When life gives long-held racing plans lemons, you make cruising lemonade.

In late 2017, I decided that it would be really neat to enter the Marion-Bermuda Race and navigate my good old boat using good old navigational techniques (i.e., celestial) to get there.

The 645-nautical-mile cruising race from Marion, Massachusetts, to Bermuda happens every other year, and unlike some of its counterparts, it’s for amateur sailors—no professionals—and encourages a diverse fleet of boats to enter. While participants can use electronic navigation, they can also choose to navigate solely by the stars, earning some favorable handicap adjustments and extra prizes for the effort.

Tomfoolery, our 1965 Alberg 35, would fit right in, but first I needed to be sure that she was up to the task of crossing the Gulf Stream and taking on all those ocean miles. So nearly every weekend for three years, projects and upgrades consumed my sailing life. While I used to joke that everything on the boat except for the hull has been either replaced or rebuilt, after looking back on all the things that we did, the statement winds up being frighteningly accurate.

Finally, though, it was time to make it happen. Just getting to the starting line of the 2021 race would be a logistical feat, since our home port in Watkins Glen, New York, is 580 nautical miles, a canal system, a river, and a chunk of ocean away from Marion.

The Tomfoolery crew enjoys a brisk sail en route to Essex, Connecticut.

After considerable deliberation, logistics dictated we start the voyage in September 2020 so that we could be certain to arrive in Marion by Memorial Day the following spring.

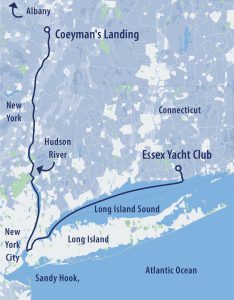

The first leg of the journey—a five-day trip through the Erie Canal—is worthy of a story in itself. The delivery crew and I enjoyed wonderful weather and an uneventful trip. Tomfoolery arrived at Coeymans (pronounced “kwee-mans”) Landing Marina, just south of Albany, New York, on the Hudson River, where she would spend the winter in storage, awaiting relaunch in spring.

By early May 2021, my crew and I were getting excited. In just five days we would be relaunching Tomfoolery and making the final 300-mile jaunt from Coeymans Landing to Marion. The Beverly Yacht Club, one of the race sponsors, would provide a mooring for us for the three weeks between our arrival and the start.

I had just finished putting together the grocery list for the delivery voyage and decided to check my email one last time before retiring for the night. There was an email from the race committee: It began, “We have made the difficult decision…”

What? I read it again. Race cancelled. This can’t be. I checked again. And again. I reached out to my contacts in Marion, and they confirmed it. There would be no Marion- Bermuda Race in 2021. The race committee cited concern for the racers’ safety after a spike in COVID-19 cases in Bermuda in March and April.

I started calling my crew members. A couple of them thought I was messing with them, but once they realized I wasn’t they were as stunned as I was. Suddenly, we were a crew without a purpose. All those months—years—of preparations, and now what?

Erie Canal delivery crew Jim McGinnis (left) and Mike Crouse (right) get ready to tuck into a home-cooked dinner while underway.

The next day, several emails arrived from other disappointed participants who were floating the idea of sailing to Bermuda as a group, despite the race’s cancellation. After all the time and effort my crew and I had spent preparing ourselves and Tomfoolery, I was giving this option serious consideration, especially since several of my crew already had airline and hotel reservations in Bermuda for their families.

While I was pondering, another email popped up, this from Bill Gunther at Essex Yacht Club in Connecticut. He had heard about our predicament through a mutual contact in Marion and asked if we would be interested in participating in the Sam Wetherill Memorial Race, a 140-nautical-mile event hosted by his club. While it might not compete with a trip to Bermuda, it did have a couple of legs that ventured into the North Atlantic to give us some time racing offshore.

I looked at the charts. We were only about 200 nautical miles from Essex—a two-day sprint down the Hudson, through New York City, then east through Long Island Sound. My crew and I kicked around the idea for a bit and decided the race would serve as a good shakedown of all the modifications we’d made to Tomfoolery over the past three-plus years. This would also help us build confidence in ourselves and our boat if we were to venture to Bermuda with others planning the trip. Decision made: We opted to compete in the Wetherill Race.

So began what we decided to call The Lemonade Cruise.

Racing to the Starting Line

When I called Bill to thank him for the invitation, I asked when the race started.

“Friday,” he replied. “But the skipper’s meeting is on Thursday evening.”

Yow! We had four days to launch, commission, provision, and get to Essex. Before we could go anywhere, I had to start studying tide tables. While I have some offshore trips under my belt, I’m primarily an inland sailor and can’t claim any significant experience with tides. One of the things I found astounding is that the Hudson River, even 125 nautical miles inland from the Atlantic Ocean, has a 5-foot tidal range, so I knew I needed to pay attention.

With our 51/2-foot draft, we could only launch around high tide in Coeymans Landing, and the marina entrance channel was also too shallow for us to pass at low tide. Timing would be critical. The marina staff said they could launch us Tuesday at the high tide around 9 a.m. If we hustled getting the boat prepped after launch, we should be able to make it out of the marina before the water got too low.

By the time the crew and I arrived at the marina Monday afternoon, Tomfoolery was already in the lift slings ready to be the first boat splashed the following morning. We spent the rest of the afternoon and evening unloading gear from the canal transit that we wouldn’t need and replacing it with provisions, race gear, luggage, and everything else we thought we’d require for an extended trip. Hundreds of pounds of stuff and countless trips up and down a 10-foot ladder later, we all slept very well on board (we dubbed the boat in the slings the largest hammock we’d ever used).

Tuesday morning dawned bright and sunny, the launch went off on time, the boat’s engine fired right up, and after filling water tanks and lashing two extra jerry cans to the deck, we cleared the shoal at the marina entrance 90 minutes later and caught a 1.5-knot favorable tidal current down the Hudson River toward New York City.

Just at dawn, the New York City skyline is outlined by early light, and the river is blissfully mirror-like with little traffic.

Big Apple, Big Tides

The lights of New York City were visible hours before we arrived. The first skyscrapers were abeam at daybreak. We were the only boat on a mirror-calm Hudson River. A consultation of the tide table suggested that we should stop somewhere and wait a few hours before venturing up East River, though Hell Gate, and into Long Island Sound.

First, we took advantage of the calm water and light traffic to pay a visit to the Statue of Liberty. We snapped some photographs as we motored by, then we popped into Liberty Landing Marina in Jersey City, New Jersey, right across the Hudson from lower Manhattan, where the dockmaster let us stay for a couple of hours and enjoy a hearty breakfast cooked on board.

Then, it was time to face Hell Gate. Three places on the East Coast of North America are notorious for their tides:

The Tappan Zee Bridge looks like modern art when lit up at night.

The Bay of Fundy, and the east and west ends of Long Island Sound, known as The Race and Hell Gate, respectively. Tomfoolery would eventually transit these last two multiple times in the coming weeks.

Currents in Hell Gate and the East River routinely hit 5 knots, making passage against the tide extremely difficult for our displacement sailboat. Coupled with the wakes and chop generated by all manner of commercial and recreational vessel traffic, the passage can be a bit of a nail-biter if you don’t hit the tides just right.

As the tide approached slack, we made one more pass by Lady Liberty for crew members who were off watch and sleeping during our early-morning visit. Then, dodging the ubiquitous New York ferries zooming up, down, and across the waterways, we headed northeast into the East River. By the time we arrived at Hell Gate, we were making more than 8.5 knots over the bottom (the current had not quite peaked in intensity), and by midafternoon, we picked up a freshening breeze and sailed eastward into Long Island Sound.

A Rude Awakening

By 1:30 a.m. on May 20—the day of the skipper’s meeting and one day before the start—we were just a few miles from Old Saybrook, Connecticut, and the mouth of the Connecticut River, where we would proceed upstream to Essex. Mike, who was at the helm, and I were beginning to consult the chart plotter more carefully to plan our landfall while the off-watch crew slept. I zoomed out the view to get a better big picture of where we were and to identify the numerous lights we were seeing.

The weather was clear, and the moon had set, so we could see a lot of buoys. We quickly identified the two or three closest lights and determined we were a little too far north to clear one of the shoals near the mouth of the Connecticut River. Locating the flashing red light marking the southern-most tip of Cornfield Shoal, I told Mike we had to go south of it, and he dutifully altered course.

A couple minutes later there was a deafening crash and Tomfoolery lurched over what was obviously a submerged rock. Crew member Katie was jolted out of her bunk, then further startled by Mike racing down the companionway, flipping on lights, and pulling up floorboards. We immediately stopped to assess damage.

With more than a little concern, Mike announced that the bilge was full of water. Our bilge is 42 inches deep and will hold hundreds of gallons of water, so this observation was significant. I watched for a moment and did not see the water rising.

“When was the last time we pumped the bilge?” I asked. At the same time my mind was racing to calculate if we were close enough to shore to run aground on a nearby beach if needed.

“I don’t know,” said Mike.

When Tomfoolery is under power, the stuffing box tends to leak a little more than it prob- ably should, so pumping the bilge is required once or twice a day during long trips. Fixing it is harder than it sounds, since we have to remove the engine exhaust system to access it.

We turned on the electric bilge pump. After a few moments, water levels began to recede, taking the tension onboard with it until…Wham! As Mike replaced the floor-boards, the keel hit rock again. How could that happen? Hadn’t we stopped?

When I reviewed our track on the chart plotter later, several things became obvious. The rock we had hit was marked on the chart, but it wasn’t visible because I had zoomed out to see light characteristics of buoys that were some distance away. The mark denoting the rock was an unlit buoy some distance south of the actual hazard it was marking. We were traveling into the current when we hit the rock, and forward momentum carried us over it, but when we stopped, the tidal current—running at a little over 2 knots—pushed us back over the same rock a second time while we were all below assessing potential damage.

After the cruise was over, Tom finally saw the nasty results of two close encounters with the submerged rock known as Hen and Chickens off the mouth of the Connecticut River.

When recounting the adventure later with local sailors, the universal response was the knowing head nod followed by tales of their own encounters with the rock known as Hen and Chickens. Apparently, striking this rock is a rite of passage, although no one we spoke with had managed to hit it twice at the same time. (Sometimes it stinks to be an overachiever. The only real damage from the encounter was the chunk taken out of the keel, which we saw months later when we hauled out for winter storage.)

Following the rather abrupt introduction to Hen and Chickens, we decided to simply stand off in deeper water to await sunrise before attempting to navigate what appeared to be a rather narrow channel up the Connecticut River. By 5 a.m. the sky was bright enough and we headed upstream, arriving at the Essex Yacht Club about an hour later. We tied up at an empty spot on the dock and grabbed a quick nap until the staff arrived to welcome us and show us to a slip that Bill (who turned out to be the rear commodore) had arranged.

During the skipper’s meeting that evening, Bill called us out as special guests who could easily claim the title of the crew that had ventured the farthest to sail in their opening race of the 2021 season. Everyone was willing to share information and advice for dealing with tides, currents, and the many local “features” that make sailing interesting and challenging.

We had made it to the start—just not of the race we’d necessarily set out to sail.

Stay tuned for Part 2 of The Lemonade Cruise in the November/December 2022 issue.