A cherished daily ritual helps a passagemaking sailor transition to cruising

Issue 150: May/June 2023

Waking up in the V-berth of mySabre 30, Ora Kali, I can tell by the sun shining through the companionway hatch that we are facing west. There’s always a slight frisson of fear at this moment; Did the wind shift in the night and turn our anchorage into a lee shore? But all appears to be well.

Without disturbing Tom, I swivel and slide my feet onto the cool cabin sole. My motion makes the boat rock, destroying the illusion that we are somewhere else. The Maine air is chilly, and I grab a fleece jacket before climbing the few stairs to look through the cockpit at the boat behind us, then ashore where I can see the floats of the Winter Harbor Yacht Club and hear early morning traffic. A sense of well-being floods my heart as I duck below and start making coffee.

On land, my routine includes boiling water in an electric kettle and heating milk in an electric frother. This doesn’t work on 12-volt power, but as a passagemaking sailor at heart, I long ago learned to manage coffee on a boat. Living and sailing aboard our Peterson 44, Oddly Enough, in the Pacific for 10 years, we were either underway, when I had the 5 to 8 a.m. watch, at anchor, or in a marina, with whole coffee beans, a hand grinder and stovetop espresso pot, and a large, comfortable galley.

Leisurely coastal cruising, however, is unfamiliar territory, and Ora Kali is a small boat whose limitations I’m still getting used to. But this is a time of day I can ill afford to miss, when I write, listen to the weather, look at charts, and plan the day while Tom enjoys extra time in bed.

The Maine coast is said to be at its best late in the season, when visiting yachts head south and the locals come out. So Tom and I waited until all our summer house guests had gone before dropping the mooring line in Frenchman Bay the last week in August, and with plenty of food and water on board, sailed out to explore as far into the heart of Maine’s coastal cruising grounds as possible in three weeks. Though I learned to sail here as a child on small boats, we never cruised outside this big, sheltered body of water to the north and east of Mount Desert Island. And the year before, when we delivered Ora Kali up from New Jersey, we did so in large hops, so most of this will be new grounds.

After leaving our anchorage near the yacht club, we slip into the Gulf of Maine and head southwest. I hoped by not pushing for an early start that the wind would soon pick up, but as we cruise along the rugged south coast of Mount Desert Island we are still motorsailing, with Ora Kali’s rattling 3-cylinder engine drowning out my thoughts. We plan to stop at some of the offshore islands, including the Cranberry Isles, a cluster of five islands that are only a couple of miles south but loom large for Frenchman Bay sailors as an offshore destination. Islesford, a harbor town on Little Cranberry Island, has shops, galleries, and a museum and sounds inviting, but with the National Weather Service forecasting strong southwesterly winds in 24 hours, the harbor looks a little too exposed.

We know from delivering Ora Kali the previous summer that the big bight on the north side of Swan’s Island provides excellent protection from the southwest if we anchor well inside off Roderick Head. Roderick Head is quiet, great for observing diving birds and an eagle fishing, but isn’t quite the island experience we’d hoped for, so in the afternoon we reanchor in the mooring field off the ferry dock.

The anchorage is wide open to the south and the chop is too fierce to stay long, but we row ashore, talk with the woman who runs the ferry office, and then explore a couple of miles of island road, our sea legs causing us to roll as we walk. There are “for sale” signs around and we know from real estate listings and our chat with the ferry manager that Swan’s Island is changing, with newcomers buying up land at a furious pandemic pace. But the picturesque houses don’t yet reflect the change, and the locals in pickup trucks take time to wave at us.

Maine’s inhabited offshore islands have a mystique partly because, like Darwin’s finches, they evolved differently in their isolation. Residents formed unique communities that served their physical and social needs. Our short walk is not enough to tease out this one’s individuality. We’d like to spend a full day exploring, perhaps walking to Burnt Coat Harbor where the fishing fleet lives, but we catch a glimpse of Ora Kali bouncing frantically at anchor in the exposed ferry harbor and hurry back to return her to safer anchorage.

When the weather clears, we ask each other, Where do we go next? What should determine this?

On a boat, I have always thrived on the need to get somewhere. At sea, a crew meets the day’s challenges as they come. You have the choice to leave port on a good weather window for your next destination, then afterward you meet what comes head to head. Nobody will appear miraculously to extract you when something happens. Some might find this terrifying; I like being in charge of my destiny.

Last year’s delivery trip started the shift away from passagemaking. We stopped every night, but the trip was broken into individual day voyages whose goal was driven by the need to get to Sorrento while the weather was good. But what drives a sailor when there’s nothing one HAS to do? This current cruise feels like the amorphousness of retirement.

It doesn’t take long before I find some answers. To be successful, a leisurely Maine coastal cruiser has to choose destinations that provide shelter for the boat and crew in Short Voyageschangeable weather. Cruising the Caribbean in winter didn’t throw up such challenges. All that was required for a secure anchorage was a shallow bay on the lee side of an island, which almost always had boats in it as identifiers. Here I’m not comfortable in an open bay with the wide ocean at my back, and the changeability of the wind direction makes it imperative for morning route planning to identify not just one well-sheltered anchorage for the night, but also a backup.

Then there’s the pursuit of pretty rather than just spectacular. The two nights we spend in a tiny cut in the shore of Wreck Island provide both. Before heading there, we stopped at Billings Diesel & Marine in Stonington, at one end of the Deer Island Thorofare, where we picked up a mooring, washed clothes, and took showers. Last year from that spot we had front row seats to a constant parade in the channel of big and small boats. The Billings Marine harbormaster tells us this year’s yacht traffic is way down, as people who went sailing in the early days of the pandemic were now back to other activities. Even the large local fishing fleet is less active, with the price of lobster depressed enough that fisherfolk made the hard choice early in summer not to set their traps.

Wreck Island is two miles south of Stonington in what’s known as Merchant Row, a series of over 50 mostly uninhabited islands between Deer Isle and even more remote Isle au Haut, which got its name from the French explorer Samuel de Champlain. When he arrived the island was home to the Abenaki people, a good reminder that most of the places we visit were once inhabited and worked by native peoples.

Wreck is on a small lagoon surrounded by islands that offer protection from most summertime winds, though the openness of passes means I would not want to be here if the wind increased from the north. It is Labor Day weekend, our weather is perfect, and by getting here early we have secured the prime anchorage in a tiny notch. The occasional boat passing by slows down, decides we haven’t left enough room for two boats, and passes on. Several families tried to homestead here a long time ago but gave up, and now it is a Maine Coast Heritage Trust island with well-marked trails that end in untended wilds, providing plenty of exciting exploration of the forest and occasional views of fleets of holiday boats sailing in the various passes and anchored at other islands.

After leaving Wreck Island we head back to Deer Isle, anchoring on its west side under gray skies. The wind was predicted to swing around to the west and this looked like our best bet for protection, which seems contradictory since Northwest Harbor opens to the northwest. But we are well up inside, and the wind shift that occurred overnight hardly made itself felt in this peaceful bay. The day before I rowed to its head, where a huddle of historic-looking buildings marks the town of Deer Isle. Though connected by a bridge to the mainland, in recent history it still functioned as a separate island entity with a store. But sadly, like many other coastal towns, this place has lost its center.

Since it doesn’t look like we have to leave in a hurry, I pull on jeans and a sweatshirt and gather my coffee-making supplies from the locker behind the stove. Usually while the water boils the sun is climbing and turning yellow, then white, but today the light stays evenly low. It is warm enough for me to set my mug on the cockpit table, where I will plan the day’s sail up to Eggemoggin Reach, which runs between Little Deer Isle and the mainland.

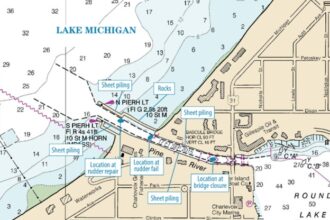

This part of the Maine coast is a patchwork of rivers, bays, peninsulas, and islands. An offshore passage misses 90% of the coast, but an inshore route takes advantage of various channels that cut through island groups. Even with small-scale paper charts it’s difficult to get an overall lay of the land. On a typical summer day with southwest winds, a sailboat can reach either way in Eggemoggin. Today, an unusual northeast wind allows us to reach, though the wind is light and puffy. Fog makes the trip challenging and cuts down on boat traffic; we only pass four boats and can wander on the changeable winds.

We spend two nights in 10-mile-long Eggemoggin Reach. There’s an art to choosing destinations that are not too far apart for the predicted wind and knowing when to leave to allow for the maximum amount of sailing, rather than motoring to the next destination. In coastal waters, this often means compromising between my instinct to leave early for the most daylight time, and the fact that winds near shore often don’t come in until late morning.

Our first night, in landlocked Benjamin River 4 straight-line miles from Northwest Harbor and nearly 15 as we had to sail it, we can’t raise anyone to take our mooring fee. On the following afternoon, within sight of our exit from Eggemoggin, we anchor in the lovely wide cove off the WoodenBoat School at Brooklin, the very tip of Blue Hill Peninsula. This is one of the few anchorages we have visited from ashore on a winter day, which provides contrast with the bright sunshine and clouds of small wooden boats learning to tack around us.

When we go ashore, the grounds are alive with groups of people. We gather ripe apples from old trees that line the walks and talk to the new manager of the school, where the first crop of hopeful boatbuilders since the pandemic started is on-site. We then walk several miles to a reportedly good food store that turns out to sell no fresh food, only canned goods with nice coffee to go. This is a disappointment. Fresh food reprovisioning is always a goal in cruising, and we have already been thwarted in several of these peninsular towns where the residents have cars and can drive to the big shops on the mainland.

Almost three weeks into our trip, it’s mid-September and the weather is forecast to turn blustery with easterly winds, making home and our mooring seem appealing. But conditions are magical in the triangular bight of shallow water formed by Black, Opechee, and Sheep islands at the base of Blue Hill Bay. We are less than a mile from Casco Passage, a tortuous path between rocks and banks that funnels all boats taking the inshore route from Mount Desert Island to the Deer Island Thorofare, but at anchor we could almost be back in the South Pacific.

We threaded this passage under sail going west 10 days ago, which means we have completed a circumnavigation of Deer Isle. Though ultimately we spend three weeks aboard on this trip, our furthest distance from home as the crow flies is barely 30 miles. This geography of closeness well defines the intimate nature of our cruise.

The sun is coming up later now, and I try to decipher from the angle of the golden patch above my head which way we are facing, but I can’t. I slide onto the cabin sole, which seems to be even colder than before. As I reach for the coffee supplies, I feel a stab of nostalgia for what has been overall a glorious cruise. I arrange the mugs, spoons, sugar, and small bottle of whole milk on a plate behind fiddles on the pulldown saloon table. I carefully measure out the drinking water, and when the coffee is ready, take it to the cockpit. The light is hazy, as if promising a mid-summer day. I do my tai chi standing meditation behind the steering wheel, facing the pass and Black Island. A lobster boat rumbles loudly as it picks up pots, and it’s hard to tell whether it’s nearby or far away. I recall an afternoon as a sailing instructor when I lay in the V-berth of a J-44 outside Camden, Maine, the saloon behind me filled with women who were excited to be out for a week learning to cruise. As I lay looking at the headliner, I thought, “This is it. If I never do anything else in life, it will be enough.” I have that same sense of profound rightness with the world as I savor my now-cooling coffee in Ora Kali’s cockpit. Then Tom makes a happy noise as he stretches in Ora Kali’s bunk, breaking into my solitary ruminations. Life on the boat comes crashing back; I still have to plan the day. And I am so happy to be here.

Ann Hoffner has been a sailor since she was 9 years old. For the last 20 years she’s written about her adventures for a variety of sailing magazines. Along with Tom Bailey, her husband and a photographer, she downsized from their offshore passagemaking P-44, Oddly Enough, to Ora Kali, a nimble, shoal-draft Sabre 30 that is teaching them the joys of Maine coastal cruising.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com