Builder of the Seawind and other legends

The Allied Boat Company established its building site on Catskill Creek in Catskill, N.Y., 100 miles north of New York City. Just off the Hudson River, it was an ideal place from which to build and launch boats. For the company’s entire time in business, from 1962 to 1981, it remained at this location.

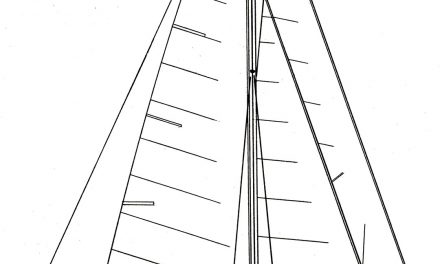

The seed for the Allied Boat Company was planted in February of 1960 when Annapolis naval architect Thomas Gillmer designed a 30-foot ketch- rigged sailboat for Rex Kaiser, an attorney from Wilmington, Del. This boat would become the famous Seawind 30, the first fiberglass boat to sail around the world with a voyage beginning in 1964. Alan Eddy spent four and a half years circumnavigating the globe with Apogee, hull #1.

Lunn Laminates of Port Washington on Long Island Sound created the molds for this boat and built five of them. It’s not clear how Lunn Laminates and the original group that was to form the Allied Boat Company were introduced. Perhaps Lunn Laminates sought sales help from the New York City firm Northrop & Johnson, due to their reputation as the most successful yacht brokerage firm on the East Coast.

Northrop & Johnson enlisted the aid of Thor Ramsing of Greenwich, Conn. Ramsing, in addition to being a well-known racing sailor, also had the financial resources necessary to initiate a new boat production company.

Allied’s treasurer, Serge McKhann, filed papers with the states of Delaware and New York on Feb. 9, 1962, officially establishing the new company as Allied Boat Company, Inc.

The company was formed with $70,000 in cash contributed by Ramsing, $31,000 worth of molds contributed by Lunn Laminates, and $31,000 worth of designs and specifications contributed by Northrop & Johnson. The company ownership was based on 96 shares of stock with Ramsing holding 83 of these. The remaining 13 shares were divided evenly among James Northrup, George Johnson, and Howard Foster.

Foster, a marine consultant and representative for Northrop & Johnson, was named president. They agreed to establish the building site in Catskill, N.Y., in what was originally a brick plant. Located on the Catskill Creek just off the Hudson River about 100 miles north of New York City, it was an ideal place from which to build and launch their boats.

Ramsing did well racing his Seawind, winning prizes in the Southern Ocean Racing Circuit. The Allied reputation grew accordingly, but he was not complacent enough to produce just one type of sailboat. From the beginning, Allied needed other models from notable architects in order to please larger families and deeper pocketbooks.

Ramsing also had been very successful racing his 46-foot Solution designed by Sparkman & Stephens. He reasoned that a smaller version of the same boat might be readily accepted. He asked Frank MacLear and Bob Harris to design the smaller boat. They created the 35-foot Seabreeze, a centerboard boat which could be rigged as a sloop or yawl. The company built 135 of these over a nine-year period beginning in 1963.

A short while later another well- known naval architect, Bill Luders, introduced the Luders 33, the third exceptional yacht to grace the Allied yard. Next, Allied added the Britton Chance-designed Chance 30. With its fin keel and spade rudder, it was a bit ahead of its time and not received as well as the other “sturdier hull” models.

In 1964, only a year after forming the company, Ramsing sold his share of the partnership to Northam Warren, another well- known racing sailor. Warren also purchased the stock held by Lunn, Northrup, and Johnson, making him the primary owner of the Allied Boat Company. During the remainder of the ’60s, Warren and Foster aggressively marketed the four models in the Allied line of sailboats.

Foster maintained control of production and sales at the factory while Warren went “on the road” attending boat shows and entering races with his Seawind 30. The company sold their products directly to customers; there were no distributors.

Northam Warren was the key leader during the company’s best years.

Northam Warren

Northam Warren had a great perception and zeal for life. He was raised on Long Island, where his father, an avid sailor, saw to it that his children, including two daughters, each had a sailboat. The senior Warren raced centerboard boats when he wasn’t attending to the family cosmetic business. Northam attended Princeton University and won major sailboat races three out of his four years there.

After service in the field artillery in World War II, Warren owned several boats and traveled extensively to race them. Some of the races included the Annapolis to Newport Race, the Bermuda Race three times, the Chicago-to- Mackinac Race, and two Transpacs to Hawaii.

During my interview with Northam Warren, I learned that Allied became the first company to supply fiberglass hulls in colors other than white. This was an exclusive option, which actually started with the Seawind 30, but was also available with their other models. The company’s aggressive marketing strategies often gave it a jump on competition. “She’ll cross an ocean if you will” was the oft- repeated motto associated with the Seawind 30.

Warren noted that another clever promotion was the annual Pinkletink, named after a frog which lives in a tree on Martha’s Vineyard. Each year he had the factory do a special fitting job using all the latest and heaviest hardware. These boats were exceptional, sporting the latest in sails and the most sophisticated equipment on the market. Every part of the boat was “ultra- finished.”

At the beginning of each season, Warren went racing with the Pinkletink. Well-known in the circuit and a crafty racing skipper, Warren, with this highly prized Seawind became a familiar figure from New England to the Caribbean. Anxious admirers knew this special boat would be for sale at the end of the season. After three years, many people were waiting to purchase these special Allied boats.

Glen Neal

While Warren was promoting Allied products north and south via boat shows and racing circuits, Howard Foster and the factory had the responsibility of building boats to fill the orders he was creating. A primary member of the factory team was foreman Glen Neal, who was born and raised in Catskill. He was looking for work in 1966 to fill in the winter months that usually crippled his carpentry business. His timing was good. The Allied Boat Company, going strong at that time, had plenty of orders gathered from summer and fall boat shows and racing events.

Neal went to work for $1.50 an hour. He planned to stay there through the winter, then start building houses again in the spring. He didn’t know or particularly care about boats, but it was a warm indoor job during the winter.

He immediately recognized the inefficiency of having too few pieces of equipment for use by too many employees. His department had only one electric hand drill and one sabre saw, for example. In order to retrieve these small power tools, workers made numerous trips to other parts of the shop, which wasted time and frustrated workers. After six months Neal presented Foster with his ideas for production improvements and was rewarded with a promotion to foreman of the carpentry and finishing department. He stayed with Allied from 1966 to 1972, during what appear to have been their most productive years.

According to Neal, Allied was recognized as a high-quality boatbuilder — possibly the third best in the world. I was unable to learn what companies the two other leaders were, but the integrity of Neal’s interview lends credibility to this statement. Readers may speculate about the other two.

Neal ultimately led a crew of 35 who did carpentry work inside and outside: deckwork, handrails, bowsprit, and bulkheads along with some minor fiberglassing. A separate department did hull and deck fiberglass work. A third department did the wiring and electrical installations. The building process was synchronized, using a progress board and a card system to track projects as work moved each boat along the assembly line. Neal and his team added the finishing touches as the boats moved out the door.

Thanks to the efficiency in the plant, few boats were returned for rework. Allied could afford to give the owner a strong warranty. Neal occasionally went out on calls to deal with minor problems, like a blister on a wood bulkhead.

Neal said he prided himself on doing things right and that the Allied Boat Company was a good place to work. Peak employment reached about 130, and orders were plentiful during the late ’60s and early ’70s.

Neal suggested that quality workers should receive top wages. He recommended to management that they offer a pension plan or an incentive program to help inspire employee output. He kept records of the trimming crew’s performance and introduced competition to improve the quality of work. He was obviously a strong catalyst in the development of the Allied work- force and in the solid reputation which the company earned as a result.

Times change

Over time, other models were introduced. The Greenwich 24, by George Stadel, was the smallest boat offered by Allied. Not as popular as the other heavier models, the molds were eventually sold off to Cape Dory and ultimately became the Cape Dory 25. The fleet was expanded to a 39-footer and the ultimate XL-2, a 42-foot sailboat designed by Sparkman & Stephens. Orders were plentiful, giving the appearance that all was going smoothly.

Early 1969 brought changes which would eventually make Allied flinch and ultimately cause it to falter. Oil prices would soon escalate from $5 to $20 per barrel. Because it is a principal ingredient in fiberglass, the steep price increase in petroleum caused a substantial rise in production costs.

In addition there were some leadership problems and personality conflicts in the front office, which introduced chaos in the company and caused many to leave. Assistant plant manager Bob Jones departed in 1969, closely followed by plant manager Walter Laskowski. The loss of these key managers in the production area negatively affected employee morale.

The unsettled mood reached throughout the administrative, engineering, and labor departments. Together with negative national and international economic influences, the strains on Allied were taking a toll. Eventually, officers filed a mortgage foreclosure at the Greene County Courthouse on March 18, 1969. This notice signaled trouble in the front office at a time when the cash flow from orders should have been adequate to keep the company afloat. During this time increasing numbers of suppliers began to file judgments against the company. Some information suggests that Warren bought Foster’s interest in 1971, thus making him the sole owner of Allied.

The period from 1969 to 1974 must have seen some very traumatic moments. Employees who were experienced and capable were leaving for other employment. Recognizing this downward spiral, Warren placed an ad in The Wall Street Journal in 1973 to sell the company, 11 years after it was formed.

Saved?

At this point, a shining star appeared for the company. Robert Wright, a cruising sailor from Little Falls, N.Y., put together a partnership with two others and negotiated with banks and creditors to allow him to start building again. Wright was an electrical engineer, had obtained a law degree from Cornell University, and was experienced as a practicing attorney.

He and his partners put up $200,000. That infusion of cash, together with the backlog of orders equal to six months’ production and deposits of $177,000, made the future look brighter for the new company, now called The Wright Yacht Company. Wright’s wife, Jean, was secretary, and their son, Paul, was plant manager. These three knew the meaning of work and the importance of customer satisfaction.

During this time, Wright commissioned Thomas Gillmer to create another legendary Seawind, slightly larger than the original. This became the Seawind II. A ketch-rigged 32-footer, it had the same hull as the previous Seawind. The Seawind II served as the flag- ship of the new company. Other new boats included the Princess 36, Mistress 39, and the Mistress Mark III. This nucleus of quality yachts promised to put Allied back on course as a front-runner in American boatbuilding. The promise, unfortunately, was unfulfilled.

Anxiety, possibly induced by stock market fluctuations and an unsettled economy, caused Wright’s partners to retreat, taking their financial support with them. This left the firm in severe financial distress. Bills began to mount and liens against the company started appearing. Operations must have been fairly normal until the third year of their lease, since the first lien was not filed until July 1978.

The Wright Yacht Company was closed and the Job Development Authority (JDA) became holder and full owner of all Allied equipment, fixtures, molds, and real estate. The future appeared to offer little promise of salvaging what was once a successful boatbuilding enterprise.

Fortunately, the JDA located Stuart Miller, an attorney from New York City, who owned an Allied Princess. He was familiar with the company’s reputation and apparently convinced the JDA he could save jobs for Greene County and make the business profitable once more. He also planned, coincidentally, to build a 50-foot sailboat for himself.

With Miller as the new CEO, another name change was introduced: CFG/Allied. I was unable to locate the meaning of these initials until Ed Hodgens, a faithful 15-year Allied employee, explained that they had stood for Conception for Financial Growth.

Miller assumed control of the company in early 1979. A report in a Seawind II newsletter claimed the 100th Seawind II was completed and delivered to Florida around the same time.

Articles in boating magazines tracked mistakes of CFG/Allied and reported attempts to rescue the company. One magazine was candid, placing blame on the company leaders for “not being familiar with special problems of building and marketing boats.” The doors of this third generation of the Allied Boat Company were closed in April 1980.

Closing chapter

Once again, the JDA was on the hunt for a buyer. They found a man with a working knowledge of marketing sailboats. Brax Freeman, a former yacht dealer, boasted of entrepreneurial skills. He promised to move the “new” firm, now to be named International Cruising Yachts, into a place of prominence in the boating world.

Freeman, according to employees, had a flair for entertainment and gave prospective buyers dinner and show tickets for evenings in New York City. These enticements were meant to lead to the purchase of one of ICY’s sailboats. Freeman’s tenure with ICY lasted until late 1981, when he collapsed under the financial pressures brought to bear by angry creditors and unpaid tax collectors. The closing chapter of this fine old boatbuilding company was being written.

Various letters from JDA seeking buyers for the land (5.05 acres) and equipment indicate their persistent efforts to recoup money lost during their many attempts to save jobs for Greene County.

Ultimately, the land was sold for approximately $200,000, buildings were torn down, and an overcrowded complex of condos, each with a boat slip included, was constructed on the water’s edge. (This venture, too, has since met with a number of obstacles.) An auction took place June 20, 1984, at which time all remaining equip- ment and molds were sold for $40,000.

Thus, it was done — the Allied Boat Company was no more.