Boundless shows off the handsome profile and solid seakindliness the Passport 42 is known for. Photo courtesy of Julian Jones, sailboundless.com

Checking All the Boxes

Issue 138: May/June 2021

After only a few dates, Scott Voltz and Connie Bunyer knew two things: They liked each other, and they liked sailing. Well…Scott knew he loved sailing; Connie was pretty sure she would, even though she’d never been. Scott worked as a computer guy for Seattle’s Harborview Hospital and was a part-time sailing instructor for the University of Washington’s sailing club. Connie was a musician and single mom soon to have an empty nest. Scott invited Connie to join him and some friends on a sailing charter in Mexico.

“The boat was an old Morgan called Seascape,” Scott says. “We called it Seascrape because the bottom was covered with mussels and barnacles that would scrape you bloody when you were swimming and brushed against it.” The boat left much to be desired, but they loved the experience.

They decided to look for a boat that would be comfortable to live aboard and could cruise Mexico and beyond. Scott had owned a Newport 27 for many years, and his work as a sailing instructor had informed his opinions about boats. Connie trusted she would know The Boat when it presented itself to her.

“We looked at about 30 boats, but none of them were just right,” Scott says. Then they spotted a 1981 Passport 42 for sale in San Diego. For Scott, the Passport 42 checked all the boxes. She was a heavy-displacement cutter, and inside she had a spacious galley, staterooms fore and aft, and plenty of headroom for his 6-foot 2-inch frame. With a canoe stern and a pleasing sheer, she was the very profile of a no-nonsense, serious cruising boat.

The boat’s original owner loved her but had aged out of boat ownership. The couple’s plans for the boat thrilled him, and everyone happily made a deal. Scott and Connie quit their jobs, sold everything that wouldn’t fit on their new boat—named Traveler—and began their adventure. They sailed from San Diego to Ensenada, Mexico, to begin a five-month refit. The following October, they began a four-year cruise of the Sea of Cortez and Mexico’s Gold Coast.

While in La Paz, they decided to sail to Hawaii on their return to the Pacific Northwest. They made a 21-day, 2,700-mile crossing from Cabo San Lucas to Hilo, Hawaii. After a bit of island hopping in Hawaii, they sailed 21 days north and east to landfall in Ketchikan, Alaska. They made their way down the coast of British Columbia to Washington, where they lived aboard in Olympia for a year, then acquired a small home and moved off Traveler.

Eventually, they bought a small day-charter business, named it Mystic Journeys on Traveler, and worked for the next two years booking up to 80 charters annually. Most were “three-hour tours” sailing on Olympia’s Budd Inlet, but if a client wanted something different, they tried to make it happen. For instance, one couple only wanted to dine and sleep aboard. Scott and Connie set them up in the afternoon and left them to enjoy Traveler until the next morning.

For most of their clients, it’s the first time ever on a sailboat, and both of them find it deeply rewarding to introduce new people to sailing. In 2020, the pandemic prevented them from working their business, but they plan to resume as soon as possible.

History and Design

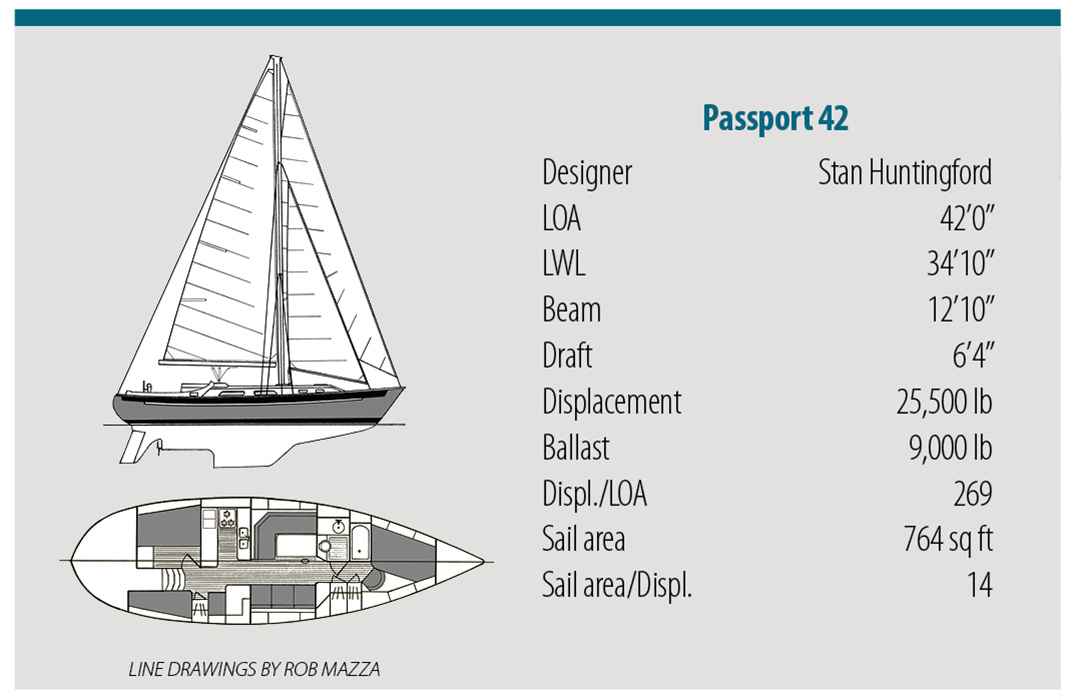

Designed by Canadian Stan Huntingford, the Passport 42 first came off the line at Solar Marine in Taiwan in 1980 and sometimes was referred to as the Solar 42. In 1983, Miracle Marine took over construction, and by 1987 production moved to Hai Yang Boat Building. A variety of importers marketed them in North America, and about 50 boats were produced under the Passport 42 name between 1981 and 1988.

Huntingford’s other designs were largely built in Taiwan and Canada during the late 1970s and early ’80s, including the Slocum 43, which differs only slightly from the Passport 42, and a 51-footer for Passport in 1982. He also designed the Cooper 353, 367, 416, and 508; the Maple Leaf 42, 45, 48, and 54; and several other cruising boats in the 35- to 50-foot range.

With its sharp bow and canoe stern, the Passport 42 resembles Robert Perry’s Valiant series, though on closer inspection, the Passport carries the 12-foot-10-inch-wide beam further aft, providing a roomier interior. The stern is not the refined Nordic-style shape of many Perry designs, but rather a fuller, more hemispheric profile. Scott says it does a fine job of keeping water out of the cockpit in a following sea.

Underwater, the Passport 42 has a lot going on—a deep forefoot that blends into a fin keel with a long chord, and an elongated, molded strut with bearing to support the prop shaft. Further aft is a beefy skeg protecting the rudder. The maximum draft is 6 feet 4 inches. This tried-and-true configuration is reassuring to many bluewater sailors, but it also racks up a lot of wetted surface that, combined with relatively small sail area, can make the boat sluggish in light winds and through a tack.

The design weight of the Passport 42 is 25,500 pounds with ballast accounting for 9,000 of that. With ample stowage below and cruising sailors as its primary market, it’s a safe bet that most boats are a good deal heavier—probably closer to 30,000 pounds. Scott says the weight of the boat gives him confidence and provides an easy motion at sea.

Construction

One of the things Scott and Connie like most about their Passport is the robust construction. The fiberglass hull seems to be thick in the right places. Like most Taiwanese boats, the interior teak joinery is impressive. Scott was even more impressed when he was able to remove and replace two 55-gallon black iron (carbon steel) diesel tanks from under the cockpit sole. They just fit through a locker door in the aft cabin without removing any joinery.

Scott and Connie’s Passport came with teak decks and cabintop—a ubiquitous feature of Taiwanese boats of this period. Forty years of hot Southern California sun, plus time in Mexico and Hawaii, have had their way with them. This is a common refrain in these teak-decked boats; the caulking used to seal the teak bungs over deck screws deteriorates and allows water to migrate down the screw, past the layer of fiberglass underneath, and into the deck core, potentially causing rot and a spongy feel underfoot. For many, the cost and skill to repair is prohibitive. The good news is that if the core is still solid, the fiberglass deck can be made perfectly serviceable. Scott and Connie are removing the boards a section at a time, filling and fairing the screw holes, and painting with white non-skid paint. The teak boards on the cabintop are in the best shape, and Scott and Connie are considering leaving them for now.

The ballast in the keel is fully encapsulated with fiberglass, which obviates the need for keel bolts. Construction and layup varied with the sundry builders; one owner says the hulls are solid fiberglass below the waterline and cored with foam above, and that the deck is cored with 4-inch teak squares to limit water migration.

The interior is stick-built with bulkheads tabbed to the hull. The shower/tub assembly is a fiberglass module, as are the interior walls of the head. During a haulout in Mazatlán, Scott and Connie hired a yard to strip the hull for blisters and reseal it with vinylester resin.

Chainplates on the Passport 42 were glassed in, a practice that most boatbuilders discontinued in the 1960s. Glassing over stainless steel is a bad idea because of crevice corrosion, the inability to inspect, and the difficulty replacing parts. Many Passport owners have dug out the old chainplates and replaced them, but it’s a big job. Scott and Connie got a quote for $10,000 and are saving their pennies to get this done.

The saloon of Boundless highlights the beautiful interior joinery typical of these boats. Photo courtesy of Julian Jones, sailboundless.com

Below Deck

The companionway is off center to starboard to allow more space for the portside aft cabin. “From Mexico to Hawaii and Hawaii to Alaska we were always on the starboard tack,” Scott says. “So it was nice to climb down into the cabin on the high side. The combination of a low dodger and bridge deck made it tough for me to get through the hatch, but once I did, it was easy to descend the stairs facing forward.”

At the bottom of the stairs to port is an aft cabin with a large double bunk and reasonable storage. A small hatch and two portlights keep it from feeling like a teak-clad cave. To starboard is a quarter berth with a navigation station featuring a large chart table. The arrangement allows quick access from the cockpit to the navigation station and a comfortable, secure berth for the off watch.

Although these galley configurations are slightly different, each provides a secure space for the offshore chef. Boundless photo courtesy of Julian Jones, sailboundless.com

Forward of the aft cabin is the galley. Its U shape and size make it easy for the cook to feel secure in a seaway. It is just large enough that a second person can wash dishes or chop vegetables, what my wife calls a “two-butt galley.” The double sink is on the centerline of the boat. The refrigerator and freezer are huge, with access from the top and the side.

Forward of the galley is a roomy dinette, which faces a settee long enough to serve as a single bunk. The keel-stepped mast is at the end of the forward seat of the dinette and close to the bulkhead for the head.

Gemini photo courtesy of Two the Horizon Sailing, @twothehorizon.

The head is on the port side and is spacious enough to have a small tub, though Scott and Connie say they have only used it as a shower. In some Passports, this feature is replaced with a dedicated shower stall.

Starboard of the head is a hanging locker and stowage. Forward of that is a cabin with a double bunk on the port side and a comfy seat built in to starboard. Overall, the layout is traditional, practical, and spacious for a 42-footer.

Mechanicals

The steering on the Passport 42 is a wheel with chain-to-cable and a heavy bronze quadrant, providing peace of mind for sailors enduring prolonged difficult conditions.

The boats came with a Perkins 4-108 diesel mounted below the cabin sole near the sinks. This location keeps the weight low, although it increases the risk of water from the engine exhaust getting sucked into the engine cylinders—the dreaded waterlock. And, for full access to the engine, you need to dismantle part of the cabinetry. Scott says he has spent a lot of time on his belly working on the engine. Considering the age of the boats, those with an original engine will most likely need a transplant; Traveler’s was tired, cranky, and leaked oil, so they repowered with a Beta.

Traveler has tanks for 150 gallons of freshwater and 110 gallons of diesel. This may differ in other Passport 42s. Traveler and other sisterships have had problems with leaky tanks. There have been cracks reported in the fiberglass blackwater tank, and in addition to replacing the black iron fuel tanks on Traveler, Scott and Connie also had to deal with the stainless steel freshwater tanks under the cabin sole developing pinhole leaks. They fixed them by cleaning and applying a spray sealant to the interior of the tank. Good inspection and cleaning ports in those tanks made that fix possible.

The cockpit layout is designed with offshore security in mind. Photo courtesy of Julian Jones, sailboundless.com

On Deck

The cockpit is small and secure. Behind the wheel, the helmsman stands on a raised portion of the sole to allow better viewing over the cabintop. While a good idea in terms of enhancing visibility, during our sea trial I stumbled on it every time I moved from the main part of the cockpit to behind the wheel. That was mostly because I’m clumsy, and it’s the kind of thing that wouldn’t be a problem after I got used to the boat. The cockpit seats, while long enough to recline, are not long enough to lay down and sleep.

The sidedecks are wide and the shrouds terminate near the toerail, so going forward is easy, generally unobstructed, and secure with good handholds. The cabintop is also a nice height for sitting, something Scott and Connie use to good effect during their day charters. They festoon the cabintop forward of the mast with cushions and stadium chairs, and that’s where the guests usually hang out for the duration of the voyage. Traveler’s stability and the high double lifelines make everyone feel comfortable.

The teak decks and cabintop, typical of most Passport 42s that were built in Taiwan, often need repair after 40-plus years. Photo courtesty of Two the Horizon Sailing, @twothehorizon.

Underway and Conclusion

The Passport 42 has a cutter rig, a favorite of cruisers with bluewater ambitions. The mainsail and foretriangle have a combined square footage of about 765 square feet, which feels conservative for a boat this heavy. The right staysail and jib or genoa combination could jazz things up considerably. Scott and Connie have an asymmetrical spinnaker that helps a lot in light winds.

We went sailing in a light breeze, typical of sunny days on Puget Sound. Traveler ghosted along nicely under main and a roller-furling genoa. She was slow to accelerate and had to be coaxed through some of her tacks, but otherwise performed well. Scott says she really sings when the wind picks up and doesn’t have any bad habits.

Traveler’s guests enjoy the view from the foredeck while touring the waters of Olympia, Washington.

Despite the predictable issues that are typical with boats of this era, the Passport 42 remains a coveted catch among those who want to know that they can take safely to blue water or even just cruise coastally in comfort. Depending on the boat’s age, upgrades, and background, they can range quite widely in price. A brief check of the used boat market found a 1981 model for sale at $72,000, and a 1988 for $146,500.

The designer of the Passport 42 was a conscientious craftsman who set out to answer the needs of bluewater cruisers. Traveler is a case in point: She is seaworthy and has an extensive list of features that serious offshore sailors value. She checks nearly every box—some of them twice.

Brandon Ford, a former reporter, editor, and public information officer, and his wife, Virginia, recently returned from a two-year cruise to California, Mexico, and seven of the eight main Hawaiian Islands. Before their cruise they spent three years refitting their 1971 Columbia 43, Oceanus. Lifelong sailors, they continue to live aboard Oceanus and cruise the Salish Sea from their home base in Olympia, Washington.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com