… and Two More Transitional Racer/Cruisers

Issue 140: Sept/Oct 2021

The Redline 41 Condor’s win at the 1972 Southern Ocean Racing Conference (SORC) was no mean feat for a Great Lakes boat originally designed to the CCA rule, which the new IOR rule had superseded just two years earlier. As noted in Andy Cross’ review, Condor’s victory emulated that of her progenitor, Red Jacket, who won the event in 1968 and prompted the launch of C&C Yachts in 1969. Interestingly, Red Jacket also competed in the 1972 SORC under new ownership, finishing 7th in class and 31st overall. In fact, six of the 10 boats in Condor’s class were C&C designs, and C&C designs won three of the five divisions, as well as Condor winning overall.

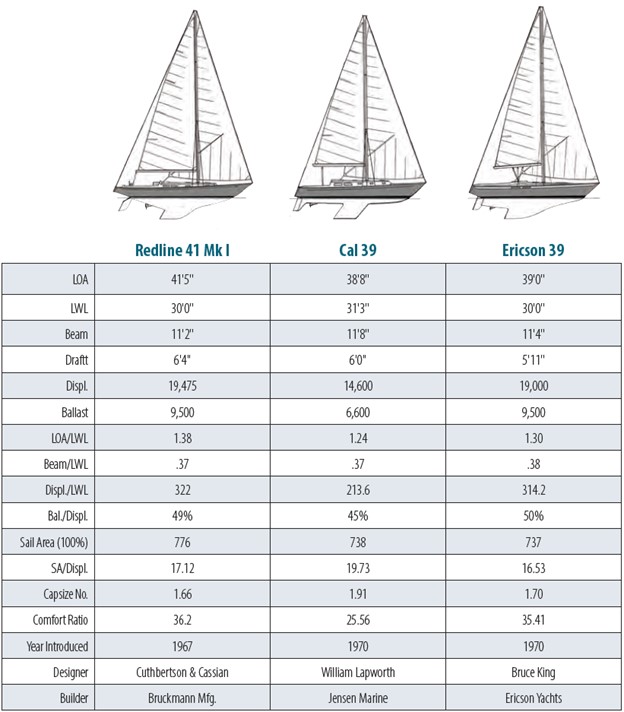

In choosing boats to compare to the Redline 41, it is logical to look at those that finished 2nd and 3rd in her division in the 1972 SORC, namely the Cal 39 and the Ericson 39. Both are 1970 designs and reflect the early influence of the IOR rule introduced that year. This is most noticeable in the striking diamond-shaped planform of the Ericson with pronounced pinched ends. In the Cal, it is visible in the flat bottom profile, a design feature pioneered by Dick Carter, one of the IOR’s authors.

In choosing boats to compare to the Redline 41, it is logical to look at those that finished 2nd and 3rd in her division in the 1972 SORC, namely the Cal 39 and the Ericson 39. Both are 1970 designs and reflect the early influence of the IOR rule introduced that year. This is most noticeable in the striking diamond-shaped planform of the Ericson with pronounced pinched ends. In the Cal, it is visible in the flat bottom profile, a design feature pioneered by Dick Carter, one of the IOR’s authors.

All three sport separate keels and rudders, firmly established at this time, although the Redline is the only one of the three with an all-movable, cantilevered, spade rudder. The Cal incorporates a small leading-edge skeg that was becoming popular at the time, and the Ericson has an elongated skeg that flows from the keel, with a partially balanced rudder. Perhaps Bruce King felt that the rating advantage in manipulating the aft girth stations outweighed the obvious increase in wetted surface created by this configuration. Or perhaps he was sacrificing maneuverability for a hoped-for improvement in directional stability.

All three boats have masthead rigs with in-plane double spreaders and double lower shrouds. However, the Ericson and the Cal hint at the coming transition to larger headsails and smaller, higher-aspect-ratio ribbon mainsails.

This transition between CCA and IOR is also reflected somewhat in the amount of fore and aft overhang, as well as an increase in freeboard. The length overall/length waterline ratio indicates that the Redline has the largest overhangs at 1.38, and the Ericson less at 1.3. The Cal is much more truncated at 1.24. The increase in freeboard, which influences girth measurements, is shown most prominently in the Ericson’s flush deck configuration.

Apart from this, the similarity in the numbers between the Redline 41 and the 3rd-place Ericson 39 are quite remarkable. Both are 30 feet on the waterline, both are about 19,000 pounds displacement with 9,500 pounds of ballast, and both have similar sail areas, although the Redline has tad more. All of this results in similar displacement/length waterline ratios of very conservative 322 and 314 respectively, and sail area/displacement ratios of 17.1 and 16.5. The Cal 39, however, is a completely different kettle of fish, being over a foot longer on the waterline and about 5,000 pounds lighter, with about the same sail area as the other two boats. This yields a much more competitive displacement/length waterline ratio of 214 and a sail area/displacement ratio of a remarkable 19.7. With these numbers, she should be a downwind and light-air flyer, which certainly was the reputation of the early Cals, starting with the 40.

Beams are also consistent between the three boats, only varying from 11 feet 2 inches to 11 feet 8 inches, with beam/length waterline ratios at about .37, indicating relatively narrow boats. This is reflected in the capsize numbers, all under the threshold of 2, with the lighter displacement of the Cal pushing hers to 1.9 compared to about 1.7 for the others. Comfort numbers also follow the range in displacements, with the Redline and Ericson almost equal at about 35 compared to the lighter-displacement Cal at a lively 25.

The year 1972 would be the high-water mark for C&C designs at the SORC. In 1973, Doug Peterson would launch his One Tonner Gambare (also influenced by Dick Carter), and all these later CCA and transitional IOR designs by production builders would fall victim to newer, often custom designs that were better at exploiting the proclivities of the new rule.

It is gratifying to see people devoting the time, money, and energy to upgrade classics like Condor to preserve them for future generations, and her current owners are to be commended for preserving this legendary piece of sailing history. The Redline, Ericson, and Cal each embody a person¬ality tied to a remarkable period in yacht design when more and more people from all walks of life embraced offshore racing, be it on bays, lakes, or oceans. This was a period of great democratization of the sport, when a family like the Blacketts could come down from the Lakes on their winter cruise on Condor and win the SORC overall.

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Rob Mazza is a mechanical engineer and naval architect. He began his career in the 1960s as a yacht designer with C&C Yachts and Mark Ellis Design in Canada, and later Hunter Marine in the U.S. He also worked in sales and marketing of structural cores and bonding compounds with ATC Chemicals in Ontario, and Baltek in New Jersey.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com