The designer of some of sailing’s most legendary boats, Bob Perry continues to push boundaries.

Issue 135: Nov/Dec 2020

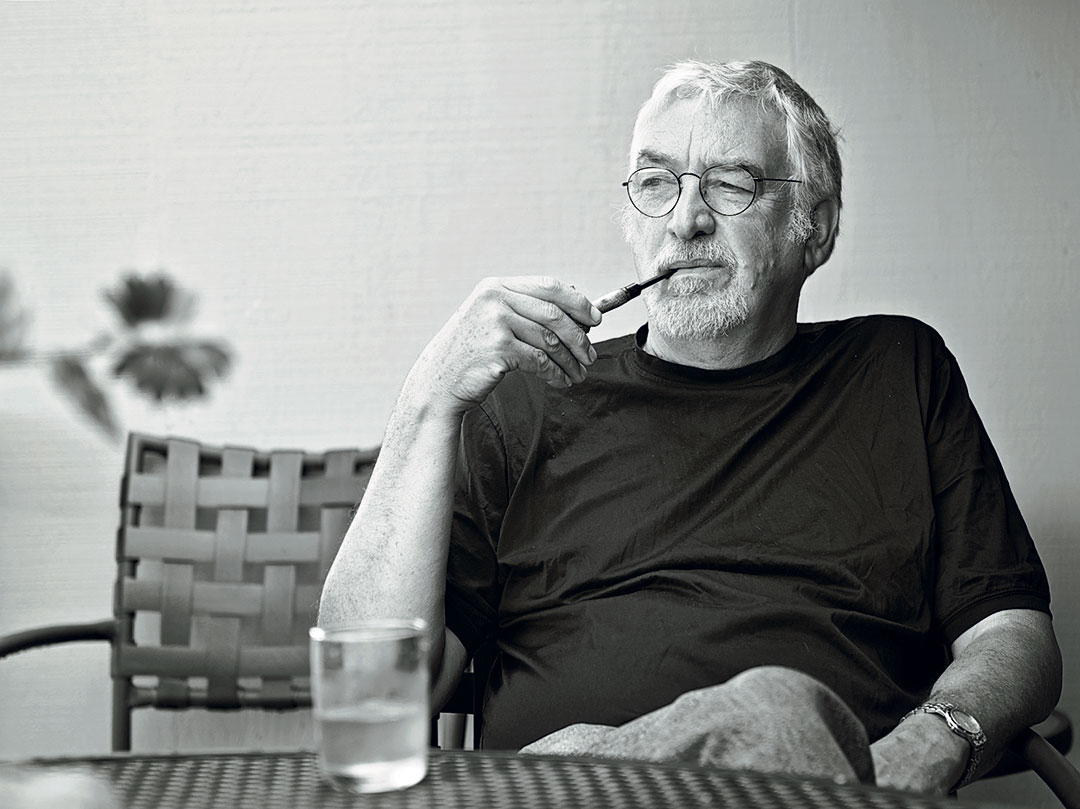

The design studio of Robert “Bob” Perry, upstairs in his Marysville, Washington, home is purposeful and busy yet warm and elegant, its walls a gallery of some of the world’s most successful and well-known cruising boat designs. Suitably awed by dozens of gleaming half-models, I ask him: Can he name them all?

“Really? You want me to tell you what all the boats are in rapid-fire succession?” he says. “Sure, sure, let’s go.

“Valiant 40, Baba 30, Tayana 37, Fairweather Mariner 38, CT 54, Islander 26, Cheoy Lee 48, Esprit 37, Meridian, Islander 34, Passport 40, Wentworth 17, Tatoosh 42, Seamaster 46, Cheoy Lee 35, Valiant 30 (which they never built, the Valiant 32 is over there), Islander 32, Mirage 26, Cheoy Lee 44, Golden Wave 42 (built by Cheoy Lee), Baba 40, Perry 47, Islander 28, CT 65, Lafitte 44…”

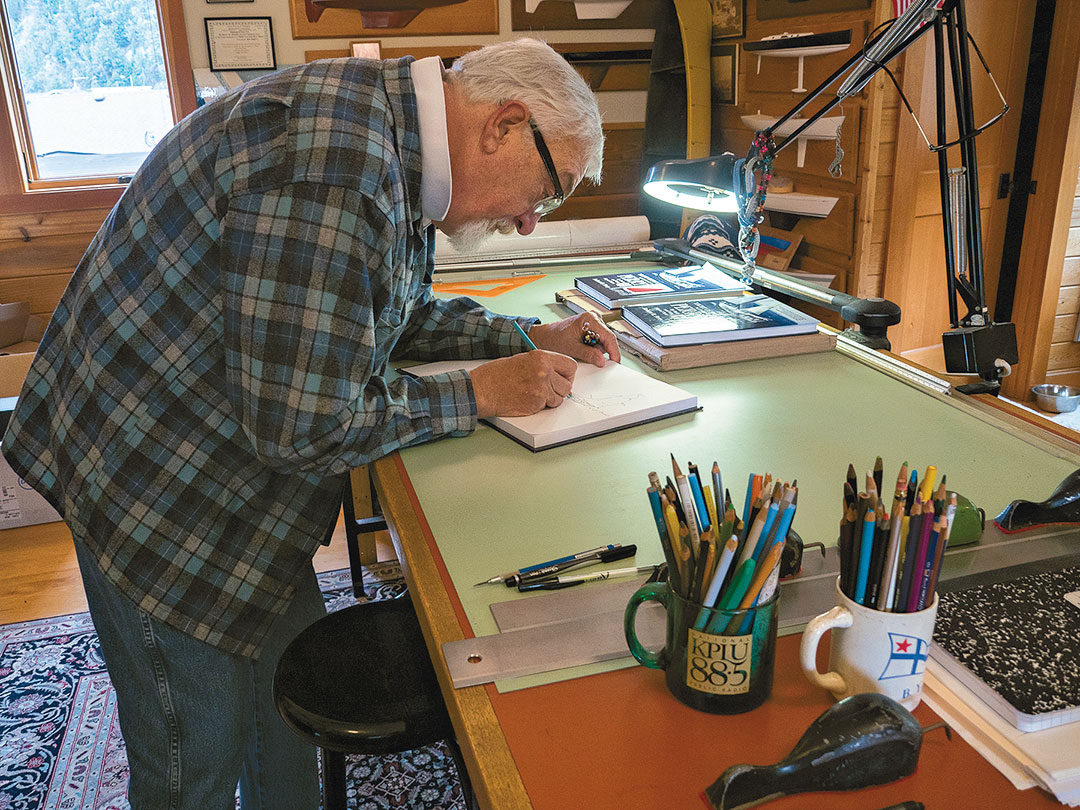

He goes on. It might be enough for another man to rest on such laurels, but everything in this studio points to the occupations of a restless, creative mind. A broad drafting table resides front and center atop an oriental rug, coffee cups stuffed with pencils of every type and color at the ready. Two acoustic guitars rest in stands near an amp, while an electric bass sits propped nearby. An Australian flag drapes over the door, an eclectic array of smoking pipes hangs on a wall, and tubes holding dozens of designs fill a rack in one corner.

A piece by Mendelssohn, the 19th-century German composer, plays softly in the background as Perry sits at his desk across from three computers and returns to his work. His right hand flutters with the mouse and he occasionally “tsks” or mutters something under his breath.

I sit awkwardly behind him, feeling something of an intruder, hesitant to break his intense focus again.

The leftmost monitor on his desk pings, piercing his concentration. It’s an update from The Robert Perry, Yacht Designer, Fan Club, a Facebook group that currently numbers over 6,400 members. Perry posts to the group most mornings. His topics vary from technical (such as offering insights into his design process) to nostalgic (perhaps reminiscing about his time building boats in Taiwan). His fans respond enthusiastically, often with questions for “the Maestro,” as he’s affectionately dubbed. Recently he’s invited them to provide input on the design of an ultimate 37-foot cruiser, a “durable, bluewater, family cruising boat design, up to today’s performance targets.”

A yacht designer engaging with fans on Facebook is something that Perry’s mentor, renowned naval architect and marine engineer William Garden (1918-2011), could scarcely have imagined. “Bill Garden had this attitude that he never wanted his photo published,” says Perry, “because, as he explained it, everyone has this idea of what a designer looks like. You don’t want to shake that image. Let them have it.”

A Love Discovered

As a youngster, Perry quite literally marched to the beat of his own drum—at one point he was kicked out of the school band for twirling cymbals overhead—an independent streak that perhaps was seeded while living his first 13 years in Australia, where his father had met his mother while on R&R during WWII.

“I got in a bit of trouble,” Perry says. “I wasn’t a troublemaker. I was just immersed in my own stuff.”

But he never got interested in boats and sailing until the eighth grade, when he chose sailing as the topic of a presentation. He became engrossed in the lore and beauty of old clipper ships, setting sail on imaginary voyages for which he kept detailed ship’s logs, dreaming of one day trying the real thing.

“I was soon buying sailing magazines and devouring them,” he writes on his website. “One afternoon I picked up a copy of Boating and on the cover was a nice photo of a Rhodes-designed Chesapeake 32. Lightning struck. I had never seen a thing designed by man that had so much beauty. I decided I would not go into the Coast Guard after all. I’d become a yacht designer.”

With the support of one of his teachers, Mr. Kibby, Perry ordered a small drawing board and drafting equipment that he could use at home. His first drawing? A model of the Civil War ironclad Merrimack. He worked part-time at a meat market to afford curves and drafting tools. Though he didn’t apply himself in more traditional topics, he excelled in Mr. Kibby’s mechanical drawing classes.

His geometry teacher, Don Miller, who was an avid sailor, encouraged him to join a local yacht club and start sailing.

“He realized I was drawing boats all the time and not doing my schoolwork…He said, ‘You should go talk to Bill Garden,’ the local famous yacht designer. I knew who Bill Garden was because I was just devouring every sailing magazine I could get my hands on.”

A nervous young Perry made arrangements to visit Garden’s office early on a Saturday morning. That day, he walked into a universe of yacht design and stood transfixed by his surroundings: stacks of designs, half models, and photos of boats. Garden took Perry out for lunch, beginning what would become a lifelong friendship.

“Looking back, Mr. Kibby, Don Miller, and Bill Garden combined to give me the skills, opportunities, and self-confidence I needed to pursue my dream,” Perry wrote in Yacht Design According to Perry.

A Budding Designer

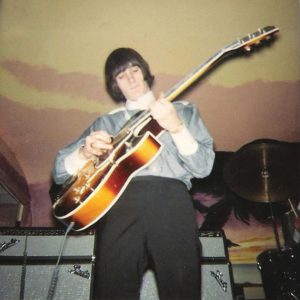

When he got to college, Perry initially studied mechanical engineering before switching two years in to become an English major. He put himself through college by playing music, having started in a band called The Bandits when he was 18.

At the end of his fourth year, he quit college and did a short stint for a company called Marine Weight Control before landing a position with yacht designer Jay Benford. Though it paid poorly, it introduced Perry to the business of yacht design.

“I was supposed to get 10 percent of every job we finished but we never finished,” says Perry. “I got $100 and a water-stained book. I still have it actually—it’s a very good book. It’s about traditional Dutch yachts.”

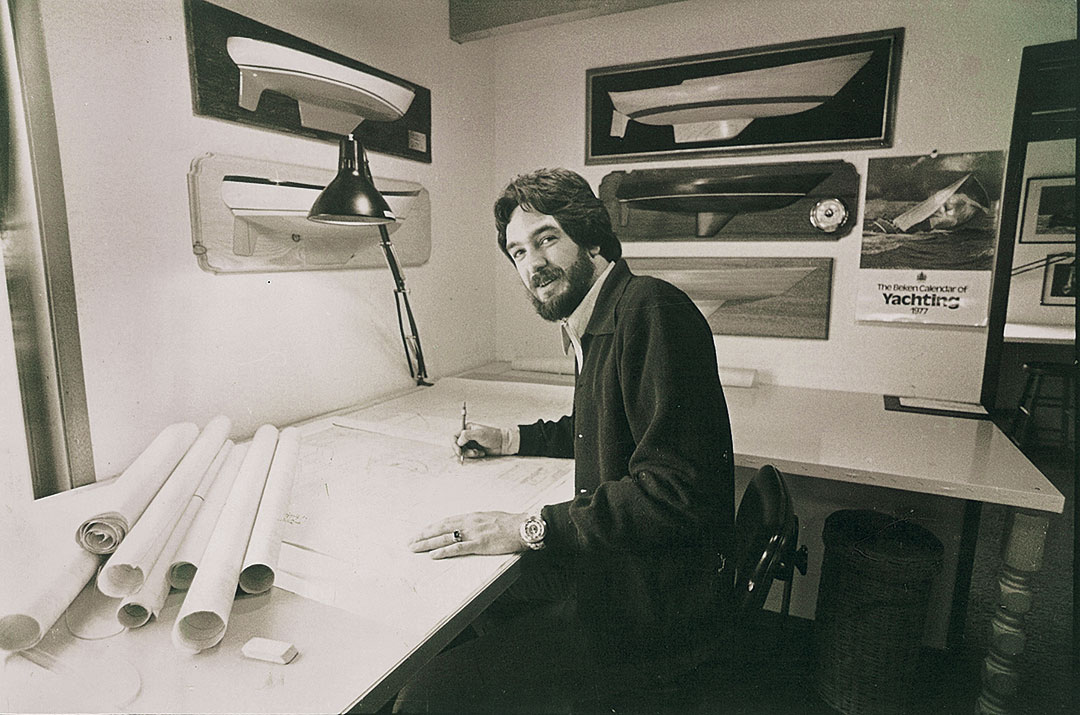

Perry left Benford’s office after a year, only to return a year later, but this time at a guaranteed hourly rate, five days a week. His first design, a 47-foot ketch, was published and reviewed in National Fisherman. Upon seeing the review, Benford insisted that all inquiries go directly to him.

Not long after, a Californian named John Edwards asked Perry to design a 47-foot ketch in a letter that Perry dutifully handed over to Benford. It sat in a stack of unanswered mail for two weeks until Perry couldn’t stand it any longer. When Benford was out of the office, he retrieved the letter and answered it.

Edwards and Perry designed the boat in his dining room. Perry also began doing drawings for boatbuilder Vic Franck. When Benford learned of Perry’s moonlighting he was “justifiably angry.”

Seeing the writing on the wall, Perry applied for and landed a draftsman position with renowned racing yacht designer Dick Carter. In 1973, he moved to Boston and began working for Carter designing IOR boats for wealthy clients.

By 1974, Perry was also working on three designs of his own, the Valiant 40, what would become the CT 54 (an evolution of Edwards’ 47-foot ketch), and the Islander 28. He was also doing drafting work for Ted Brewer at night.

“It was good old Ted who said to me, ‘You are a yacht designer.’ ’’ Perry writes on his website. “I thought if Ted thinks I am a yacht designer then I must be. Ted should know.”

The Defining Boats

Going into this interview, I knew the challenge of profiling a designer as prolific and beloved as Perry would be choosing which of his designs to focus on. I would inevitably disappoint the many Perry owners who would not see their boat in these pages. So, I unburden myself of this weighty decision and leave it to the Maestro himself.

“Which boats would you say have most defined you?” I ask.

“Well, you’d have to say the Valiant 40, and the CT 54, which was the first fiberglass boat I designed, because without those I don’t know where I’d be. And the Islander 28. My whole association with Islander gave me a river of royalties for a number of years.”

The CT 54 emerged from those first drawings with Edwards, who took them to the Ta Chaio yard in Taiwan and discovered that building the 47-footer would be cheaper than he’d expected. So, he made it bigger, creating a 54-foot clipper-bowed ketch that he dubbed the Hans Christian 54.

The young Perry labored over the designs, further refining his iconic style. He was to be paid $700 for the design, half up front and half at completion, but as time went on, the second half remained overdue. His relationship with Edwards further soured when he drew a 34-foot double ender for Edwards, never got paid, and then heard about a 36-footer being built.

“I’m thinking, ‘I didn’t design a 36-footer,’ so I called him up and he said, ‘Oh yeah, we did a bigger version.’ I said, ‘Well, I look forward to the royalties.’ He said, ‘Well, you’re not getting royalties.’ I said, ‘OK, then I don’t want anything to do with you on any level.’ So, I did the Tayana 37, which was not identical but damn close, and I sold 600. So that was my revenge.”

When C.T. Chen, the president of Ta Chaio, learned that Edwards had not paid the entire amount for the Hans Christian 54, he bought the design from Perry for the remainder of the design fee. Hence, the Hans Christian 54 became the CT 54.

Ultimately Perry developed a long and prosperous business relationship and friendship with Chen and his two brothers. Perry felt embraced by Taiwan, and he learned Mandarin and a bit of Taiwanese. The CT 54 sold well, prompting a 65-footer, then the CT 56, an update to the CT 54.

Though the Valiant 40 followed the CT 54, Perry marks it as the real start of his career as an independent yacht designer. While working at Benford’s, Perry had made fast friends with Nathan Rothman, Benford’s business manager. The two young men dreamed of starting a company together, becoming their own bosses, and building “their” boat.

Perry set to work on a 40-foot double-ender. That year, 1973, the Westsail 32 had graced the pages of Time magazine, fueling the notion that bluewater cruisers ought to be double-enders. As such, Perry wanted to create the perfect canoe stern and took inspiration from the likes of Bill Garden and Holger Danske.

His experience working with Carter had taught him a lot about performance, and he obsessively studied other designs’ sail area/displacement and displacement/length ratios after reading a Ted Brewer article about these parameters. At the time, a typical cruiser displacement/length ratio was 400; Perry’s design would have a displacement/length ratio of around 260. This was a radical departure from the traditional slow, heavy cruising mold in what would become the first performance cruiser.

The first Valiant was launched in the fall of 1974, and soon they were flying off the production line. The first builder, Uniflite, turned out 150 Valiant 40s before blistering problems with Hetron fire-retardant polyester resin helped drive the company out of business in 1984.

Valiant production then moved to Lake Texoma, where Texas Valiant dealer Rich Worstell built another 200 Valiant 40s. The Valiant 40’s success spurred several variations: the Valiant 32, 47, 50, and 39.

Perry feels lucky and proud to have his name tied to Valiant.

“I fully appreciated back in 1974 and 1975 that what we were doing with the Valiant 40 was like catching lightning in a bottle,” he wrote in his book.

His relationship with Islander began after meeting the company’s executives at the 1973 Long Beach Boat Show and then drawing the Islander 28. It became a huge success and led to an Islander 32, which also sold over 500 boats. He followed this with the Freeport 36.

Perry worked for Islander for 10 years and considers it critical to establishing him in his early career. He recalls at one point standing on the Islander shop floor, and almost every boat under construction was one of his designs.

The Ultimate Treasure

The fan page emits another ping, and we both look over to see the latest update.

“It’s pretty active,” says Perry.

“How many members do you have now?” I ask.

“Let’s see, 5,311. My wife was the 5,000th. One day she looked over my shoulder, and I said, ‘I need one more member to get to 5,000, and she said, ‘Well, I’ll do it.’ ”

Perry met his wife, Jill, in a restaurant across the street from his office in Seattle, Washington, where she worked as a server and he was a frequent lunch patron. One day, Perry asked her out sailing and she agreed. “It wasn’t my boat, but I took her out on a Valiant 40,” says Perry. “Then we went to see the movie Jaws. I got a bloody nose, then came out of the theater and forgot where I parked my car.”

Though the first date didn’t go exactly as planned, the two instantly connected. They were together a year when they had their first son, Max.

Perry points to a photo on his desk of a smiling boy and a sailboat. “That’s Spike,” he says. Their youngest son, a talented engineer, sailor, and craftsman, died suddenly from bacterial pneumonia at age 30.

“For my wife, Jill, and me, the family means everything,” Perry notes on his website. “Our two boys, Max and Spike, are the ultimate treasures of our lives…Like it or not, and I don’t like it, Spike’s death partially defines who I am.”

Though I was a bit nervous at the interview’s outset—and Perry acknowledges on his website that some people have dubbed him an occasional curmudgeon—any hint of tetchiness vanishes as we linger over family photos and the smiling faces of his grandchildren, 8-year-old Violet and 6-year-old Drake, whom Perry clearly delights in.

Perry’s current and recent work—mostly custom—includes some spectacular and creative projects like the Duffy 22, a production electric boat, and a submarine for Paul Allen, co-founder of Microsoft. His latest project is an 85-foot boat commissioned for humanitarian missions in the Philippines. The 62-foot double-ender Frances Lee—an “old man’s daysailer” designed for a friend—is a whetted knife through the water; he says it’s his favorite design.

“It’s interesting, now that I’m 73, I look at the modern boats and I think, ‘If I was 15 today, looking at those boats, would I want to be a yacht designer?’ Probably not. Because when I was 15 and 16, there was tremendous diversity, and now there’s tremendous sameness and orthodoxy. I realize that I’m not going to move with the times. I’m not going to follow the trend. I want to do boats that I want to do,” he says. “If you asked me to design a French boat, I’d say, “Get some French guy, that’s not my style.” My heart wouldn’t be in it. I didn’t realize I had a style before, but I know now I do. I’m a Pacific Northwest guy.”

I ask him what advice he would give to someone starting out.

“God, there’s so few opportunities to get started,” he says. “With my career, you really have to chalk it up to the fact that I was in the right place at the right time.” Perry now mentors a budding designer in Australia, whose father contacted Perry when the boy was just 8, saying he wanted to be a designer.

“He’s about 16 now, and he started designing and building his own boats with very little parental help. I’ve always felt that it was a bit of an obligation to give back, because Bill Garden took the time to talk to me.”

Perry’s dog, Ruby, comes running in looking for a rub, and Perry happily obliges. As our interview comes to a close, the conversation turns to pets and the stray cat that Perry feeds every day.

Somewhat sheepishly, I ask him if he’ll sign his book for me. He opens it on the drafting table. Rather than inscribe the front page, he takes a handful of colored pencils and carefully illustrates a beautiful schooner, beam reaching across the inside page. My very own Perry design. He signs his drawing with a flourish. Then, the Maestro closes the book.

Perry-phernalia

Every year, Perry owners congregate in late August at Port Ludlow, Washington. Activities include potlucks, a surprise guest speaker, and live bands. (Though Perry no longer plays music regularly in a band, he’s been known, on occasion, to play at the annual Perry Rendezvous.) The event fills up quickly so be sure to reserve a spot. See perryboat.com for more information.

For owners of Perry boats not mentioned above, as well as anyone interested in the background of some of the best-known good old boats, I emphatically recommend Perry’s book Yacht Design According to Perry. He explains several aspects of yacht design and tells the fascinating stories behind his boats.

Fiona McGlynn, a Good Old Boat contributing editor, cruised from Canada to Australia on a 35-foot boat with her husband, Robin. Fiona lives north of 59 degrees and runs WaterborneMag.com, a site dedicated to millennial sailing culture.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com