…and Two More Centerboard Cruisers

Issue 141: Nov/Dec 2021

Shoal draft is a real advantage in cruising boats; some would even say it’s a necessity, opening up a whole range of cruising options in the Bahamas, the Chesapeake Bay, Florida Keys, and elsewhere. But for racing boats, shoal draft is a disadvantage. Deeper draft allows for more efficient, high-aspect-ratio foils. It also significantly lowers the ballast center of gravity, especially with a bulb, enabling greater upwind stability and sail-carrying ability, usually at a lighter displacement.

So, the dilemma facing designers and builders is how to offer shoal draft while still maintaining good upwind performance? The boats in this design comparison illustrate solutions that three popular production builders from the 1970s and 1980s adopted, all using talented in-house design teams.

Two of our boats, the Sabre 38 and the C&C 40, offer shoal draft as an option to their standard deep-draft model. For this option, the hull mold is usually constructed so that the middle section encompassing the keel sump can be removed. Builders then install a flanged insert that contains the longer and wider sump of the shoal-draft keel, and the hull is laminated as one piece within the modified mold. Fixed draft is reduced from 6 feet 6 inches to 4 feet 3 inches for the Sabre and from 7 feet to 4 feet 9 inches for the C&C. With the centerboard down, draft increases to 8 feet and 8 feet 6 inches, respectively.

Two of our boats, the Sabre 38 and the C&C 40, offer shoal draft as an option to their standard deep-draft model. For this option, the hull mold is usually constructed so that the middle section encompassing the keel sump can be removed. Builders then install a flanged insert that contains the longer and wider sump of the shoal-draft keel, and the hull is laminated as one piece within the modified mold. Fixed draft is reduced from 6 feet 6 inches to 4 feet 3 inches for the Sabre and from 7 feet to 4 feet 9 inches for the C&C. With the centerboard down, draft increases to 8 feet and 8 feet 6 inches, respectively.

With the innovative Pearson 40, the shoal-draft configuration was the standard, not the option. Rather than adding a stub keel that houses the centerboard, Bill Shaw has taken the Ted Hood approach of employing a deeper hull form housing a large amount of internal ballast, with the board rotating into a slot in the canoe body.

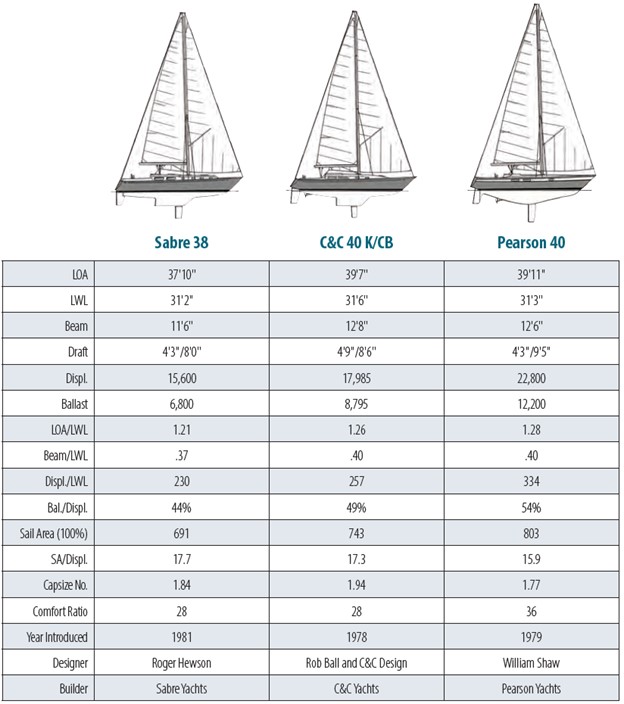

Each of these boats must then address reduced sailing stability resulting from a higher ballast center of gravity. All three of them do so by boosting ballast weight, which also increases total displacement. The Sabre increased ballast weight by 400 pounds to 6,800 pounds, while the C&C increased ballast by 885 pounds to 8,795 pounds, resulting in still respectable 44 percent and 49 percent ballast ratios. The Pearson 40, with its internal ballast mounted higher in a V-shaped hull, has taken this weight increase even further with a colossal 12,200 pounds of ballast—almost twice as much as the Sabre—achieving a ballast/displacement ratio of 54 percent!

The ballast weight increases on the Sabre and C&C still produce competitive displacement/waterline length ratios of 230 and 257, but that extra ballast in the Pearson results in 22,800 pounds displacement. This pushes the displacement/waterline length ratio to a hefty 334. That greater displacement also requires more sail area than the Sabre and C&C to achieve a sail area/displacement ratio of just 15.9, compared to the Sabre and C&C at 17.7 and 17.3.

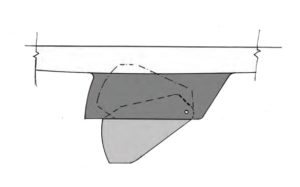

In all three boats, the centerboard acts solely as a foil and does not contribute to ballast. All three boats use high-aspect-ratio centerboards that swivel into slots in the ballast on the Sabre and the C&C, and into the canoe body of the Pearson. In this way, the centerboard and its slot are confined to areas well below the cabin sole and do not intrude into the interior. Because the Pearson has eliminated the stub keel, all the required lift to reduce leeway needs to be generated by the centerboard, so her board is proportionally larger than the Sabre and the C&C, but even with 9 feet 5 inches of draft perhaps not large enough.

The high-aspect-ratio boards on the Sabre and the C&C project from a very low-aspect-ratio keel, with both the keel and the board generating the required lift or side force to counter leeway. The board is probably far enough forward in the keel to be relatively free of the turbulence created by the high tip losses off the shallow keel, but two such different foil configurations generally don’t work well together.

A later approach adopted by C&C and Mark Ellis Design was a more triangular-shaped centerboard fabricated from fiberglass-covered cast iron that acts more as a keel extension than a separate foil. This configuration also lowers the center of gravity when the board is down and eliminates the open slot that generates increased drag. However, raising such a heavy centerboard usually requires the use of hydraulics.

All three boats sport double-spreader masthead rigs with narrow ribbon mains and large overlapping genoas common to IOR boats of that period. The Sabre and Pearson use conventional double lower shrouds, while the C&C uses in-plane lower shrouds with a mid-stay to generate more mast bend.

All three boats have capsize numbers under the threshold of 2, with the C&C the highest at 1.94 due to her greater beam. The Pearson is the lowest at 1.77 due to her heavy displacement. That factor also gives her the more favorable comfort ratio of 36, compared to 28 for the Sabre and the C&C.

Does the cruising advantage of reduced draft compensate for loss in upwind performance? Certainly not for everyone. But while it’s always a pleasure to sail a boat well upwind, at some stage of a sailing life, wider cruising horizons are more attractive than optimum upwind performance.

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Rob Mazza is a mechanical engineer and naval architect. He began his career in the 1960s as a yacht designer with C&C Yachts and Mark Ellis Design in Canada, and later Hunter Marine in the U.S. He also worked in sales and marketing of structural cores and bonding compounds with ATC Chemicals in Ontario, and Baltek in New Jersey.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com