Delayed engine maintenance leads to a white-knuckled sail through a slice of New York history.

Issue 148: Jan/Feb 2023

“Whatever you do, retorque the head at 500 hours,” I was told by the previous owner of my Paceship 26, Pelorus.

His words came back to me one fine morning as I was leaving Eatons Neck, one of my favorite anchorages on the south shore of Long Island, on my way home after a summer cruise to Martha’s Vineyard and Block Island. Pelorus was everything I had ever wanted in a boat, with standing headroom and an inboard engine, a fine single-cylinder Yanmar YSM8 that hadn’t failed me—until then.

I’d discovered Eatons Neck, on the Gold Coast made famous by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s historical novel The Great Gatsby, after having trouble at the Sand Hole, a nearbyÁlagoonÁat the entrance to Oyster Bay Harbor on Long Island Sound. The book was set in the fictional villages of West Egg and East Egg, believed to be based on the real communities of Great Neck and Port Washington. I passed by an enormous house in Sands Point (East Egg) that might have served as the inspiration for Daisy Buchanan’s house, with “a single green light, minute and far away, that might have been the end of a dock.”

The entrance to the Sand Hole at Oyster Bay was narrow and poorly marked. I had grounded there once and heard horror stories about sunk gravel barges littering the anchorage, wrapped in anchor lines of boaters who had unhappily managed to hook into those ancient wrecks. Since then, I had been happy at Eatons Neck, home to a Coast Guard station and about 28 miles east of Manhattan. I would anchor there overnight on my way up or down the sound, since it was a convenient distance from both ends of Long Island. There were seldom more than two or three other boats sharing an anchorage large enough for dozens, and that has 10 to 12 feet of water past the well-marked entrance.

Engine Trouble

I had a quiet night in the anchorage, as usual. After breakfast I started the engine, pulled up the anchor, then put the engine in gear and edged the throttle forward. Immediately there was trouble. The engine RPMs went from a steady 2,800 to maybe 200 or less. The engine definitely didn’t sound right, and oily smoke—lots of oily smoke—was blowing from the exhaust. The engine had just enough power to get me out of Eatons Neck and out toward Long Island Sound, but it died after 15 minutes while I contemplated the parting words—“500 hours!”—of the former owner. The engine had 802 hours of running time, and I had somehow forgotten that reminder from the owner nine years earlier.

I purchased Pelorus after it had been damaged by Hurricane Bob on Block Island in 1990. A 40-footer had dragged onto it and chewed off the stem, both pulpits, and a fair amount of the starboard hull-to-deck joint. It had been a serious project boat, which I hauled to my home and rebuilt over the winter of 1990-91. Since then, I added Loran (remember Loran? Anyone?), then over time a GPS plotter, bottom finder, hard dodger, solar panels, a log/ speedometer, and an autopilot.

All I really knew about diesel engines was to keep the fuel and lube oil clean and the engine would last forever. I had been something of a motorhead in my distant youth and thought, how hard can diesel engine maintenance be? Ha! What did I know? I installed a meter to measure engine running time and paid it little heed, but I had changed the engine oil and filter every 30 to 50 hours, and also the engine fuel filter and the Racor pre-filter religiously.

After the engine died, I bled the fuel line, to little effect, and correctly guessed that I had blown the head gasket. This was bad, but there was nothing I could do about it right then, and my home in New Jersey was a long way off. I had insurance but knew that if I called a towing service, they would tow me to the nearest harbor with an engine repair shop, and I could be stuck there waiting to get the problem fixed. Now what?

On the other hand, I was in a sailboat with a pretty good inventory of headsails—a 135% genny, a 105% genny, a small working jib, and a drifter, all on hanks. The solar panels were more than enough to keep the batteries charged, and I had enough food, water, and ice for now. The old sailor’s mantra “never waste a fair wind” came to mind.

Unusual Winds

In early August, the wind on Long Island Sound usually comes up in late morning from the southwest, which would have been dead to windward, and I thought I might be able to carry sail and fetch up a little closer to Manhattan, even if I had to beat to windward to do it. Although there was a little wind out of the southeast, it was early yet, too early for usual southwesterlies. I didn’t want to think about how I would get past the notorious Hell Gate and through the East River back to New Jersey. In my experience, winds in the East River are contrary, variable, or nonexistent.

Hell Gate got its name from a set of rocks that were once at the dogleg turn in the river near Roosevelt Island across from Manhattan, and which used to snare large sailing vessels. The government eventually realized the importance of clearing the rocks, since they were creating dangers to navigation. In 1876, after tunneling through bedrock to the reef near Hell Gate, the Army Corps of Engineers blew up the reef, then in 1885 blew up the biggest and most dangerous rock, known as Flood Rock. The explosions defanged the East River, but its reputation for danger lives on.

Meanwhile, I had that light southeasterly air, which was holding nicely. This was extremely unusual. The wind never came out of the east when I needed it in the past, but it was enough to make 2 or 3 knots under sail. That was enough, with the help of the flood tide, to carry me some 25 miles to the harbor at Manhasset by late afternoon, just a few miles away from the mouth of the East River. By then, the wind had fallen so much that I had to use the outboard on my dinghy to set the hook just off the anchorage.

The next morning I was up before 6 a.m., anxiously eyeing the weather. There had been a thunderstorm the night before, and evidently that brought a stationary front. Now the wind was east-northeast, blowing 10 to 15 knots and spitting. It couldn’t have been from a better direction, if only it would hold!

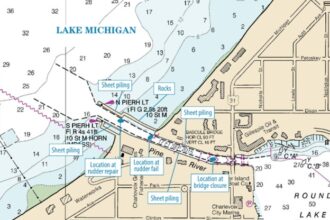

I waited for the tide to turn to start ebbing southwest through the East River, and sailed off the hook shortly after 7 a.m. Once in the East River, with my heart in my mouth and the wind over my transom, I was committed. I could imagine short-tacking down the East River; I’d seen someone doing that once, a small sailboat creeping along in the back eddies near the shore against the tide.

History and Hell Gate

However, I got lucky, and after passing Rikers Island I threaded the needle, traveling through the narrow channel between North and South Brother islands.ÁRikers Island is the sprawling, fenced-in penal colony for New York City, and just across the river and west a little is North Brother Island, the former home of Typhoid Mary, who died there in 1938. Born Mary Mallon, she was an asymptomatic typhus carrier employed as a cook in private homes, leaving disease and death in her wake. The big brick state-run sanitarium, long abandoned, lies there yet, overgrown, with trees growing through the roof. I gave it a glance as I whirled past, for here the current was running at 3 knots.

The air was filled with the constant thunder of aircraft overhead, landing and taking off from nearby LaGuardia Airport, whose runway ended in a back bay near Rikers Island. The easterlies carried me at 5 knots or so, occasionally 6 through the water even after I dropped the main, and only flying the big genoa, I got past Hell Gate a few miles further on, shortly after 10 a.m.

I’d been this way dozens of times, a few of them when it was flat calm and small boats were drifting right on top of Hell Gate where the big rock used to be, fishing for stripers. Once years before, when the ebb was running hard, I had been passed by a tug carrying a barge on the hip that had to reverse its engine to turn hard to starboard at the big swirling mass of whirlpool at the dogleg. It sent a huge wave over my deck on an otherwise pleasant, sunny day. That was a dirty trick.

Happily, I saw little commercial traffic this time. Hell Gate resembled nothing so much as a vast pot of water just on the boil, such that a boat caught in one of the circles of uprising water would spin momentarily until corrected. It was awesome but manageable. The wind stayed easterly, blowing a steady 10 to 12 knots but building. It was unnatural, this cool easterly off the ocean. In my experience, it seldom held for more than a day or so. I didn’t trust it, but what choice did I have?

As I got alongside the cross streets in Manhattan, the wind sometimes gusted but sometimes fell light. I worried that I would lose the wind and drift helplessly in the strong ebb or get headed, but it stayed easterly. There were several much bigger sailboats under power behind me, and I hoped that if I got into trouble maybe one of them could haul me as far as Governors Island off the southernmost end of Manhattan, or I could use the outboard on my dinghy to tow Pelorus along.

For the first and only time ever on the East River, I was moving so fast under sail—occasionally touching 7 knots through the water—that none of them caught up to me. At times I was moving faster than the stop-and-go vehicle traffic on the FDR Drive.

I got past Governors Island and through Buttermilk Channel in what for me was record time. Governors Island was the former official residence of Peter “Peg Leg Pete” Stuyvesant, who surrendered New Amsterdam, New York’s name at the time, to the British in 1664. Buttermilk Channel is the patch of rough, tide-chopped water alongside Governors Island, where farm boats carrying milk and produce from New Jersey would roll so much in the chop that it would, they say, churn the milk into buttermilk. Lots of history there!

Shortly after noon I was past the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge at the mouth of New York Harbor, and in my home waters on Raritan Bay. The winds stayed easterly the entire way, and by then it was blowing 20 to 25 knots. I anchored safely and gratefully inside the broad, sheltering arm of Sandy Hook, 11 miles south of the bridge. The next day, with the winds blowing northeasterly 15 to 20 knots, I happily sailed the last 10 miles to my home mooring in Keyport, on the far west side of Raritan Bay. They were the best four sailing days in a row I had all summer. My unexpected engine troubles had led me to sail past historical points, the way sailors centuries ago did, as I headed for home.

Lesson Learned

What did I do wrong? I went way past the 500 hours mark before the head gasket blew at over 800 hours running time. After consulting with a mechanic and ordering new gaskets, I was able to remove the Yanmar head at my mooring, scrape off the old head gasket, and replace the gasket and the head with little difficulty. Fortunately, the head and block hadn’t been burned by hot blowby gases. I was told that unlike automobile engines, all the small Yanmar engines had to be retorqued every 500 hours no matter what.

Retorquing the head is easy enough to do on my engine, and there are videos on YouTube to show you how. First, remove the valve cover and scrape off the oil gasket from the head and cover. Next, working diagonally, bring each lug to 65 pounds. Then adjust the valve lash to factory specs, at .008 inches cold. Finally, replace the valve cover with a new gasket, a job that usually takes me about 45 minutes or so.

What did I do right? One big thing—I didn’t waste a fair wind.

Good Old Boat Contributing Editor Cliff Moore sails Pelorus, a 26-foot AMF Paceship 26 he acquired and rebuilt after Hurricane Bob trashed it in 1991. His first boat was a Kool Cigarettes foam dinghy with no rudder or sail.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com