Working alongside shipwrights shines a new light on hands-on.

Issue 135: Nov/Dec 2020

Not long ago, as I was combing through the employment want ads, one job leaped from the page. A shop that specialized in the restoration of wooden boats was looking for help. Boats! I could be making money refinishing a sailboat! I called the number and Ken Lavalette, owner of the company, answered the phone.

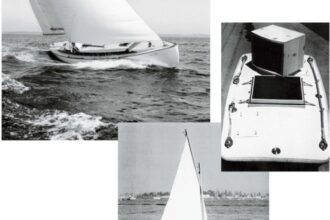

I learned he was looking for a shipwright, actually. I acknowledged I wasn’t a shipwright, but I excitedly described the work I’d done on my 1974 Grampian 2-34. Then I told him about the refinishing work I’d done on my previous boat, a Grampian Classic 31, about how the previous owner saw her and remarked that she “looked like a fine piece of furniture.” Mr. Lavalette graciously decided to let me have a go as a finisher, and we agreed to a trial working period, perhaps a day or two.

A couple of days later, there I was at the doorstep of Woodwind Yachts in Nestleton, Ontario. The intoxicating scent of wood wafted with undertones of varnish. My eyes widened at the scene before me.

Boats from skeletons to highly polished hulls rested in cradles covering the floor. The tapping of mallets and hammers punctuated the soft hissing of sandpaper, and these purposeful sounds echoed throughout the space. Shelves, cupboards, and cubby holes organized the tools of this boat restoration trade.

I soon met Luke, tall and friendly; I was to be his apprentice.

“Today, you are going to work on a canoe.”

I followed Luke to where a prized Walter Walker canoe sat on two padded sawhorses. (I quickly learned that priceless boats were literally part of the woodwork here. The shop had restored Kittyhawk, which had belonged to Orville Wright, and owners from around the world sent their beloveds here for mending and refurbishing.) My job was to scrape old varnish from inside the canoe and then to sand.

Luke showed me how to sharpen a scraper. He put the tool in a vise, drew a large file across the edge several times, then removed the tool and drew the scraper across the top of his thumbnail; an ultra-thin layer of nail curled up before the blade.

We sat on cushioned seats on rollers. Three bright floodlights illuminated the canoe’s interior. Luke explained that scraping and sanding had to be done in a certain direction based on the position of the clench nails in the canoe’s ribs, as well as the direction of the wood’s grain. He kept an eye on my work and periodically offered tips.

I loved that the work was tedious and repetitive, though the physical aspect was more than I had considered. All the while, I soaked in the shop banter between workers, each on a different boat. I learned that most of the boats had been there for months, a few had been there for years—but not neglected, rather, worked on daily, exactingly. I saw a hull that appeared to be encapsulated in glass, gorgeous and shiny, just before work started to sand and apply another coat. Simply gorgeous wasn’t what they were after; everyone in the shop was after excellence.

I came to appreciate that excellence was only possible when a worker had years of time and experience in the field. I saw firsthand that their labors of love are intensive and physically demanding. Boats and the work they need often require contortions into tight, cramped quarters, making a difficult and painstaking job even more so.

Patience and craftsmanship were on full display in every one of my co-workers. I slowly came to accept that I was way out of my league in this shop.

When the workday was done, I talked again with Ken, the owner. I told him how much I’d enjoyed the work, acknowledged my work was proper, and that I realized how painfully slow I was. I let him know that my middle-aged body was having a hard time with…all of it. I told him that I realized I’d confused my love of pastime for love of work. On my own sailboats, my pace wasn’t a consideration. I could stop and take breaks often and whenever. I could work two hours and call it a day, or not show up at all.

I thanked him again for the opportunity, accepted payment for my work, and we said our goodbyes with a handshake.

I remain grateful for the experience, even though it was only a day. I’d always loved working on my own boat; now, somehow, that task seems even sweeter.

Deborah Kelso has been sailing on Ontario’s Lake Simcoe for the past 16 years. She enjoys sailing and working on her Grampian 2-34. For 12 years prior, she doted on her Grampian 31.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com