…and Two More British-Bred Catamarans

Issue 145: July/Aug 2022

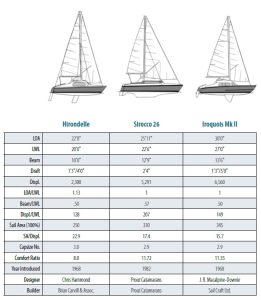

Catamarans have much to offer the cruising sailor, not least of which are increased cockpit and saloon area and relatively flat sailing. Brits seemed to have developed an affinity for production fiberglass multihulls well before North Americans, and the two boats we have chosen to compare to the Hirondelle (French for swallow) are also British-designed and built. The Hirondelle and the larger Iroquois debuted in 1968, and the Prout-designed and built Sirocco 26 entered the market 14 years later in 1982.

The 30-foot Iroquois was designed by the great J.R. “Rod” Macalpine-Downie, who rose to international recognition in 1966 as the co-designer, with Austin Farrar, of the revolutionary Lady Helmsman, three-time winner of the International C Class Catamaran Challenge Trophy. Lady Helmsman sported the first true wing mast. She currently resides at the National Maritime Museum Cornwall, home of the finest collection of historic recreational sailing craft in the world, and the Iroquois’ profile shape is quite reminiscent of this famous multihull.

The 30-foot Iroquois was designed by the great J.R. “Rod” Macalpine-Downie, who rose to international recognition in 1966 as the co-designer, with Austin Farrar, of the revolutionary Lady Helmsman, three-time winner of the International C Class Catamaran Challenge Trophy. Lady Helmsman sported the first true wing mast. She currently resides at the National Maritime Museum Cornwall, home of the finest collection of historic recreational sailing craft in the world, and the Iroquois’ profile shape is quite reminiscent of this famous multihull.

Macalpine-Downie also designed a series of boats in the 1980s named Crossbow that set several sailing speed records. This design pedigree alone, as well as her same building date as the Hirondelle, justifies the Iroquois 30’s inclusion in this comparison, despite her larger size. And, she’s a centerboarder, also significant.

The 1982 Sirocco 26 differs from the other two with her two stub keels rather than centerboards, and her rather strange “cutter” rig with the mast stepped well aft on the aft bulkhead of the cabin. Stub keels have largely displaced centerboards in modern cruising catamarans. Molded keels don’t steal room from the interior as centerboard boxes do, and they often offer increased under-sole storage. Fixed keels also eliminate complicated and expensive moving parts.

Note that the Sirocco 26’s displacement, at almost 5,300 pounds, is closer to the Iroquois’ 6,560 pounds than it is to the 23-foot Hirondelle’s 2,300 pounds. This higher displacement is also reflected in the Sirocco’s higher displacement/length waterline ratio of 207 compared to the 149 and 128 figures for the other two. This raises the obvious possibility that the Sirocco’s two stub keels actually house ballast. That higher displacement and wider beam/length waterline ratio of .57 compared to both the Hirondelle and Iroquois at .5 would greatly add to her sailing stability.

However, like all multihulls, these three boats are as stable upside down as they are right side up as exhibited by their capsize numbers of 2.9 and 3, well over the threshold of 2. I don’t expect the capsize screening formula (beam/cube root of displacement in cubic feet) was devised with multihulls in mind, but their wide beam combined with lighter displacement certainly doesn’t work in their favor. The multihulls’ lighter displacements also do not work in their favor when it comes to the Comfort Ratio, which is 8 for the Hirondelle and about 11 for the Sirocco and Iroquois.

With waterline lengths varying by 7 feet, it makes little sense to try and compare actual speed potentials between these three boats. But, remembering Uffa Fox’s famous credo that “weight belongs in steam rollers not sailboats,” we can predict that the Hirondelle, having the lightest displacement at 2,300 pounds, the lowest displacement/length waterline ratio at 128, and the highest sail area/displacement ratio of 22.9, would have the sprightliest performance.

It is my understanding that later production models of the Hirondelle had 3 feet removed from the mast, so that high sail area/displacement ratio may have been more a liability than an asset. The Sirocco 26, on the other hand, with the highest displacement/length waterline ratio of 207, even with a sail area/displacement ratio of 17.4, would be the least sprightly of the three.

Being fond of center and daggerboards myself, from my dinghy design and racing days as well as on my own boat, I think they work well on multihulls, since they provide the necessary resistance to leeway with minimum area and weight and maximum efficiency, while providing the shallowest cruising draft possible. We once chartered a 42-foot cruising catamaran with twin daggerboards in French Polynesia. While the boat had many faults, the daggerboards weren’t one of them. She sailed remarkably well.

If I were contemplating a multihull, for a piece of sailing history and heritage I’d certainly be drawn to the Iroquois. She also provides that little bit more interior volume available in a 30-footer.

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Rob Mazza is a mechanical engineer and naval architect. He began his career in the 1960s as a yacht designer with C&C Yachts and Mark Ellis Design in Canada, and later Hunter Marine in the U.S. He also worked in sales and marketing of structural cores and bonding compounds with ATC Chemicals in Ontario and Baltek in New Jersey.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com