Maybe you’ve found the exact boat you want and have the money to pay for it, but you don’t have the free time to bring it home. Maybe you dream of cruising far from your home port, but you have only a month’s vacation and don’t want to spend it all at sea. Or an inviting rally/race coincides with your three-week holiday but getting the boat home means a windward slog. A perfect cruise would be ruined by setting off into foul weather to cover the 1,000 miles home.

Each of these scenarios leads to considering yacht delivery by sea, truck, or ship. Sea delivery usually costs the least, but there can be hidden expenses and potential pitfalls as you search for the right skipper and create a good contract to cover both of you.

Then there is the opposite side of the coin. You dream of skippering a yacht beyond the waters you know. You love a fine passage and being at sea but are without a boat or the funds to pay for your habit. You have cut the ties with life ashore and are out cruising but find your funds running low when someone offers you a chance to deliver his boat back to the mainland. (This happened to us 31 years ago.) How do you handle this opportunity so it leads to becoming a successful delivery skipper? The first step, as the owner of the boat should know, is to accept that delivery jobs are business deals, and every business deal has two sides.

Simply put, the owner of the boat will be handing his yacht, which is almost as dear to him as his 15-year-old daughter, to a complete stranger who will take it on a journey full of potential dangers. The owner wants his boat to arrive in the same condition in which it left, as soon as possible, for the most affordable rate.

The yacht deliverer, on the other hand, sees a Pandora’s box — a boat full of hidden problems. All he wants is to move it from point A to point B as quickly as possible with no breakdowns or delays so he can collect his fee and get on with his own plans.

In few business relationships do employee and employer have less personal contact. That is why special thought should be given to the delivery contract. The owner should know what he is asking for and whom he is hiring. The deliverer must consider the responsibility he is assuming.

The owner

Deliveries cost money, and there are few bargains. When you hire someone to sail your $50,000 to $400,000 yacht across an ocean, you need a skilled person who will maintain your investment while it is underway. The person you hire must know not only how to navigate, sail, handle a crew, and operate engines and generators, but also how to repair almost everything on board with what spares are on the boat. He must know how to find supplies in foreign ports. If the delivery is not across an ocean, but along the Intracoastal Waterway or other inshore route, he must be able to cope ably with anchoring and mooring situations and maneuvering in close quarters. And he must know how to maintain, varnish, and keep your boat interior and exterior clean. This adds up to a very skilled person. Remember that your delivery captain is involved 24 hours a day from the moment he steps aboard, and you’ll understand why delivery fees look high at first glance.

At present, a contract delivery will cost you $1.75 to $2.50 a nautical mile, based on the normal sailing route for any particular voyage, plus fuel and airfare for the captain and a reasonable number of crew. Tradewind passages would be quoted on a great-circle route, allowing for the extra miles required to get down to the fair winds, not on a rhumb line between two destinations.

Some teams also charge for food and airport-to-boat taxi costs. Or you can hire a delivery captain on a daily basis for between $150 and $225 daily plus all expenses including crew costs, food, fuel, and airfares. With a good delivery team, the final fee will come out about the same whether you figure it on a contract or a daily basis.

The alternative

What is the alternative? You can move your yacht by truck for continental deliveries or by ship for transoceanic journeys. If your boat is less than 30 feet and the distance involved is more than 500 miles, the cost by truck will usually be less. But once you reach 36 feet in length or a 10-foot beam, you’ll most often pay more for trucking. Moving your boat as cargo on a ship will always be higher than delivery on its own bottom for any boat more than 36 feet in length. This is because the rate must include unstepping the mast, building the cradle, paying agents, relaunching and restepping the mast, and then transporting the boat from a big ship’s harbor to a marina. The actual shipping fee is based on the cubic area that the boat and its mast will take up. Figures vary greatly depending on port of embarkation and debarkation but two examples will give you some idea to go on.

The owners of a custom-finished Bristol Channel Cutter decided to ship their 28-footer with a reputable company for $10,000 total cost, including insurance, from Auckland, New Zealand, to San Francisco, Calif. A delivery fee for this job would have been between $11,000 and $13,000. To sail it home themselves would have taken two to four months and entailed some windward passagemaking.

Because it was being shipped, they were also able to pack many of their household belongings inside the boat. Unfortunately, the boat was offloaded at a port 40 miles from the originally scheduled docks and, during trans- shipment by truck, a careless driver hit a bridge, damaging the mast and cabin severely. Insurance claims took almost six months to be settled.

Saved wear and tear

In contrast, another friend shipped his 47-foot gold-plater from Denmark to New York at a total cost of $18,000. A sea delivery would have cost about $11,000 to $12,000. But the owner saved 6,000 miles of wear and tear on the boat and its gear. His yacht did receive some superficial damage: a scarred toerail and a dented boom.

Good professional deliverers are expensive, shipping is expensive, but bargain deliveries can cost you even more. Frank couldn’t afford a regular delivery team and gladly accepted when a friend of his said, “I’ve got two months off. I’ll take your ketch back to England for you. Just pay for my food and airfare.” Frank had cruised locally for a few weeks with this fellow and knew that his friend’s longest passage offshore had been 200 miles, but the man loved Frank’s boat.

Two months later Frank received a message. The boat had been abandoned in a tiny port 200 miles from its starting point. Its gear had been stripped off by locals. The friend had been scared to leave port after a two-day blow outside Cape Town. His crew had jumped ship. The engine had quit. In the end, it cost Frank his boat. He couldn’t leave his job in England to go repair the damages. No delivery team would go for the boat after hearing a report of its condition. So Frank ended up selling his dream boat for the price of its lead ballast keel.

Delivering a boat is not fun; it is work. Asking amateurs to do it is asking for trouble. We can cite stories of cut-rate deliveries that took two months to move a boat 800 miles, of boats abandoned during storms, of boats confiscated when non-professionals who had no reputations to protect used them for smuggling drugs. Remember, a person who is not worried about protecting his professional reputation will think first about himself and second about your boat.

References

To protect yourself and your investment, don’t hire anyone to move your yacht, by land or by sea, unless you get the names and addresses of at least two or three people whose boats he has delivered. Call these people. Ask them what condition the boat was in when it arrived. If the owner tells you his boat arrived in reasonable time and in good shape, you’ve probably found a good deliverer.

If you are arranging a delivery through an agency, insist upon knowing the exact person who will be in charge of your yacht. Call that person and get the names of people whose boats he or she has delivered. If an agency is very busy, they might let relatively inexperienced people handle jobs that seem simple. Several years ago we delivered two yachts from Miami to Puerto Rico. The first time we arrived in San Juan we noticed a beat-up 35-foot charter boat laid up at the dock, its transom black with soot, its diesel out of commission. Three weeks later we again arrived to see a second boat, identical to the first, its transom and engine in the same sad state. Both boats were part of a large contract handled by a firm with an excellent reputation. In each case the deliveries had been turned over to sailors on their first professional jobs, since the distance involved was only about 700 miles. No matter what reputation the agency has, check the references of the person who will be in charge on your boat.

Not so inexpensive

Don’t be swayed by smooth talk from a sailor walking down the dock. Check him out. The owner of a 50-foot South African yacht came by one day to tell us he’d found a very inexpensive captain, the crewman from a local charter boat who told excellent sea stories. It was only after the boat was at sea that the owner took a look at the boat owned by the man he hired. It was in terrible condition, secured on a mooring in the most exposed part of the harbor. As the owner said, “If he takes care of his own boat that way, what will mine look like in two months?”

Once you’ve located the person you will hire, tell him all the problems he may encounter on your boat so plans can be made accordingly. If there is no reliable self-steering, tell him so he can arrange sufficient crew. Tell him the state of your engine, its fuel consumption, your ground tackle, all electronics, and sails. Give the captain a frank idea, or he may fly thousands of miles and find he didn’t bring along the right gear or spares. Then he’ll have to spend your money and his time getting ready to set off.

An owner got a transatlantic call from his delivery skipper: “Sorry, I can’t take your ketch across the Atlantic until it has new standing rigging.” The owner replied, “I crossed the Atlantic with it two years ago. It’s good enough. Ignore the rust.”

The well-respected delivery captain then refused the job, the owner lost the cost of two airline tickets. A second deliverer came and said the same thing. So the rigging was replaced. If you have hired a good person, trust his or her judgment. He is the one who is risking his life and reputation when he sets off across an ocean.

Remove treasures

The delivery crew will be living on your boat for several weeks, possibly in rough conditions at sea. So if you have any treasures, either take them off the boat or store them carefully away and warn the crew. There is bound to be some wear and tear during any passage, and you must expect to lose a glass or two or have some chafed lines.

If this is a windward delivery, expect some wear and tear on your engine. Most delivery skippers must meet a schedule, so they will motorsail when they can’t lay their course. In the case of racing boats, this may actually be cheaper — a savings on the lives of your sails will more than make up for the added engine hours.

Most professional delivery skippers do not want to take owners along on the trip. Owners want to cruise, learn about navigating, and enjoy the trip. Skippers want to move the boat fast and have a crew who will take orders and do the menial work. It’s difficult to tell an owner to scrub the bilge or clean out the head. It’s harder yet to say, “We’re setting sail today,” if the owner wants a few more days in port. Taking owners on deliveries is a conflict of interest.

Be sure to inform your insurance company before the delivery captain actually takes charge of your boat. In most cases, insurers will be more impressed with good references than with professional papers or skippers’ licenses.

Finally, as in all business deals, get a contract. Make sure it gives an estimated delivery time. It should also include the expected route and number of crew the delivery captain will take, plus what expenses he will cover, and what you, as the owner, must pay for.

The deliverer

Delivery work looks like a great idea: 150 bucks a day just to enjoy yourself and go sailing. But, few delivery jobs turn out to be fun. Job equals work. People aren’t going to pay you to take a well-outfitted, fine sailing yacht on a downwind, perfect- season cruise. Boats are almost always delivered to windward. Old or neglected boats are delivered. Brand-new boats fresh from the factory full of bugs and untried systems are delivered. And whatever the conditions, the owner usually wants the boat as soon as possible. In most cases, delivery services figure on one day for every 100 miles, plus pre-departure preparation time. That doesn’t allow you much cruising time. On one of our typical long deliveries, 5,800 miles from Spain to the U.S., we spent 10 days preparing the boat, 50 days at sea, and 11 days in four ports for a total of 71 days. Two days in each port we devoted to renewing stores, going over engines, and maintaining the sails and varnish. That left us three days for relaxing in two months, or less than a day per port.

One boat we took down to Mexico a few years ago shows the general average times for a shorter delivery. We spent three days getting the boat ready for sea, eight days at sea, and one-and-a-half days in Cabo San Lucas waiting for the owner to arrange to rendezvous and accept his boat on the mainland. That worked out at 13 days for a 1,200-mile delivery.

Most delivery captains combine their work with another profession unless they are at the top of the list with a busy delivery service. Otherwise, they will have a hard time earning enough money moving yachts to support a home and family. But for cruising people like ourselves, delivering is good experience and a fine way to earn a lump sum of money because it’s hard to spend much at sea.

Great responsibility

Delivering someone else’s dream boat is a large responsibility. Instead of taking six months or a year to get to know the boat, you have to step on board, survey and assess boat and gear, outfit, provision, and get under way in a week or less. Once on board, you have to be jack-of-all-trades. You must be able to jury-rig, haywire, and maintain a boat you don’t know well, using the minimum of spares. The owner is turning the job over to you so he won’t be bothered. The last thing he wants is to be called from each port with, “the generator isn’t working” or “the pump just gave out.”

The people who make the best delivery captains are good mechanics and riggers first and sailors and navigators second.

An owner is influenced by first impressions as much as anyone. If the yacht arrives with fresh-looking varnish, scrubbed decks, and the interior in immaculate condition, he will overlook most small mechanical problems. It pays to roll up and store away carpets and curtains. In a factory-fresh boat, avoid using any facilities you can, so the owner has the thrill of stepping into a new boat when it arrives. This could earn you not only a good reference but a satisfying tip or dinner on the town.

Whatever you do, write a contract, then get a one-third to one-half deposit before you leave to pick up a yacht. Make sure your contract states the currency and method of final payment. Include an allowance for expenses during breakdowns. For example, “The deliverer will allow three days for break- downs due to faulty or worn equipment during the course of the delivery. After three days, the owner must pay an additional $100 per day to cover costs of maintaining crew and boat during time taken to repair breakdowns.” If the delivery is based on a daily fee, this is not necessary.

Ask for cash

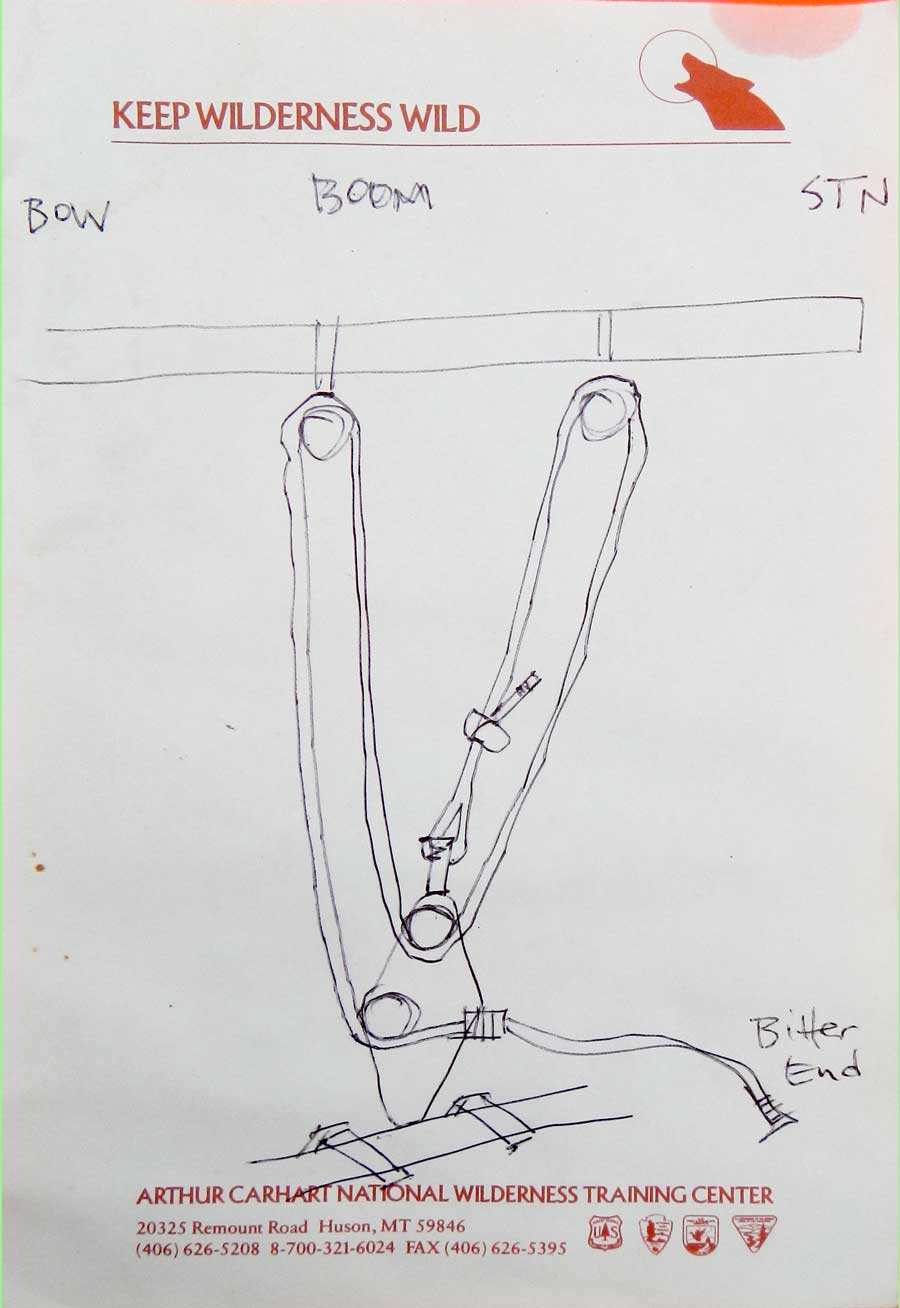

It is safest to ask for the final payment in cash before turning over the boat or its documents to the owner. We have never had any problem with payment but have heard of those who did. To protect your- self in distant ports, carry a document notarized with the owner’s signature making you captain of the yacht with full responsibility (other than transfer of ownership) during a specified time in specified waters. It may come in handy, especially in third-world countries. Keep a log for legal purposes and also to give the owner information about his yacht, the engine usage times, maintenance you did, spares you used and gear that needs attention.

Transoceanic yacht deliveries on boats 40 feet and larger are the most sought-after by skippers, but make up probably less than 10 percent of the work available. Much more common are coastal passages such as from New York to Maine, or channel crossings from Europe to England and Ireland, or inter-island transits through the Caribbean. These will often involve smaller boats and smaller sums of money. But they must be handled with the same forethought as a 6,000 mile delivery whether you are the yacht owner or delivery skipper. If you do this, a yacht delivery, just like any good business deal, can come off with both parties satisfied and ready to do business again.