What the numbers can tell you about boat performance, comfort, and stability

Issue 151: July/Aug 2023

Yacht designers make many calculations in their work that help define the final shape and performance of the boat. Here we’ll explain the D/L and SA/D ratios and two numbers that we typically list in our used boat review specifications.

Displacement/Length Ratio

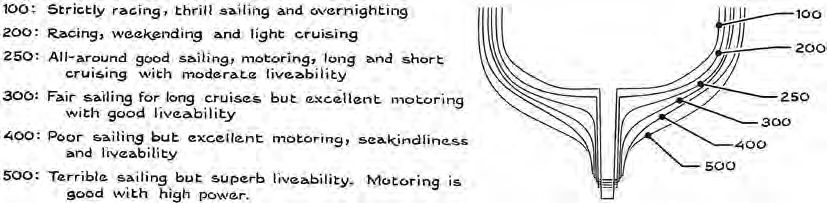

In very general terms, we know that the term heavy displacement means slow, and light displacement means fast. More precisely, the calculated displacement/length (D/L) ratio tells much more about the shape of the boat. Among other features, a heavy displacement hull form has slack bilges (a gentle turn where the hull meets the keel) and the light displacement boat has firm bilges (a sharp turn where the hull bottom meets the keel).

The displacement-length ratio (D/L) is a nondimensional computation that allows one to compare the relative heaviness of one boat to another, taking into account load waterline length (LWL) in feet. It is calculated by dividing a boat’s displacement in long tons (2,240 pounds) by .01 LWL cubed, or Dt/(.01 LWL)³.

Ultralight: under 100. Light: 100-200. Moderate: 200-300. Heavy: 300-400.

Sail Area/Displacement Ratio

The SA/D lets one compare the relative sail power of different boats. Here’s the formula: SA/D.667. SA is in square feet and D is in cubic feet to the 2/3 power. Displacement in pounds is divided by 64 to determine cubic feet.

Motorsailers generally have a number of or below 15. Coastal cruisers typically rate 16-17. Racers are higher, of course.

Comfort Ratio

In his book Understanding Boat Design (highly recommended reading for everyone), yacht designer and former Good Old Boat contributor Ted Brewer wrote that he “dreamed up” the comfort ratio “tongue in cheek,” only to find it “accepted by many as a measure of the motion comfort of a boat … it is based on the fact that the quickness of motion or corkiness of a hull in a choppy sea is what causes discomfort and seasickness.”

Here’s the formula: displacement ÷ 65 x (.7 LWL + .3 LOA) x beam 1.33, where displacement is expressed in pounds, and load waterline length and length overall are expressed in feet. Brewer said that heavy oceangoing cruisers rate more favorably in the 50-60 range, while lightweight boats may rate as low as 10 or less. Average cruisers rate in the mid-30s.

Capsize Screening Formula

The most accurate determination of a given boat’s stability is obtained by having it measured for one of the common rating rules. For example, the Offshore Racing Congress (ORC) employs the International Measurement System (IMS) that uses a computer-based program to determine, among other things, a stability index. Many expert sailors recommend a stability index number of 120 or higher for safe offshore sailing.

But because this program is not available to the average sailor who doesn’t care about racing yet still wants to know how safe their boat is offshore — that is, its ability to resist capsize and remain in an inverted position — the capsize screen formula was invented. It’s fairly simple.

Take the cube root of displacement volume (divide displacement in pounds by 64) and divide it into maximum beam (Bmax) in feet. For example, take a boat that displaces 15,000 pounds and has a beam of 11 feet. 15,000/64 = 234. The cube root of 234 is 6.16. Divide 11 by 6.16 and the result is 1.78.

Boats that rate 2.0 or less are considered more safe offshore than boats that rate more than 2.0. This simple formula has been often criticized as an oversimplification of the factors that determine stability and safety.

Dan Spurr is Good Old Boat’s boat review editor. He’s also the author of several books on boat ownership, among them Heart of Glass, a history of fiberglass boatbuilding, and the memoir Steered by the Falling Stars.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com