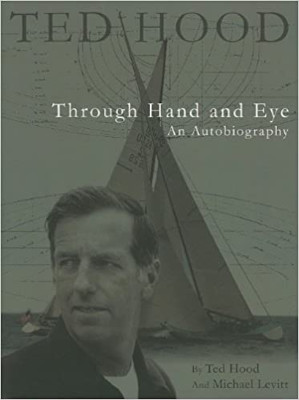

When one hears Ted Hood’s name, the first connection is quite likely to Hood Sails, the loft he founded back in the 1960s and which remains a force in that industry, though Ted has had no connection to it for many years. In fact, he has been much more than a sailmaker. Once one begins counting his many achievements, it quickly becomes evident that he’s one of the most influential sailors of all time: keen racer, including winner of the 1974 America’s Cup (aboard Courageous), equipment inventor and innovator, designer, boat builder, and of course, sailmaker.

Now 79, in 13 chapters (with lots of great old photos) he looks back over his sailing life, and not much deeper. His personal life remains just that. Still, he talks (and I say “talks” because the book is written as if he dictated the text for co-author Mike Levitt to organize and clean up) about his childhood in Danvers, Massachusetts, and the inventiveness of his grandfather and father, the latter an electrical, chemical and mechanical engineer affectionately known as “The Professor,” who later would play an important role in the development of Hood sailcloth.

By his own admission, Ted was more adept in his father’s workshop than at school. The family had boats, wood in those days, and Ted grew up not only sailing them, but repairing them as well. His father told a writer from the New Yorker this story about his son:

Once, we had to fit a new garboard plank to Shrew [an R boat]. It was a really tricky place with all kinds of curves and twists and bevels—the sort of place where an average shipwright would ruin two or three planks before he got the right fit. Ted looked at it, planed the wood, looked at it again and did some more planing. Then he put it to the hull, and it went in perfectly.

That seems to sum up much of his life in boats — always finding the perfect fit. He built his first boat at 12 and checked out Gray’s Sailmaking from the library to figure out how to make sails for it. Therein began a long and self-taught investigation into the art and science of sails. Just a junior in high school, in 1945 he enlisted in the U.S. Navy.

Afterwards, he flirted with sailmaking for a short time before making a commitment to the profession in 1950. His first “loft” was not auspicious: sewing sails in his bedroom on his grandmother’s 50-year-old Singer sewing machine. But if his worksite was unimpressive, the products of his labors were, and gradually Ted built a reputation as a first-rate sailmaker. Compressed rings and the crosscut spinnaker with wide shoulders were two of his innovations. What else soon set him apart from the competition was deciding to weave his own sailcloth. The first looms were set up in 1952 using DuPont’s recently introduced Orlon, and later Dacron (polyester). Hood sailcloth was more tightly woven than other cloths, and therefore believed to be superior. It didn’t hurt that Ted’s father, Stedman, was an expert in fiber technology.

Five chapters are devoted to Twelve Meters and the America’s Cup. Ted’s involvement included supplying sails, crewing on Vim (1958), designing and campaigning Nefertiti in 1962, and eventually skippering Courageous to victory over Australia’s Southern Cross in 1974. Whether you like racing or not, these detailed accounts of the yachts, the sails, the crews and the tactics are fascinating, as only they could be, coming from an insider.

Ted’s signature yacht design is a moderately heavy displacement hull form with generous beam for excellent form stability. A good example was the 60-foot American Promise, which in 1986 Dodge Morgan sailed solo non-stop around the world in a then-record time of 150 days. Ted built the boat as well, at his Marblehead yard.

He continues to this day designing and building boats in the U.S., Asia and Europe. It’s almost as if he can’t help himself. Early in his autobiography he notes that his parents didn’t take him sailing until he was a month old. Refusing to retire, he jokes that he’s been trying his entire life to make up for that month lost.

Ted Hood: Through Hand and Eye by Ted Hood and Michael Levitt (Mystic Seaport, 2006; 199 pages)