower was never installed.

Accommodations

The very tight head has enough space for the toilet and a pair of legs. No sink. That space is economized for other parts of the interior. Photo by Joe Cloidt

When I first looked into Mystique’s cabin, my reaction was “It’s bigger on the inside!” The trunk cabin house, with its 6-foot headroom, and no forward bulkhead, gives the cabin a spacious feel not expected on a boat of this size. Coming down from the cockpit, there is a small head compartment to starboard with a marine toilet, no sink, and a curtain for privacy. A small holding tank is under the starboard settee. Just forward of the head is a hanging locker. To port is a quarter berth and a small but functional galley that has a gimbled two-burner kerosene stove and oven, a sink with a freshwater foot pump and decent storage. A lid fits over the sink to make counter space with a 15-gallon water tank located under the port settee.

The starboard settee is long enough to serve as a berth with the short port settee doubling as a seat for a fold-down chart table. The V-berth is comfortable for two although it’s a tight fit for those close to 6 feet tall, as are the other two berths. A small table stored in the V-berth can be snapped onto a collar on the mast at mealtime. Shelves and lockers line both sides of the cabin.

Margaret pointed out, as an example of British attention to detail, all the slots in the screw heads for the wood strips are aligned. Cabinetry is built from plywood covered with white Formica laminate and trimmed in varnished mahogany. The cabin sole is teak and holly. The white surfaces create a nice balance with the darker varnished wood.

Lighting is provided by several dome lights and a fixture over the galley. Natural light comes in from fixed rectangular windows on the cabin sides, two round brass portlights on the cabin house front, and a hatch on the foredeck.

Cockpits on smaller double-ended boats can feel narrow and cramped but our reviewer found the Frances 26 comfortable for two aboard. Photo by Joe Cloidt.

Underway

I met Margaret for the first time on the morning of our test sail, and she was, as I expected, a spunky 78-year-old who knew her sailing and her own mind. She explained that she prefers to handle things herself, so I stayed out of the way but did help with the dock lines. Once clear of Telemar Bay Marina in Indian Harbor Beach, Margaret raised the sails and we slowly made our way around Dragon Point to the Indian River Lagoon and the ICW.

Our test sail was on a sunny, hot day in late October that was tempered by small popcorn clouds and a gentle 10-knot northeast wind. With the light breeze, I bore off to get out of the wind shadow from Merritt Island and played with the tiller to get a feel for the boat. With its heavy displacement, the Frances 26 had a smooth, easy motion that gives it a big-boat feel.

With the outboard standing rigging, cabintop handrails and wide enough sidedecks, going forward doesn’t require gymnastics. Photo by Joe Cloidt.

The tiller gave good feedback and let me know when the sails weren’t trimmed properly. After bearing off the tiller started to load up to let me know it was time to ease the sails. Instead of easing, I let the boat round up until the tiller went light and only needed fingertip control. Once we came onto the wind, the boat heeled slightly and picked up a knot of speed. The Frances 26 is well balanced when it’s in the groove and I sailed with my hand off the tiller until a gust came up. When a puff hit us, the boat would roll gently a few degrees but was far from putting the rail in the water. Margaret says she would sail in 15-20 knots on Buzzards Bay and only buried the rail a few times.

The self-tacking jib made coming about easy but with its long keel, it is slow to tack in light air compared to a fin keel and will stall if it doesn’t have enough boat speed, which I found out twice (but in my defense, we had dropped the jib). Once around, the boat falls off a little, puts its shoulder down and picks up speed. Not a fast boat, we managed about 4 knots in the light wind although Margaret says she has sailed Mystique faster than the 5.4-knot hull speed. Due to sailing conditions, our upwind runs were limited so I didn’t get a good feel for how close to the wind the boat would sail but it is reported that with a good breeze, the Frances 26 will point within 90 degrees of the wind.

Conclusion

The Frances 26 is a simple, no frills but well-thought-out and rugged little cruiser that’s a pleasure to sail and is also pleasing to the eye. While the term cozy is sometimes used as a polite way of saying “small,” I found the Frances 26 to be cozy in a warm and comfortable way. Although not designed to be a bluewater cruiser, one hardy sailor sailed his from the UK to Australia. However, due to its small size, limited storage and tankage, this cruiser is more suited for local and coastal cruising then crossing oceans.

Still a popular design, there are several active social media sites and owners’ websites for the Frances 26, along with a wealth of information on Chuck Paine’s website. An Internet search for used Frances 26 showed most of the boats for sale were in the UK. Prices ranged from just below $20,000 up to $40,000 for a 1992 model with $30,000 being average. In the US, Margaret’s 1982 (Victoria Marine) is listed for $32,000 and a 1977 Morris built Frances 26 is for sale at $49,000.

Resources

http://www.frances26.org/lissome.php

Owner Comments

As on many boats, the quarter berth is a repository for loose gear including sail bags. Photo by Joe Cloidt.

We sailed our wonderful Lissome many thousands of miles between Puget Sound and Alaska and 18 mos. in the Pacific to New Zealand. Western Pacific and Australia. She was built by Morris Yachts in late ‘70s.

Very steady and handy for a boat of that size. We sailed everywhere because we could, and hardly used the engine. Used 12 gallons of fuel to get to NZ. Explored Vanuatu, Solomons, and Australia engineless (raw water-cooled Volvo didn’t like the tropical water!).

Nice balance between being seakindly and relatively fast. Super simple to handle inshore and offshore.

Morris quality was super high and spoiled us. Crossing the Pacific put more stress on her than she was really designed for, so we had to reinforce the connections between house and deck and the house overall.

She is beautiful and functional and the two are interwoven. She had the right balance, for us, between being really simple/minimal but safe and capable to travel far, with ease and simplicity.

Being a small boat, it was sometimes hard to beat to windward in sea conditions that slowed her down. In many cases, we had to motor sail.

Mast step had to be rebuilt by next owner, but perhaps just wear and tear?

—Peter and Pam Hayes, Portland, Oregon

I have owned a Francis 26 since January 1980, when I bought a Victoria Marine hull and deck at the London Boat Show. I completed the interior, added deck fittings, and made sails for her. I got her sailing briefly before moving back to California in 1982. The original Volvo Penta MD5A single-cylinder motor is still working.

My only voyage was down the coast of California from San Francisco to Santa Barbara in 1994. She sailed well downwind in a various conditions with the help of a Monitor servo-pendulum windvane. Stayed right on course on a broad reach all night heading out to sea. Since then I have lived on her for several years, and sailed her to the Sacramento Delta several times. She is now berthed near Rio Vista, on the Sacramento Ship Canal.

After 43 years she is still in fairly good shape, though not sailed for several years. I was pleased to see Chuck Paine’s YouTube channel that features a few videos of Francis 26 boats.

—David Westwood, Richmond, California

David White’s Felicity sailing off the coast of Maine. Photo by Ed Kenney.

My wife and I have a cutter-rigged Victoria Frances that we purchased in 2016. Felicity had at one time crossed the Atlantic but had been used more recently primarily for day sailing.

The Yanmar 1GM10 needed a rebuild as it was burning oil and could not have possibly been putting out its rated horsepower. During one sail out of Rockland ME, we found ourselves trying to power upwind into 30 knots. We barely made any headway. After that experience, we decided to repower with a Beta 16. We also swapped out the 2-blade 12-inch prop for a 4-blade 14-inch feathering prop which made a world of difference.

We think the design is close to perfection. She sails beautifully and looks gorgeous doing it. We can get to 45-degree relative wind easily. She tacks easily and is extremely well balanced.

The accommodations are necessarily tight. There are numerous variations for the interior layout. Felicity has a V-berth, which I find difficult to climb in and out of. The galley table took up far too much room, so we have designed a smaller table. I physically could not fit in the head, so we removed the marine head and added a porta-potti in a more accessible location. However, there is a great deal of accessible storage for a boat this size.

Living and cruising on board Felicity is much more like tent camping than RV camping. All of which is a small price to pay for the zen-like feeling of slipping through the water with a 10-knot breeze and a perfectly balanced rudder. I love the simplicity and feel of the stern-hung rudder and tiller. I very much like the cutter rig. We can adjust sails as the wind freshens or drops and she stays balanced from double reef main with staysail to all sails flying. Chuck has designed a new keel, and an add-on to the existing keel, to get a few more degrees to windward. I don’t find it necessary.

No build issues noted. Built to be capable of ocean crossings. Victoria did a great job.

—David White, Owls Head, Maine