A series of misjudgments leads to a nearly catastrophic bridge encounter.

Issue 140: Sept/Oct 2021

My wife, Terri, and I, aboard our 2006 Beneteau 423, departed our home port of Clear Lake, Texas, to start the adventure of our lifetime, navigating The Great Loop. Now, three years into our voyage, and after a year-long detour up the St. Lawrence River and gunkholing down coastal Nova Scotia and Maine, we were continuing south again, to pick up the Hudson River route inland, the path to the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes.

After a brief stay in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and neighboring Kittery, Maine, we were heading just 15 nautical miles down the coast to Newburyport, Massachusetts, a quaint town just inside the mouth of the Merrimack River.

Planning this short passage, we consulted the coastal pilot charts and learned it was best to enter the Merrimack River Inlet on a rising tide, and definitely not when the ebb is flowing against an easterly gale. Having never been into Newburyport, we decided to take the prudent course, and thus planned our departure from Kittery by working backwards from our optimal destination arrival time. After looking at the weather and calculating our forecast time en route, we planned to leave Kittery at 0900 hours the next day.

We were up at 0800 hours. We’d spent the night on the Piscataqua River, end-tied to a single-dock, 25-boat marina. Looming over us, about only two boat lengths in front of our bow, was Memorial Bridge, a lift bridge just upriver of our location. We were aimed as though poised to drive right under the bridge, though even if we had intended to do so—we were, instead, headed downriver, toward the Atlantic Ocean—this wasn’t possible, as our 57-foot mast was about 20 feet taller than the clearance the bridge afforded in its current configuration.

But this part of the Piscataqua River is still tidal, and the flood tide was creating a current of about 2 knots, pushing our boat from astern, towards the bridge. Were our docklines to suddenly part, I imagined the current would drive our Beneteau right into the bridge, bow first.

Docklines secured us bow and stern on the starboard side. Terri and I discussed how best to extricate our boat from the dock safely, given the particular, difficult circumstances. We boiled it down to four options:

1. We could wait for the tide to turn. This was Terri’s preference, but would delay our departure by at least two hours.

2. We could turn our boat around at the dock, so that the bow pointed downriver, away from the bridge and into the current. This would mean we could depart the dock in forward gear and not have to back up and turn around. The best, easiest, and safest way of doing this was to simply leave the bow line secured, let loose the stern line, and allow the boat to be swept around by the current. We could do this because our dock lines were plenty long and there was no other boat in front of us on the dock; we had plenty of room. I argued against this approach out of concern that we might scuff the gelcoat during this operation—and I really did not think it was necessary.

3. We could wait for the dockmaster or another boater to appear on the scene and help us get off the dock.

4. We could put the boat in reverse, release the dock lines simultaneously, and apply power to back far enough away from the bridge until it was safe to shift into forward and complete a U-turn.

We went around in circles debating these options. I got impatient and finally decided we would safely and easily execute the fourth option, overriding Terri’s concerns. (I’ve found that, generally, this is not a good idea. I was about to learn it again.)

All of our bow, stern, and spring lines are three-strand, 5/8-inch diameter, and 50 feet long. We removed the spring lines and doubled the bow and stern lines back to the boat, leaving them just looped around the dock cleats, so we could let go from the boat, Terri at the bow, me at the stern.

The plan, which we discussed carefully before departing, was for each of us to let go the bow and stern lines at the same time by slacking off each line and throwing the loop off the dock cleat. Then, we’d allow the current to ease the boat away from the dock while I backed us up using our 55-horsepower Volvo-Penta diesel, which has always been reliable and responsive. Before we untied anything, I warmed up the engine and powered astern, just to make sure the engine and prop could counter the current; they did so easily.

At 0900, we were ready to go. I put the engine into reverse gear at near idle speed to reduce the tension on the stern line and gave the command to cast off. Terri quickly and easily cast off the bow line as planned. I did not.

Rather than leave the cockpit to release the stern line from the side deck, I tried to do so through an open side panel of our cockpit enclosure. But the enclosure made this difficult, and I realized the current was pushing the stern away from the dock faster than I could create enough slack to toss off the line looped around the dock cleat.

After two or three frantic failed attempts, I just let the running end of the line go (the standing end of the line was attached to the boat’s stern cleat). Just as the bitter end of the line slipped through my fingers, I realized in horror that I’d made a terrible error in judgment. The line ran freely around the dock cleat, and suddenly, 45 feet of dockline was in the water, trailing from the stern cleat.

This meant that I would not be able to power astern, for fear of wrapping the line round the prop. I needed two hands to wrestle the stern line aboard, but I was also trying to hold onto the wheel and tend the throttle. The stern continued to swing out, gaining momentum, the boat turning parallel to the bridge.

I glanced forward and saw Terri calmly coiling up the bow line to stow it, unaware of my situation. I yelled for her to drop the line and rush back to help me. She instantly realized what was happening and hurried aft, hauling the stern line aboard in record time.

I immediately went full power in reverse. I had the helm hard over to starboard, but we had no steerage and were barely making sternway. By now, we were essentially broadside to the bridge, sweeping rapidly down on it, and I was out of options. I throttled back and put the engine into neutral. Going ahead would have spun the stern into the bridge even faster, and we could not go back fast enough to do any good.

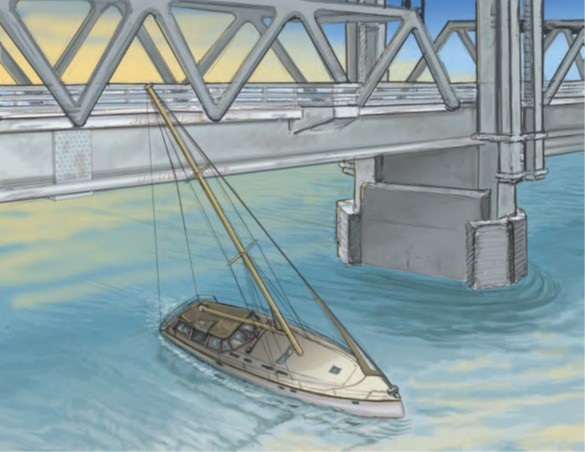

Then, we were swept broadside down onto the fixed part of the bridge, a hundred feet or so north of the lifting section. We struck it between all vertical supports and abutments. Our boat has twin backstays, and the port backstay ground against the lower girder, about 20 feet below the masthead.

As the backstay met a fixed object, the mast vibrated, the boat shuddered, and we heeled over to starboard. I was surprised—and maybe the relative springiness of the stay served to dampen forces—at how gently we went over. It was not like getting slammed unexpectedly by a 50-knot gust on the beam, but more like filling the main in a 10-knot breeze.

Nevertheless, the motion clearly felt inexorable and unstoppable; we were going to be swept under the bridge and lose our boat, our home, maybe our lives. And in this time, I also thought that if we and our boat survived being swept under the bridge and emerged damaged but still afloat on the other side, then we were headed for a marina full of boats that we would surely be swept into, the consequences of my errors spreading beyond ourselves.

All these thoughts flashed through my brain while time stood still, and I froze. Within a few seconds, we heeled to at least 20 degrees or so. Neither of us had said a word or made an exclamation. I had a firm grip on the wheel and binnacle and was about to yell to Terri to hold on tight, after I saw her on the starboard sidedeck that was rolling into the water.

And then, we got lucky. Even though we hit stern-first, the force of the current on the rudder continued to swing the bow around as we heeled, pivoting slowly about the backstay where it contacted the bridge girder. As we were being swept over and under, the bow slowly started to point back downriver, away from the bridge. As we pivoted, the force of the current on the rudder and keel reduced slightly and the heel also eased.

We hung there in a sort of equilibrium for a couple of seconds when I was jolted into action by a burst of enthusi¬astic verbal encouragement from Terri (something along the lines of “Gun it!”). I gunned the engine in forward, the helm was already hard to starboard, and we powered ahead to starboard and turned out from under the bridge. The backstay scraped along the girder as we shot forward, but I heard nothing over the roar of the engine. We were suddenly upright and moving away from the bridge.

Although it seemed much longer at the time, I don’t think more than 90 seconds had passed since I’d given the order to cast off.

I looked back at the bridge as we pulled away, wondering if anyone had witnessed any of it. I noticed paint scraped off the edge of the lower bridge girder over a 2- to 3-foot area where we’d hit. Terri and I exchanged meaningful looks before she went forward, completed coiling and stowing the bow line, and pulled in the fenders on her way back to the cockpit. I sat in the cockpit, watching our new course down the river, willing my heart rate to drop back below 150 beats per minute.

I punched on the autohelm, took a final glance back at the bridge, coiled and stowed the stern line, and began reflecting on the chain of events that had nearly led to disaster. When Terri returned to the cockpit, she spoke in a measured tone. “We are not going to talk about this now, but we are going to talk about this later.” Then, she went below and put the kettle on.

We continued down the Piscataqua River. “Later” came in about 10 minutes, when Terri emerged from the companionway with two cups of coffee. We had a good long hug before we talked. First, we congratulated each other on not panicking and on taking our one chance at salvation when it appeared. Over the next hour or so, we reconstructed the entire event, from beginning to end, to determine the various decisions and actions and to consider what we should have done differently.

Although the fault and sequence of poor decisions that led to the near disaster clearly rested with me, Terri graciously never once mentioned that fact, accused me of being a complete idiot, or threatened to jump ship. She helped me to focus on the root-cause analysis of the event and to summarize the lessons learned.

At the mouth of the Piscataqua, we turned south into the Bigelow Bight and motor-sailed in light winds down the coast to Newburyport, without any further excitement. We got over the bar in a very light easterly breeze and a favorable tidal current, and then turned up the Merrimack River and picked up a mooring ball in town just after 12:30.

After a 37-year career as a project engineer and manager in the offshore oil industry, Hal Wells, along with his wife, Terri, commenced a “sabbatical of indeterminate length” (aka SaIL) in mid-2012. They chartered in Greece, Turkey, and the Pacific Northwest before buying their 2006 Beneteau 423 c’est le bon in late 2011. She now lives in Anacortes, Washington, from which they are exploring the Pacific Northwest. Hal recently completed a transatlantic delivering a Discovery 55 as watch leader and has earned ASA certification as a sailing instructor for levels 101, 103, and 104.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com