… and Two More Spirited Coastal Cruisers

Issue 139: July/Aug 2021

The key element driving the evolution of yacht design over the past 150 years has been the rating rule in effect at the time. Each new rule produced its own design type that designers optimized to beat that rule, and that type became the norm in yacht design for that period. For instance, it’s easy to spot an R-Boat designed to the Universal Rule, or a 6 Metre designed to the International Rule, or boats designed to the CCA and IOR rules.

But with the demise of IOR in the late 1980s, and its attempted replacement with time allowance systems based on velocity prediction programs, the rule supposedly no longer dictated design types. So, the question is, without the influence of a commonly accepted rating rule, would a popular “type” still emerge, or would the sailboat market generate a variety of new styles of yacht design?

But with the demise of IOR in the late 1980s, and its attempted replacement with time allowance systems based on velocity prediction programs, the rule supposedly no longer dictated design types. So, the question is, without the influence of a commonly accepted rating rule, would a popular “type” still emerge, or would the sailboat market generate a variety of new styles of yacht design?

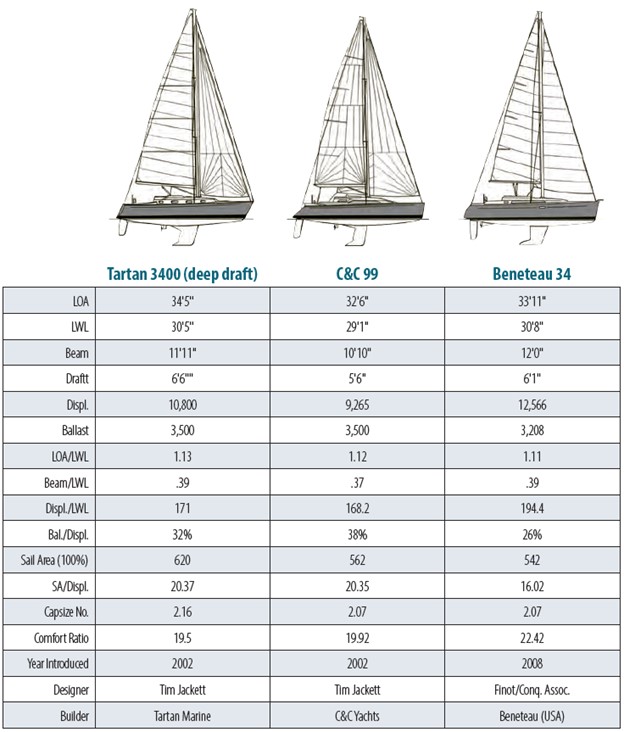

What we see as we entered the 21st century is more the former than the latter—that is, the evolution of a design type that is based on a number of shared characteristics, such as wider, more powerful aft ends that increase room in the cockpit and permit larger aft cabins, and longer waterlines to achieve greater un-penalized performance. The Tartan 3400 is an example of that trend, as are our two comparison boats, the C&C 99 and the Beneteau 34.

It is interesting that even without a rating rule, the market has evolved a distinctive type, as illustrated by these three designs, for both racing and cruising. In addition to the shared features mentioned above, each has a high-aspect-ratio vertical keel with a flared bulb, each uses an all-movable cantilevered rudder, and each sports a tall fractional sloop rig with swept spreaders, walk-through transoms, and vertical or near-vertical stems.

While the Tartan and the C&C are different brands, they share the same designer, my longtime friend Tim Jackett, and the same builder, Fairport Marine, located in Fairport Harbor, Ohio. Fairport Marine purchased the assets of C&C in 1997, specifically to add the more race-oriented C&C brand to complement the more cruising-oriented Tartan. The Beneteau represents higher volume production boatbuilding. Despite these three different market niches, all three boats are remarkably similar, reinforcing the concept of this evolved type.

Let’s start with displacements (for these and all measurements following, I’ll be using the deep draft version of the Tartan 3400). The more performance-oriented C&C, as expected, is the lightest at 9,265 pounds, the Tartan the next lightest at 10,800, and the Beneteau heaviest at 12,566 pounds. These displacement differences are reflected in the displacement/waterline length ratios of 168, 171, and 194 respectively. Compared to boats from the 1970s and ’80s, these are exceptionally performance-oriented numbers.

The lighter displacements of the Tartan and the C&C, compared to the production-oriented Beneteau, are due to the vacuum-infused technology used in laminating their hulls and decks. Indeed, the heavier hull, deck, and interior of the Beneteau is further emphasized by the fact that even with her greater weight, she has the lightest ballast of 3,208 pounds, for a very low ballast/displacement ratio of only 26 percent. She will need that 6-foot draft and 12-foot beam to stand up in a breeze, which could explain her smallest sail area of 542 square feet, compared to the Tartan at a hefty 620, and the C&C at 562. These areas result in sail area/displacement ratios of 20.3 for the Tartan and C&C, and 16 for the Beneteau. However, keep in mind that rather than an overlapping jib, the Tartan uses a tall, self-tacking blade jib.

These three boats also exhibit a market preference for coastal or inshore cruising rather than extended offshore passagemaking. This characteristic is illustrated in their comfort ratios in the high teens and low 20s, and their capsize numbers all in excess of the safe threshold of 2.

The relatively low beam/waterline length ratios in the .37 to .39 range speak less to the relative beam of the boats than they do to the stretched waterline length, which is also reflected in the low displacement/length ratios. No longer is length to be avoided as a negative impact on rating, as it was in almost all rules that existed in the 19th and 20th centuries.

One can’t help but notice that when the heavy hand of a rating rule has been lifted, the type that has emerged incorporates performance advantages often discouraged in older boats constrained by such rules. In fact, these boats, as evidenced by their remarkably low displacement/waterline length ratios and high sail area/waterline length ratios, exhibit performance parameters well in excess of their sisters from the previous century.

Each of these boats marries excellent performance with interior comfort, all wrapped in an attractive package. If these are the good old boats of the future, I don’t think we can complain.

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Rob Mazza is a mechanical engineer and naval architect. He began his career in the 1960s as a yacht designer with C&C Yachts and Mark Ellis Design in Canada, and later with Hunter Marine in the U.S. He also worked in sales and marketing of structural cores and bonding compounds with ATC Chemicals in Ontario, and Baltek in New Jersey.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com