For Canadian sailor and artist Christopher Pratt, the yacht was the art.

Issue 147: Nov/Dec 2022

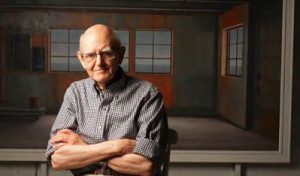

Many artists have rendered the elegance of yachts under sail, but few have captured the essence and beauty of the yacht itself as a distinct piece of sculpture, focusing on the graceful curves and shadows inherent in such a complex three-dimensional shape. No one has accomplished this as well as Canadian artist Christopher Pratt.

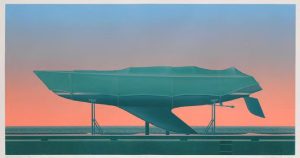

This is the boat Pratt aspired to own. About this print Pratt wrote, “I dreamt of owning a big boat, powerful and cavernous, with the damp, diesel smell that real boats have; and we are always putting to sea at night, sometimes motoring, the diesel throbbing and the boat pitching headlong into a wide rolling swell; and then we would be too close by the land, hearing the roar of water in the cliffs, the foghorn’s wailing and startled seabirds croaking harsh and alien and, rounding east and north, see the cold, blinding fire of Cape Race light.”

Undoubtedly this is because Pratt, who passed away peacefully at his Newfoundland home on June 5, 2022, at the age of 86, was an avid sailor who keenly felt the pull of the sea and imbued his work with its subtle, restless yearning. Renowned for his silkscreen prints, oil, and watercolor paintings of his beloved Newfoundland, Pratt owned several boats, almost all C&Cs. Several became inspiration and subject matter in his art.

Pratt emphasized the beauty of the whole hull in his paintings, and he often captured his subjects suspended between the two elements of air and water. Like all sailors, he seemed to be fascinated by the moment when the keel is about to kiss the surface of the sea—when she is about to make the transition to the magical interface between wind and wave.

Pratt’s C&C 43, Dry Fly. George Cuthbertson also had this print displayed in his living room.

Among his most ardent admirers was C&C’s George Cuthbertson, who had a framed Christopher Pratt serigraph print entitled “My Sixty-One” hanging in his living room, as well as a serigraph of Pratt’s C&C 43 entitled “Yacht Wintering.” Cuthbertson recognized Pratt’s emphasis on the boat out of her element, and in one correspondence between them noted, “I have been interested that you always show your subjects ‘in repose,’ static, brooding. As far as I know, ‘My Sixty-One’ is the first to have made it out of the cradle and into the water—still static—but it conveys the promise and a certain latent energy. Welcome relief from blossoming spinnakers breasting the briny!”

Pratt’s involvement with racing in Conception Bay led him to become Commodore of the Royal Newfoundland Yacht Club in 1980. “For many years beginning in the late 1970s he pursued excellence in another forum—sailboat racing,” notes his obituary (carnells.com/obituaries/ christopher-pratt/). “Although he did not at first intend to race his sailboats, he quickly grew to love the competition, the opportunity to refine and perfect his skills, and the camaraderie of fellow sailors. As with everything else, he sought perfection on the water. He made major contributions to the sport of sailing in Newfoundland and was made a lifetime member of the Royal Newfoundland Yacht Club in 2017, an award for which he was justifiably proud.”

Christopher’s son, photographer Ned Pratt, told me that over his father’s long sailing career, Christopher owned eight C&C designs, beginning with a Paceship Bluejacket 23 in the late ’60s, the C&C 30 Walrus Too in the early ’70s, followed by the C&C 35 MkI Lynxx, which he purchased with his brother, architect Philip Pratt. Philip renamed the boat Lynx and has sailed her around the world, most recently in the British Virgin Islands.

The C&C 39 Proud Mary, named in honor of his wife, artist Mary Pratt, provided the family with a summer home on the water that they sailed into ports along the coast of the island. His undisputed favorite though, was the C&C 43 Dry Fly (formerly Avanti), which he owned from 1973 to 1985.

With advancing age and scarcity of family crew, he felt obliged to sell the 43 to buy the smaller C&C 37 Cossaboom before upsizing to the semi-custom C&C 41 Greyling in the late ’80s. After selling the 41, Pratt was without a boat for a period of time, Ned said, before buying another C&C 37, Dora Maar, his last boat. He always aspired to ultimately own a C&C 61, which never happened due to the constraints of practicality.

Rob Ball has a framed copy of this print in his living room.

When I designed for C&C, I had the pleasure of sailing with Christopher aboard his C&C 43, Dry Fly, in his home waters. His advice to this Great Lakes sailor was, “Rob, in Newfoundland we treat the water like it’s sulfuric acid, so don’t fall in!”

With that number of C&C designs in his life, Christopher formed close relations with many C&C personnel and would sneak off to visit the plant in Niagara-on-the-Lake whenever he was in Toronto for a show or an opening. Indeed, Ned says that upon his return home, his father would speak of the trip to the plant and his meetings with “Big George” and other C&C people more than he would talk about the show.

John Kelly Cuthbertson, George’s son, believes that Pratt and his father shared a deep level of mutual admiration (both were members of the Royal Canadian Academy of the Arts).

All images @EstateofChristopherPratt. All reproduction images courtesy of the Mira Godard Gallery.

In correspondence, George comments to Pratt regarding “My Sixty-One,” “It hangs in our living room and is absolutely riveting. I enjoy watching visitors, many of whom have no familiarity with sailing, ships and the sea—but without ever realizing it their eyes return again and again to your haunting image—as do mine.”

Both Dan Spurr (Good Old Boat boat review editor) and I can personally attest to the accuracy of that statement and the magnetism of the image.

Ned Pratt says that even after George Cuthbertson’s retirement from C&C, his father and Big George discussed obtaining the tooling of the 43 to build another custom C&C 43 for Christopher, but by then the costs of such a project were becoming prohibitive.

With one exception, images of the serigraphs and paintings in this article were provided by Gisella Giacalone, owner and director of the Mira Godard Gallery in Toronto, which represented Pratt for over 50 years. Like me, Gisella also once sailed with Pratt, being immediately whisked away to his boat after she landed in St. John’s. Both she and Pratt were proud of the fact that she did not become seasick in the long North Atlantic swells.

Fort McAndrew. Photo by Ned Pratt.

“He was down to earth, a proud Newfoundlander and, in spite of his many accomplishments, he was never a self-promoter, always down to earth and humble,” Gisella said.

His work is featured in a great many major public, corporate, and private collections including the Art Gallery of Newfoundland and Labrador, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, the Canada Council Art Bank, Mt. Allison University, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, the National Gallery of Canada, the Rooms Provincial Art Gallery, and the Vancouver Art Gallery.

In 1980 Pratt was asked to design the new provincial flag which proudly flies today. In recognition of his extensive body of work, in 1983 Pratt became a Companion of the Order of Canada, the highest honor that can be bestowed upon a Canadian citizen, and in 2018 a recipient of the Order of Newfoundland and Labrador. He truly was a remarkable individual.

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Rob Mazza is a mechanical engineer and naval architect. He began his career in the 1960s as a yacht designer with C&C Yachts and Mark Ellis Design in Canada, and later Hunter Marine in the U.S. He also worked in sales and marketing of structural cores and bonding compounds with ATC Chemicals in Ontario and Baltek in New Jersey.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com