An Easy-to-Sail, High-Quality Coastal Cruiser

Issue 139: July/Aug 2021

From the San Juan Islands of Washington State north to the shores of Alaska, the British Columbia coast has it all for fabulous cruising, whether ocean sailing or gunkholing. These are the home waters of Windborne, a 2006 Tartan 3400 owned by Dick and Jo-Anne Sherlock and Mike and Sue Sloan.

Dick and Mike are longtime friends who pooled their resources to purchase Windborne in 2009. Neither resides in Windborne’s homeport of Sidney, British Columbia, and work commitments limit their time, so a shared boat seemed logical. The couples have cruised separately and together on numerous occasions, a testament to the interior roominess of this 34-foot cruiser/racer. In 2014, they challenged their sailing skills and circumnavigated Vancouver Island, a 700-nautical-mile journey in the open Pacific Ocean and protected coastal waters of the Salish Sea and Johnstone Strait. The Tartan 3400 proved her worth, inspiring confidence.

History

Co-founded by Charlie Britton in the early 1960s, Tartan Yachts was established on the shores of Lake Erie in Grand River, Ohio. An early model (1968) was a 34-foot Sparkman & Stephens design. The Tartan 34 continued in production until 1978.

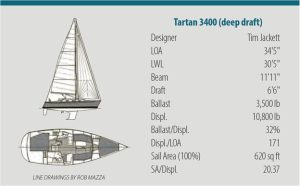

Meanwhile, working through a number of different owners, Tim Jackett became the in-house designer in the mid-’70s. He moved up the corporate ladder, designing numerous Tartan and C&C models when that famous line of racing boats was acquired by Tartan. In 1985, the Tartan 34-2 was introduced, looking very much like a cruising version of the C&Cs of the day, with a broad reverse transom and IOR influences. Move forward to 2002, and the Tartan 3400 debuted as a high-tech, fast cruiser. Renamed the 345 in 2016, the design continues to this day.

Tartan Yachts, along with its affiliate, Legacy Yachts (the powerboat arm of Tartan), suffered through recent economic downturns and has been bought by Seattle Yachts International (SYI). With an infusion of capital, SYI plans to keep Tartan in operation with Tim Jackett retaining a position on the design and management teams.

Design and Construction

Perhaps the most notable feature of the 3400 is the self-tending headsail, which simplifies tacking but precludes setting a genoa (more on this below).

The factory offered three configurations of keel design: deep draft (6 feet 6 inches), shoal draft (beavertail with bulb drawing 4 feet 11 inches), and keel/centerboard (3 feet 11 inches, board up). All are apparently interchangeable, something to consider when moving a Tartan 3400 from the deep waters of, say, the British Columbian coast to the shallow cruising grounds of the San Francisco Bay delta.

The lead keel is attached to a shallow stump with stainless steel bolts that are accessible after removing the centerline saloon table and sump pump hardware. The different keel configurations also result in differing ballast numbers: In the beavertail keel configuration ballast is 3,700 pounds, in the keel/centerboard version 4,200 pounds, and in the deep draft version 3,500 pounds.

The rudder is a spade and auxiliary power is a saildrive.

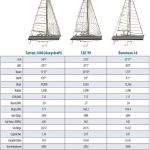

Jackett’s focus on performance is reflected in the moderately light displacement/length ratio of 171, and the sail area/displacement ratio of more than 20; a typical cruising boat is usually in the mid-teens.

This emphasis is also reflected in construction. The hull is a composite of unidirectional E-glass, epoxy resin, and linear polyurethane Corecell. The foam coring provides stiffness as well as sound and thermal insulation and has a definite strength-to-weight advantage over a standard single-skin fiberglass hull. The 3400 deck is cored with Baltek AL 600 balsa that’s replaced with solid, reinforced laminate where deck hardware is mounted. Tartan does not through-bolt deck hardware. Stainless steel fasteners are drilled and tapped into aluminum plates molded into the deck. The advantage is that deck hardware can be removed without dealing with headliners and fasteners below.

The hull-to-deck joint is the time-tested method of laying the deck on an inward-facing hull flange. A T6 aluminum flat bar is molded in, forming a full sheer-length backing plate.

Like most production boats, Tartans were finished in a white gelcoat. A number of basic colors were offered in an Awlgrip finish. While Awlgrip is an incredibly tough, long-lasting paint, the finish does suffer with time, and Windborne’s 14-year-old finish is the only cosmetic area that needs attention. I have looked at a 3400 of the same vintage with a white gelcoat finish, and the gelcoat still retains its gloss with no noticeable hairline fractures.

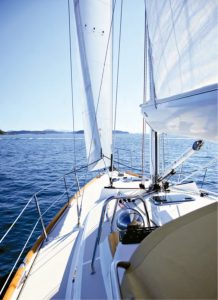

On Deck

The T-shaped cockpit stretches 7 feet from cabin to stern rail, plenty long enough to catch 40 winks on the wide seats. The cutouts for the wheel do not take up the entire width of the seats, allowing for a full stretch. Sailhandling from the helm can be a bit cumbersome because the wheel and binnacle hinder access to the sail control lines located at the cabintop edge. A wheel lock or autopilot is almost a necessity for the singlehanded sailor.

Back support against the cabin and wide coaming is excellent. The coaming has a dedicated propane locker to starboard, and a storage cubby on the port side. The engine control panel is to starboard adjacent to the binnacle, easily reached by the helmsperson.

The cabintop is somewhat busy with all the sail control lines leading to blocks at the base of the keel-stepped mast, then to turning blocks before slipping under the dodger and into the cockpit. The hardware is all first-rate and should provide years of trouble-free service.

Cabin ventilation is provided by two forward-facing hatches with a third on the foredeck over the V-berth. All eight cabin portlights are stainless steel and opening.

In the tradition of Tartan, the substantial teak toerail runs the length of the deck with cutouts for mooring cleats. The teak takes abuse from dock and fender lines as well as footwear. On Windborne, all the teak on deck is finished with high-gloss varnish. Unfortunately, accumulated deck water sits against the varnish at the stern quarters, causing the varnish to lift. Outboard, the toerail meets the hull with stainless steel trim to cover the joint.

Rig

The 3400’s double-spreader, tapered, carbon-fiber mast is painted with white Awlgrip. The 7/8 rig follows the small jib/large mainsail philosophy and is easy to control. The standing rigging is wire and the backstay is split. Although Windborne does not have an adjustable backstay, installing a tensioner would not be difficult.

As mentioned earlier, the 90-percent jib on a Harken furler is self-tacking with a curved track athwartships just forward of the mast. There is just one jib sheet and it follows all the other control lines back to the cockpit across the cabintop. Two Harken 32 self-tailing winches on the cabintop lend muscle to these lines. Two Harken 40 self-tailing winches at the aft end of the cockpit coaming provide control points for the asymmetrical spinnaker. This is a big main, and sheeting in hard is quite the task. Mainsail sheeting is mid-boom and controlled from the cockpit with the cabintop winches.

The boom is unique in that it’s designed as a trough to hold the mainsail. Constructed of carbon fiber, it’s probably as light as it can be, but still constitutes weight and mass aloft. It is quite a departure from a conventional boom and would take this sailor some time to get used to. The mast and boom hardware, including the outhaul track located inside the trough, is all first rate and appears more than sufficient in strength. Windborne is equipped with lazy jacks. Dropping the full-batten main is as simple as letting the halyard go. The sail drops into the trough with little prompting. A fabric sail cover, attached to the inside of the trough, is zipped up, and you’re done!

Interior

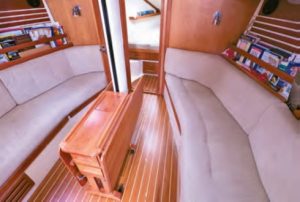

Entry over the low bridge deck and into Windborne’s delightfully bright cabin is a sinful pleasure. Warm cherry wood with off-white upholstery creates a very light, open feeling.

The head is immediately to starboard, with a toilet, molded vanity countertop and sink, and separate shower. At the end of the shower compartment is a small wet locker that is, for practical purposes, too small for more than one set of raingear. Ventilation for the head includes an overhead hatch and opening portlight.

To port of the companionway is a half-moon shaped galley. Among its unusual features is the small island in which the sink is located, opposite the rest of the layout. On Windborne, the large icebox, which has easy top- and front-loading access, has been converted to a refrigerator with the compressor mounted behind the portside settee. The downside to this interesting layout is that anyone wishing access to the aft cabin has to move the chef out of the way.

The settees would not be considered seagoing berths—too much curve and too narrow at the ends. There are maple-fronted storage compartments port and starboard and exposed bookracks leading to the forward bulkhead. There is also storage behind the settee cushions but none under the seats where the water tanks are located. The mast comes through the overhead about 33 inches aft of the bulkhead and supports the folding saloon table, which includes storage for bottles and small paraphernalia.

Forward of the saloon is the V-berth, a small but adequate space. The door swings open into the saloon, which allows room between the bulkhead and berth for dressing. The berth is only 5 feet 8 inches long and 5 feet wide at the shoulders—relatively small for many adults. A hanging locker to port, a locker to starboard, and drawers under the berth provide storage. A large opening hatch and two opening ports supply ventilation.

Mechanical

Windborne has a 3YM 30 Yanmar diesel under the companionway, facing aft and driving a Yanmar 20 saildrive. Three access points make servicing easy. Water for the heat exchanger enters the system through the saildrive leg with the shut-off cock readily available. A large side panel in the aft cabin allows access to the oil, fuel, and air filters along with the oil dipstick. Access to the alternator belt and raw-water pump is a bit more difficult with cabinetry and batteries hindering the space. Sound insulation is 1-inch foam sandwiched with a silver Mylar face—effective and easy to clean.

On Windborne, the saildrive came equipped with an Eliche Radice bronze, two-blade, folding propeller providing a comfortable cruising speed of 5.6 knots at 2,800 rpm. With a maximum continuous rpm of 3,200, more speed is available, but Dick likes this combina-tion. With the soft engine mounts on the saildrive (no shaft alignment issues), noise and vibration are minimal in the cockpit, and conversation under power is easy without raised voices.

Windborne has three 12-volt wet-cell batteries in a compartment under the aft cabin mattress. Two are the house battery and the third is a separate starting battery. With a little reconfiguration, a fourth could be included to bolster the house bank.

The Tartan 3400 carries 25 gallons of fuel in a single aluminum tank in the cockpit locker and 60 gallons of water in two aluminum tanks under the settees in the saloon. Pressure water and a dual-source (engine heat and 120-volt) hot water tank are standard from the factory. A 20-gallon holding tank is located well aft under the cabin mattress.

Underway

I was fortunate to sail Windborne twice; both trips impressed me. On a warm spring day, Dick and I motored out onto the Sidney waterfront in blustery 15- to 20-knot winds. The full-batten mainsail was soon up and the jib rolled out. Windborne surged to weather on a tight reach, her deep 6-foot-6-inch keel digging into the water. The knotmeter soon tagged 7 knots, whitecaps dancing against the dark blue hull. Windborne was dry and stable, heeling in a very controlled manner in the gusts. Dick said that when going to windward with 20 knots across the deck, he would be thinking of a first reef in the main.

There was a 1.5-knot current against us, and measuring tacking angles proved difficult. The 100 degrees reported by Dick seemed reasonable. With the current setup, the boat wouldn’t point as high as the keel/spade rudder combination should suggest—a tradeoff perhaps for the convenience of having a self-tacking jib. And speaking of tacking, it was so simple! Check for nearby vessels and turn the wheel.

On a reach with the sheets eased, steering was light and sensitive. On a broad reach, the large mainsail began to disrupt wind flow over the small jib. Dick reported that this is where the asymmetrical spinnaker comes into play. But with the large mainsail pulling hard, we were rushing over hull speed anyway, and it seemed prudent to leave the chute in the bag.

Later in the summer, Dick and I went out again in light air. The Tartan 3400 surprised me in winds under 10 knots. On a reach with 6 knots of apparent wind, Windborne sailed easily at 6 knots. This is something I expect on a light, nimble racer, not a cruising boat with minimal headsail. Dick tells me this is where he often uses the big asymmetrical, as the predominately light sailing conditions of the Pacific Northwest summers offer a large range of sailing angles.

Several PHRF fleets rate the boat at 120 seconds per mile; for comparison, a Catalina 34-2 is 150 and a Beneteau 35 is 126.

The downside to the self-tacking jib is the inability to point as high as similar boats with overlapping genoas. Of course, installing a genoa track and an overlapping sail is not out of the question, but bearing off a few degrees is a small price to pay for the convenience of the self-tacking feature.

Conclusion

The Tartan 3400 is a well-designed, spacious yacht that not only performs well on the water but does so with character and class. From beautiful lines to technical innovations, the Tartan is a boat that has stood the test of time and will do so into the future. I was impressed with her speed in light air and solid feel when the chop picked up. The few shortfalls I encountered can either be remedied with a little effort (adjustable backstay, genoa track), or can be worked around (all lines to the cabintop, out of reach of the helm).

The Tartan 3400 is a well-designed, spacious yacht that not only performs well on the water but does so with character and class. From beautiful lines to technical innovations, the Tartan is a boat that has stood the test of time and will do so into the future. I was impressed with her speed in light air and solid feel when the chop picked up. The few shortfalls I encountered can either be remedied with a little effort (adjustable backstay, genoa track), or can be worked around (all lines to the cabintop, out of reach of the helm).

The engineering is solid and the hardware impeccable. This is not an inexpensive boat, but the attention to design and construction detail is second to none. Although not set up as an ocean-crossing cruiser, the Tartan has the ability to handle the rough stuff. Having been there and done that, I wouldn’t hesitate to take her outside of Vancouver Island, romping down waves in the prevailing 30-plus summer westerlies. This is a boat that could also close reach to windward in those same conditions.

Few Tartan 3400s make it to the previously owned market. When they do, they generally range from $100,000 to $140,000. The more recent and identical Tartan 345 nearly doubles that price.

Bert Vermeer and his wife, Carey, live in a sailor’s paradise. They have been sailing the coast of British Columbia for more than 30 years. Natasha, an Islander Bahama 30, is their fourth boat (after a Balboa 20, an O’Day 25, and another Bahama 30). Bert tends to rebuild his boats from the keel up. Now, as a retired police officer, he also maintains and repairs boats for several non-resident owners.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com