A Classic Full-Keel Beauty

Issue 137: March/April 2021

Laurie Knight’s lifelong dream has been to own and sail her own boat, something she hopes all women will realize isn’t as hard as it looks and is well worth the effort. Her first keelboat was a Bullseye, and over time she has built her sailing knowledge and experience with friends and fellow members of the Beverly Yacht Club in Massachusetts, including crewing a few times in the Marion Bermuda Race on a Columbia 50.

In 2018, she bought Optimist, a 1968 Alberg 37 Mk I, hull #20. She saw in the boat a classic-looking, comfortable cruiser that sails well and also can compete in the occasional club race. She’s raced Optimist in the Hurricane Cup, a local club race, with an all-female crew. She also enjoys cruising with her husband and daysailing with her three adult children and the newest sailor in the family, grandson Henry, for whom she added netting on the lifelines.

Laurie isn’t alone in her love of the Alberg 37, as the boat has an equally enthusiastic owners’ group with a Facebook membership of 180. This group is how I met Laurie to review her boat, though the pandemic meant we could only meet over the phone, since I’m in Canada and she (and her boat) are in Marion, Massachusetts. For the inspection and test sail, I enjoyed a sail on another Alberg 37 in Canada owned by Jacob Weever.

History and Design

Swedish yacht designer Carl Alberg (1900-1986) designed the Alberg 37, and Whitby Boat Works in Ajax, Ontario, produced the boats. Between 1967 and 1988, about 248 Alberg 37s came off the line, with a redesign around 1971 from the Mk I to the Mk II. Principal changes included reducing the amount of wood in construction, using a fiberglass, molded floor support, and adding a molded headliner and a fiberglass toerail. The Mk II also has a molded dodger splash guard on deck. The interior was revamped to expand storage, lengthen bunks, and update the layout, including a bigger head and improved galley.

In Canada and the U.S., the Alberg 37 gained notoriety as a vessel capable of crossing oceans in comfort when compared to other offerings of that time. And, for those who love the look of classic boats, she’s a head-turner, with her long overhangs and sweeping sheer.

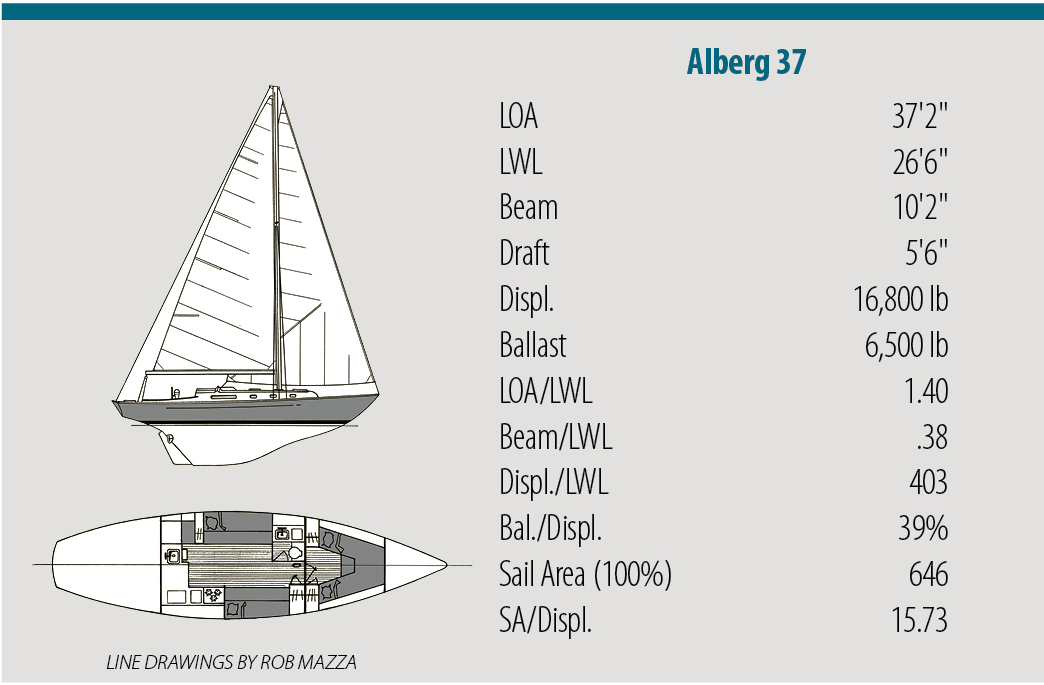

Alberg intended the design as a medium-displacement offshore racer/cruiser; the boat raced under Cruising Club of America (CCA) rule, which favored the long overhangs. Underwater, it has a full keel drawing 5 feet 6 inches, with a cutaway forefoot and a raked, keel-hung rudder, all of which reduce wetted surface area. The prop sits well protected in an aperture between the keel and the rudder, reducing the chance of snagging fishing nets or a lobster pot.

Construction

The solid fiberglass hull is typical of the era, while the deck employs a balsa core to save weight and increase stiffness.

The Mk I versions have stick-built interiors, essentially all-wood components such as plywood cabin sole, berth foundations, bulkheads, galley, etc. An advantage of this more labor-intensive method is the ability to tab bulkheads to the hull and deck to resist torsional loads. With the Mk II, the sole and other parts are molded fiberglass, which may require other methods of securing bulkheads to the deck.

Ballast is cast lead placed inside the hollow keel and glassed over so that water entering the keel from a severe grounding won’t enter the cabin. The hull-to-deck joint is an inward-facing flange on the hull that is adhesively and mechanically fastened and covered with a cap rail.

While the majority of the boats were delivered with a 23-horsepower Volvo MD2B diesel engine (or the 27-horsepower MD 11C in the Mk II), a few buyers opted for the larger 40-horsepower Westerbeke 4-107, which was offered as an option.

Rig

The 37 was sold with yawl and masthead sloop rigs. Laurie’s boat is a sloop, while my test boat has an inner forestay to set a staysail—technically a double-headsail sloop. Both sails are on furlers.

The mast is keel-stepped with a single set of spreaders, setting 646 square feet of sail, while the yawl adds 40 square feet for a total of 686. On Optimist, the 84 percent jib and a 135 percent genoa on Harken roller furlers are easily trimmed with self-tailing winches, which Laurie especially appreciates when singlehanding.

She also has a well set up reefing system for Optimist’s large mainsail, which she reports making good use of at 20 knots and above. A modest sail area-to-displacement ratio of 15.82 leaves little doubt as to Alberg’s intention to make the 37 a sensible and safe design for offshore work.

On Deck

The foredeck is wide and clear to accommodate a windlass, which many owners have installed to handle ground tackle and complement the integrated anchor rollers and large chain locker.

The cockpit is much like the rest of the boat—long and narrow. There is a bridge deck that protects the small (seaworthy) companionway, plus a reasonably high coaming. The helm sits well forward in the cockpit, and while aesthetically it looks a bit off, Laurie says that it makes singlehanding easier and helps her stay protected behind the dodger in rough weather.

At the aft end of the cockpit is an elevated afterdeck (with a lazarette below) that provides storage and helps prevent the cockpit from shipping a wave in a following sea. Both cockpit seats open to deep and voluminous lockers to store gear and house systems.

Laurie does a great deal of shorthanded sailing, and while she’s led all sheets aft to the cockpit, she has decided for now to leave the halyards at the mast.

Below Deck

The Mk I and the Mk II interior layouts are significantly different; the builders even made changes within the same model year-to-year. While the Mk I has straight opposing settees with pilot berths above, the Mk II has an L-shaped settee to port and storage above the settees instead of berths. With a beam of just over 10 feet, the cabin feels narrow compared to more modern designs.

Stepping down Optimist’s companionway, the L-shaped galley is to starboard with an aft-facing nav table and seat to port. On some boats, this nav area has a quarter berth aft with a front-facing navigation table. Both of these arrangements are tucked behind a partial bulkhead, which segregates this area from the saloon and houses a well-positioned wet locker.

The galley sink is nearly on the centerline of the boat, which makes it ergonomically excellent underway on either tack. Optimist has refrigeration in her deep icebox and pressure water.

Laurie added water tank gauges (an improvement over a dipstick). She rerouted plumbing to change the head from seawater to freshwater to eliminate odors and has a greywater sump for the shower, all of which make for a clean-smelling boat.

The feeling of a classic yacht design does not stop outside; beautiful teak flooring, wood furniture, hull liner, bulkheads, and joinery show the craftsmanship put into these boats. Though the wood can make the cabin seem dark, abundant opening portlights and large overhead hatches offset the issue. The cabin feels very cozy, and when underway it is never a stretch for a solid handhold, nor is it hard to brace oneself.

The midship position of the settees and pilot berths minimizes motion in a seaway, and leecloths add safety and security.

The port side of the saloon features a bulkhead-mounted table to convert the sitting area into a dining area. Pull-down doors under all bunks/settees allow access to voluminous storage.

Forward of the main cabin is a large hanging locker to starboard, with a fully enclosed head to port featuring a marine head, sink, and integrated shower. Laurie was quick to point out a feature of the Alberg 37 that might be underappreciated by a male skipper: the toilet faces aft and is just off the boat’s centerline, making it easy to use on either tack.

A notable drawback of the V-berth is the length of slightly under 6 feet; this measurement varies also with the model year. Some owners reportedly have modified the forward chain locker to extend the berth.

Underway

With a displacement of 16,800 pounds, the Alberg 37 has enough mass to handle swell and chop without bouncing around. “Optimist feels like she rides in the ocean, not on the ocean,” Laurie says. “Even in heavy swells, Optimist feels like she is cutting forward and feels solid and confident.”

On the wind, the Alberg 37 points nicely with a solid motion. The boat likes to be sailed with some heel and seems a bit tender at first, but once heeled it digs in a shoulder and stabilizes with a good turn of speed.

From the helm there are reasonable sightlines even with a dodger. The mainsheet resides at the back of the cockpit behind the helmsman, while the jib sheets are forward, providing good separation of control lines if sailing with crew who do not care to bang elbows while tacking. Those who enjoy beer-can racing should note the boat has an average PHRF rating of 162.

Conclusion

Even a well-built boat like the Alberg 37 will have some issues related to longevity. One of the first things that Laurie did was replace some of the through-hull hoses, which were likely as old as the boat and in terrible shape; she also engaged a local yard to replace a through-hull.

Most of these boats will require electrical upgrades and careful attention to hoses, through-hulls, and the engine. The balsa-cored decks should be sounded for possible delamination or rot, and although the bronze ports are striking and add to the boat’s appearance, they are also a weak point and should be replaced with fully bolted ports or storm covers for offshore work.

An internet search quickly revealed two things about the Alberg 37: First, there is a very active owners’ group, which is a great resource; second, there are not many Alberg 37s for sale (I found only two, for $28,000 and $35,000). Both facts lead one to conclude that this is a well-loved, well-thought-out design that owners hang on to.

There is little doubt that the aesthetics of the Alberg 37 add to its popularity, but its sweetness under sail reveals its perfect blend of form and function. For those who love classic lines, can endure the maintenance and upgrades inherent in an older boat, and are looking for a capable cruising and club-racing boat, the Alberg 37 may fit the bill.

Robb Lovell is an avid Great Lakes sailor and outdoorsman from Amherstburg, Ontario, who enjoys cruising and racing. He cruises a Hallman 20 named Stout and enjoys racing Force 5 dinghies, as well as racing onboard keelboats at Lasalle Mariners Yacht Club. When not sailing, Robb enjoys mountain biking, snowboarding, kayaking, and competing in Ironman races.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com