ILLUSTRATIONS BY ROB MAZZA

…and Two More Performance Cruisers.

Issue 138: May/June 2021

I assumed the Passport 42 would be a Bob Perry design, an assumption further reinforced when I saw she had a Valiant 40-style canoe stern. However, despite the fact that Bob designed seven boats for Passport, the 42 is a Stan Huntingford design, as is the 1982 Passport 51, also with a canoe stern. I wish I knew more about Huntington, a fellow Canadian, but our paths never crossed, and there is a distinct lack of information online.

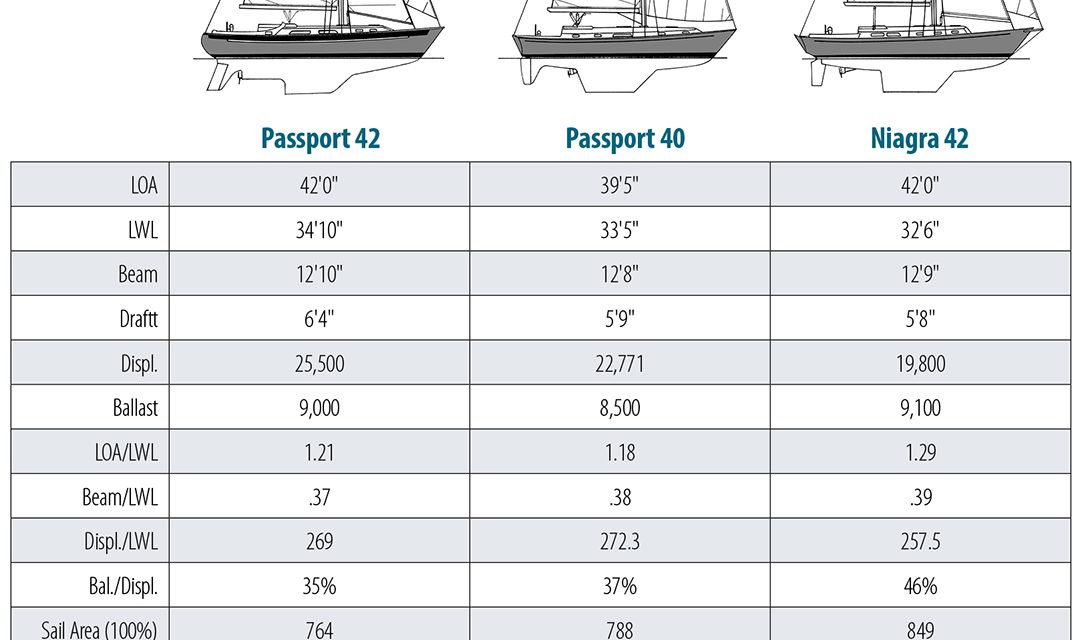

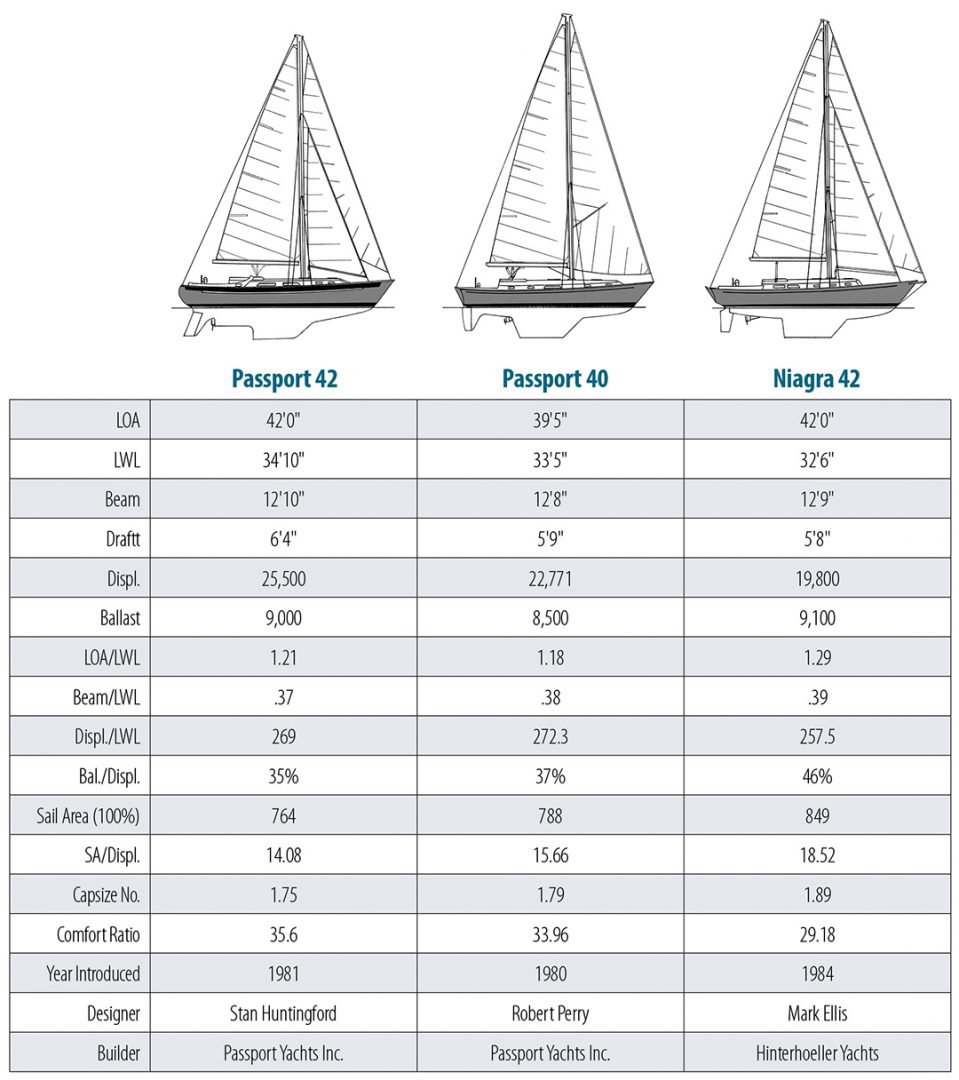

The 1973 Perry-designed Valiant 40 would seem to be the logical boat to compare to the Passport 42, but that would be too obvious and would be comparing boats from different decades, despite their similarities. I thought it best, instead, to compare her to a later Perry design, coincidentally by the same builder as the 42, the 1980 Passport 40. This would allow the inclusion of a Perry design contemporary with the Huntingford design and perhaps one more representative of Perry’s evolved thinking on the breed. The third boat in our comparison is the Mark Ellis-designed, George Hinterhoeller-built, Niagara 42. The 42 was in the tooling stage when I joined Mark in 1985, so I was not directly involved in her design, although I did become involved with interior liner discussions and details.

The term “performance cruiser” is a good way to describe these three boats because they all incorporate split keel and rudder, as well as other design features introduced on race boats. With regard to rudders, note that the Passport 40 and 42 incorporate a small, leading-edge skeg, while the Niagara employs an all-movable rudder. The rather exaggerated angle of rudder rake on the Passport 42 contrasts with the more vertical rudder shafts of the Passport 40 and the Niagara 42. This rake seems more in character with boats from the ’70s than the ’80s.

The performance aspect of cruising is also illustrated in their rigs, each using tall, double-spreader, cutter rigs with large foretriangles and relatively narrow mainsails. I have shown the Passport 40 with an open foretriangle, but a quick Google search shows a large number with staysail stays. The challenge in any cutter rig is determining how best to adequately support the mast in way of the staysail stay hounds. Running backstays are the most efficient method, but a nuisance, so it is interesting to see the Passport 42 and the Niagara use fixed staysail shrouds set aft of the lower shroud chainplates. This restricts the amount the main can be eased off the wind but greatly simplifies tacking and jibing.

The size of these three boats is reflected in both their waterline lengths and their displacements. The Passport 42 is the largest at 34 feet 10 inches waterline length and 25,500 pounds displacement. The Passport 40 is next at 33 feet 5 inches and 22,771 pounds, and the Niagara 42 the smallest at 32 feet 6 inches and 19,800 pounds. The performance aspect is also evident in their displacement/waterline length ratios, with a low of 258 for the lighter Niagara, and 269 and 272 for the Passport 42 and 40, respectively. Traditional heavy-displacement, full-keel cruising designs are generally well over 300.

Sail areas are a consistent 764 and 788 for the Passport 42 and 40, and a much higher 849 for the lighter Niagara 42. The Niagara is the only one of the three that uses a bowsprit. This increases the J dimension substantially over the other two boats, helping to generate that larger sail area. Those numbers produce a range of sail area/displacement ratios from a low of 14.08 for the Passport 42, a moderate 15.66 for the 40, and a performance-oriented 18.52 for the Niagara 42.

Ballast weights are consistent, ranging from a low of 8,500 pounds for the Passport 40 to a high of 9,100 pounds for the lighter Niagara 42. This reflects itself in the ballast/displacement ratios of 35 percent for the Passport 42 and a high of 46 percent for the Niagara 42. (That high ballast ratio, low displacement/waterline length, and high sail area/displacement ratio causes me to suspect that the Niagara’s published displacement may be on the light side.)

Beams are also consistent, varying only 2 inches for all three boats, producing narrow beam/waterline length ratios of .37 to .39. These relatively narrow beams on moderate displacements yield very safe capsize numbers of 1.75, 1.79, and 1.89, all comfortably below the threshold of 2 and all in inverse proportion to the displacement figures. Comfort ratios for the three boats decline in direct relation to displacement, with the heavier Passport 42 coming in at 35.6, the lighter Passport 40 yielding 33.96, and the lightest Niagara 42 coming in at a slightly less comfortable, but still respectable, 29.18.

All three exhibit classic shear lines, traditional transom configurations, narrow beams, moderate overhangs combined with straight stems, and relatively tall rigs, indicating a satisfying combination of traditional CCA aesthetics with the less egregious aspects of IOR performance. In that regard, it’s hard to pick a winner among these three, but if I had to, I’d lean towards the Niagara, while acknowledging my obvious bias.

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Rob Mazza set out on his career as a naval architect in the late 1960s, when he began working for Cuthbertson & Cassian. He’s been familiar with good old boats from the time they were new and had a hand in designing a good many of them.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com