A sailing legend puts a wayward boat’s demise in perspective

A sailing legend puts a wayward boat’s demise in perspective

In June 2013, at about the time the remains of a century-old Lake Superior shipwreck, the freighter Henry B. Smith, were discovered 30 miles off the coast of Marquette, Michigan, a smaller but no less noble vessel joined the vast underwater graveyard, just across the Canadian border.

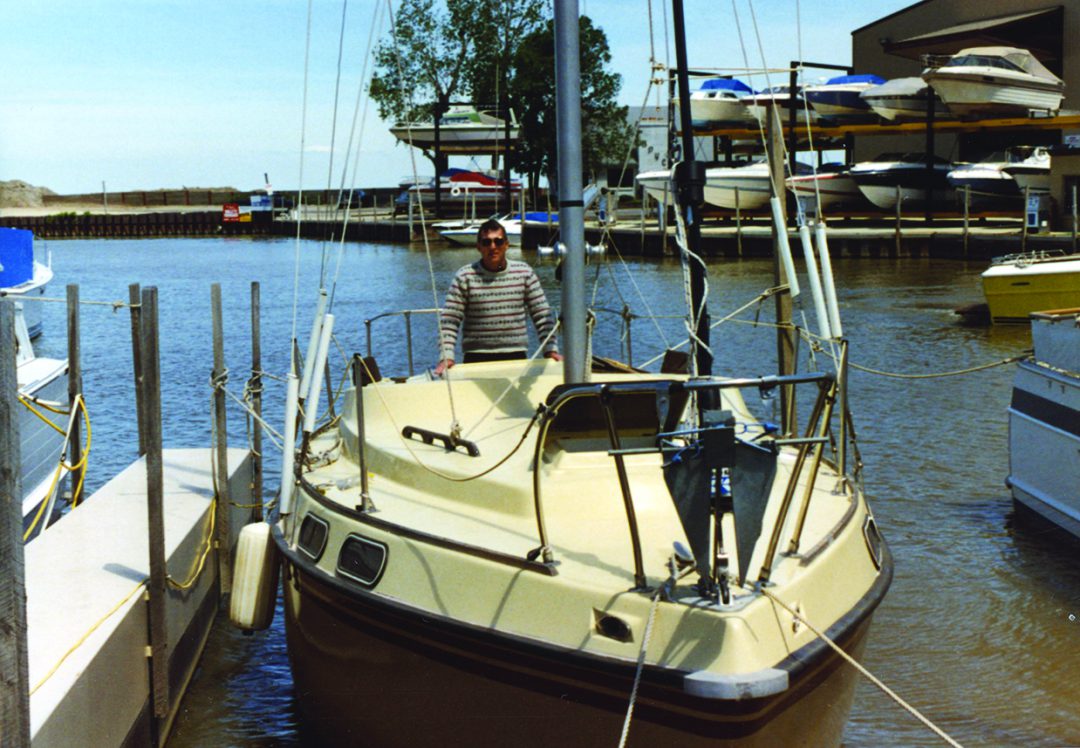

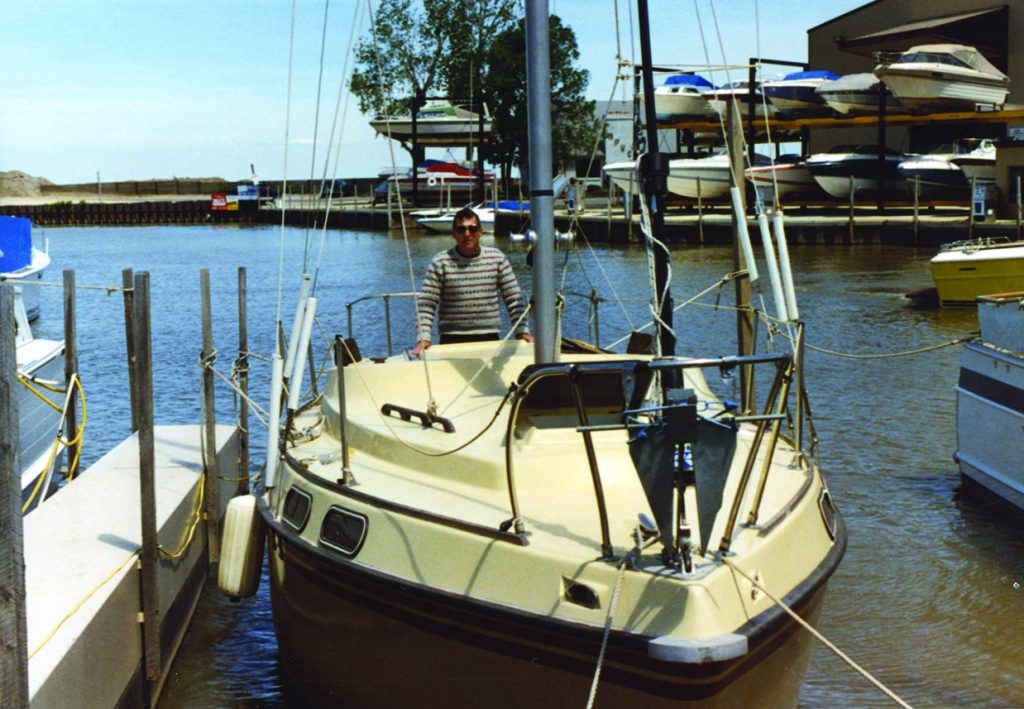

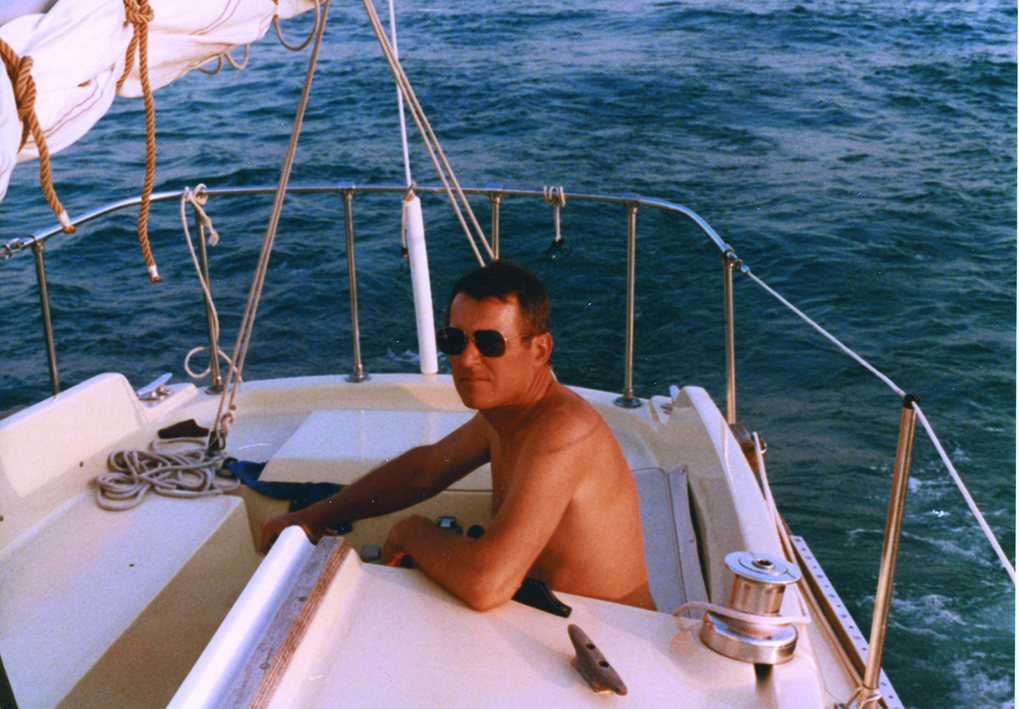

My first sailboat, the 1974 28-foot Morgan Out Island, Barracuda, was cut loose and scuttled after she reportedly broke up while being hauled from Isle Royale National Park by a Thunder Bay-based towing company. Unlike the 525-foot Smith, which sank with all 25 hands on November 10, 1913, Barracuda met her demise on a settled summer day with little fanfare and no loss of life.

We’d sold the Morgan to a longtime friend in the late 1990s when we acquired our 32-foot Down East, Chip Ahoy. Barracuda’s sinking was the crowning degradation at the end of a long line of inexplicable indignities and neglect, from an unpumped head that overflowed into the cabin to a once-distinctive tan hull besmirched by a DIY white paint job that obliterated her name.

Even after a few years had passed since Barracuda’s final passage, I was still so disgusted and angry over the witless destruction of the boat that taught me to sail that I could barely stand to look at her abuser. It was time to get over it. To let go of the ending, I needed to go back to the beginning.

We found Barracuda at Port Superior Marina. In that friendly boatyard in Bayfield, Wisconsin, I’d heard, but was never able to verify, that she had been briefly owned by Gerry Spiess, Minnesota’ singlehanded-sailing legend. He’s known for his record-setting 54-day trip from Norfolk, Virginia, to England in his 10-foot Yankee Girl, a plywood craft constructed in 1977 in his garage at White Bear Lake, Minnesota. The 3,800-mile voyage is detailed in his best- selling book, Alone Against the Atlantic.

Trading yarns

I tracked Gerry down through his friend and fellow author Marlin Bree, who chronicled Gerry’s second epic passage, across the Pacific, this time in Broken Seas. Marlin passed along my phone number to Gerry after solicitously ensuring that I was on the up-and-up.

Several weeks later, Gerry surprised me — and himself — by accidentally dialing my number instead of Marlin’s. I was so starstruck I could barely remember to ask questions.

“My energy level is down,” Gerry said, noting that his wife Sally usually does the talking for him. Because of Parkinson’s disease, he hadn’t been out sailing for a couple of years. He dismissed my offfer to call back at a better time; few sailors will pass up an opportunity for boat talk.

“She was a good boat. She was a nice size,” he told me, recalling her tan hull and topsides. “We bought her in 1988, in Lorain, near Cleveland. We sailed her back to Bayfield and eventually sold her to a doctor from Washburn (near Bayfield).” And so I learned that the steel-hulled lake freighter and fiberglass sailboat had something else common: they had both come to Lake from Lorain.

Because it was “a busy time,” Gerry and ally didn’t get to sail Barracuda often or far; the delivery passage was their longest journey. That’s about all I can tell you,” he concluded.

That’s when the interview shifted. I think I hope — Gerry got a kick out of my Barracuda stories. His kind, active listening opened a stream-of-consciousness vein that flowed like an inlet at full-moon tide. I found myself telling him about my “firsts” aboard Barracuda, including my introduction to Isle Royale National Park, negotiating Chippewa Harbor’s tricky S-shaped entry by spotlight at three in the morning, and the first time I attempted to use the galley’s alcohol stove.

“How do I light it?” I asked my husband, Scott. “You don’t,” he said.

I told him how we stared at the smelter stack in Gay, Michigan, for hours one blustery July afternoon on the south shore of the Keweenaw Peninsula. Our speed aver-aged 2 knots, as I insisted we motor against the wind in order to get back into the Portage Canal that leads to our home.

“I came from a powerboating family so I didn’t know anything about sailing,” I explained. “And I had to be to work in the morning. Do you remember the sewing-machine sound that engine made?”

“The Atomic 4 ran fine for us. It smoked the first time we ran it but no incidents after that,” Gerry said.

A rebellious boat

I told him how I’d felt sure even before it was confirmed that the Gerry Spiess had owned Barracuda due to her cocky, indomitable rebel spirit. She endured rough seas far better than I did and despite our best piloting efforts in tight situa- tions, she tended to stubbornly head toward the docks where the fanciest yachts were berthed, as if prepared to ram.

I told him how, after we sold her, she broke loose twice, once while anchored at Michigan’s Lac La Belle, where she drifted toward an impeccably restored wooden Chris-Craft runabout, but was corralled before any damage occurred. The spring before her final voyage, she dragged from her anchorage in the Sandy Bottom Cove near Dollar Bay, Michigan, where she’d been left in the ice all winter. The intrepid Barracuda managed to thread her way out a narrow, winding path of shoals, submerged piers, and rip-rap, a seemingly impossible feat, as noted by the sheriff’s department patrol officer who found her free-floating, with nary a scratch, near Julio’s Boatyard.

Barracuda’s need to go to sea was echoed by her owner, who could talk of nothing the entire winter of 2012 beyond a long-awaited return to Isle Royale in June 2013. The notion that all might be lost, including common sense, never arose. He’s worked on fishing boats in Kodiak, Alaska. He’s saved lives with his boat-tending and navigating skills. And one doesn’t travel to “the Rock,” as locals call the Isle Royale community of Rock Harbor and Isle Royale itself, without a well-tended, well-equipped vessel and crew — some rocks on the Rock are named for the locals who collided with them.

I told Gerry what little I know of how Barracuda drifted onto the unforgiving rocks in a snug cove on the south- western shore. The details are as hazy as the reasons why a sailor who had taken the dinghy to shore would simply head back home to the mainland on the Isle Royale passenger ferry when he couldn’t find his boat in the fog . . . leaving the search to others.

“He thinks the boat went out of the cove onto the lake and then drifted back in,” I said. “It sounds ridiculous. But she always did have a mind of her own.”

“Huh,” Gerry said, “That’s quite a story.”

There’s no making sense of it, but there is a certain peace in knowing that Barracuda sleeps 600 feet below, perhaps “sitting upright and largely intact” like the Smith, that other vessel that came from Lorain to meet her fate on the greatest lake of all.

“She’s resting in a good place,” said Gerry.

Aye. She is. I’m grateful to the sailing great who brought a spunky Morgan to Lake Superior and decades later helped shape her a proper eulogy.

The wave of funny, happy, uplifting memories summoned by our conversation has led to closure, compassion, and forgiveness. In time, perhaps a longtime friendship can be salvaged.