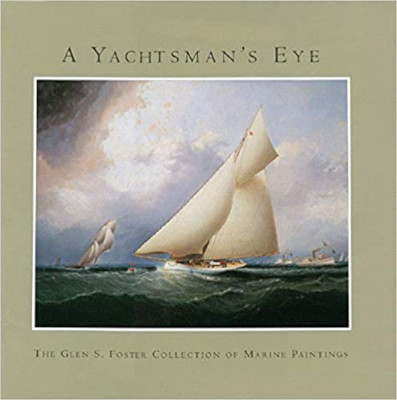

Wrestling sheets while wrestling the cancer that killed him, he’d won the international 5.5-Meter dinghy championship. He’d been a beloved force in the legendary New York Yacht Club, and a booster, adviser, and crew for America’s Cup challengers. He’d introduced America to the Finn, that most temperamental of all Olympic dinghies. He’d crewed with the famous from Conner to Coutts, competed from Stockholm to Sydney — often earning winner’s laurels — yet was never too busy or ill to consult, teach, and support in the sport he loved. Plus, Glenn S. Foster, world-class sailor, stockbroker and art connoisseur had collected a king’s ransom of marine art. He’d acquired the means, the education, and an eye as competitive in art as it was in sailing. Celebrating Foster’s unerring artistic tastes, this astonishing array of great old boats was edited by his close friend, knowledgeable art critic Alan Granby.

The term “marine art” covers a broad sea, from the angular watercolors of Marin to the dappled waterscapes of Monet, past the Dutch masters, beyond the Bayeux Tapestry, way back to the stylized fleet of a female Pharaoh four thousand years ago. But to Foster, “marine art” instead meant the past two centuries of outstanding American and British wooden boats painted in characteristic action, paintings that evoke the scent of breeze, sway of deck, creak of spar, arch of spray, and vastness of clouds — all the pleasurable details of the actual sailing experience.

Not for Foster impressionism, expressionism, abstractions, or theatrical shipwrecks, not Turner’s burnished mists or Homer’s stoic crews, nor kitsch clipper ships under clouds of sail or classic Dutch seascapes. A few pictures do show men-o’-war wreathed in fiery broadsides. But Foster preferred sunlit, well-trimmed, identifiable, accurately rigged yachts and ships in Bristol condition, often heeled under dramatic skies. Based on seamanlike knowledge, the realist artists understood rigs, knew when to reef, why to luff, what to trim, where to roost. Knowing the details of sailing helped them excel in paintings about sailing.

So, what’s not to like about this book? Nothing, unless a problem hides within the collection itself. Great art can be great marine art, but this collection is great marine art, by and large (sailor’s talk!) — but not great art, not the likes of, say, Van Gogh. Clarity of image trumps visual challenges, for Foster often preferred representational painters of memorable yachts — e.g., William Bradford, James. E. Butterworth, Robert Salmon, and Fitz Hugh Lane. This makes for a happy and gorgeous coffee-table book. While shore-bound, sailors viewing it will find hope in their dreams and pleasure in Foster’s reality. That’s why you need it.

A Yachtsman’s Eye: The Glen S. Foster Collection of Marine Paintings edited by Alan Granby (Independence Seaport Museum and W. B. Norton Co., 2005; 248 pages)