Mid refit in Ken’s yard.

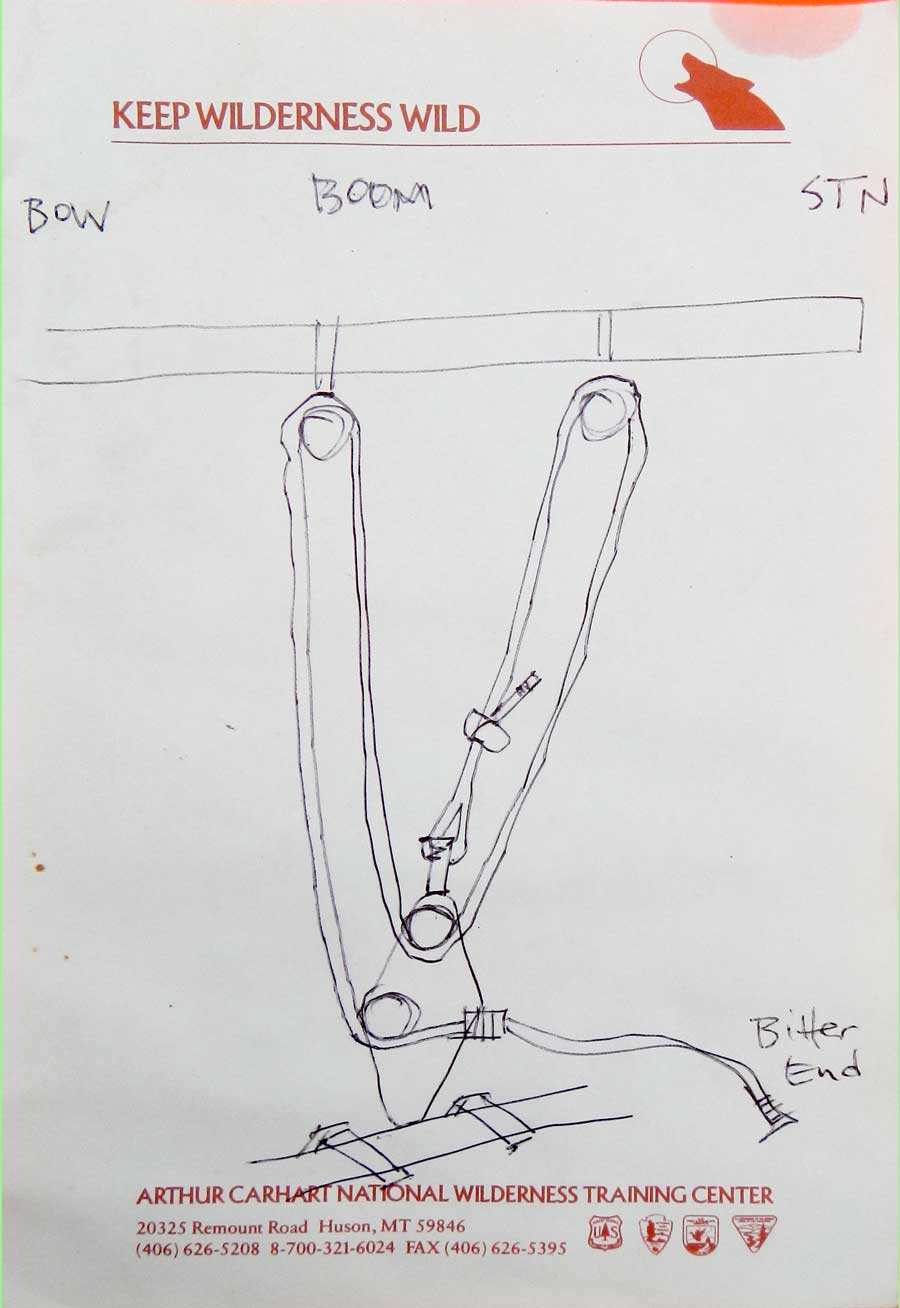

Keyhara was an old boat when my friend Mike and I found her sitting on a cradle in a backyard in Bay Village, Ohio in 1977. She needed a lot of work. The 23-foot cypress-hulled sloop had, at some point, apparently sunk at the dock. The transom was damaged, the boomkin was missing and the engine was frozen. The fuel tank was full of sludge and there was a spongy rib just aft of the engine mount and a couple of cracked stringers. Someone had caulked the hull with epoxy, which was spitting out from between the planks.

Of course, we bought her for $800. We hauled the boat to my folk’s house in Avon Lake for a refit where Dad fixed the transom, fashioned a new boomkin, and replaced the rib and stringers. With the help of a mechanic friend, he got the engine running. Mike and I re-caulked, sanded and painted the hull. We stripped the ugly green paint from the cabin and cockpit coaming and applied fresh coats of varnish.

When we purchased the boat, the title showed that she was built in 1935 and the make was listed as “Nimphius.” I had not heard of this make, so I never paid much attention to it. The name on the boat’s transom, however, appeared to be Orgy II. No one with any class would name a boat something like that, so we renamed her Keyhara. The name came from a horse that had won us a few bucks in one of the pre-Kentucky Derby races. Keyhara had a touch of the romantic to it and had already proved to be a lucky name.

She was ready to splash in June 1978 and we had her hauled to Rocky River (west of Cleveland) and lifted into the water. We kept her in the slings as long as we could, but after several hours it was sink or swim. The water rushed in through the seams in the hull and we pumped and bailed for hours to avoid sinking (this would become a yearly ritual with this boat). After a couple of days, the hull planks were swollen tight. Keyhara was ready to sail—albeit with the usual two or three inches of water sloshing in the bilge below the floorboards.

Keyhara in the slings at the old Sea Shell Marina on Rocky River.

Mike and I day-sailed Keyhara the summer of 1978 before crossing Lake Erie from Rocky River to Rondeau Bay, Canada on a gray day with mostly light winds. We spent a couple of days checking out the bay and the fishing town of Erieau, then, with our funds depleted, it was time to head home. We were up at about sunrise and put a reef in the large mainsail before heading out into a big southwest wind.

The waves built quickly. We could see them coming, bigger than the general 3 to 5 footers, gray-green and steep-sided…ominous. We pushed hard on the tiller to head up and take these waves on the nose. Yet not directly on the nose because they might stop us dead, and leave us without steering for the following set of waves.

Ken at Keyhara’s helm.

At the time, we were only a couple miles out and considered turning back, but we decided to go on. We needed to sail Keyhara, just as we had sailed our first small boats, nosing into the big waves when they came. Keyhara had a large open cockpit with only a partial bulkhead between the cockpit and the cabin. If we had turned back, we’d have had following seas, and a big wave over the transom could have been a disaster in those conditions.

Continuing on our course due south, we felt some mix of fear and exhilaration…like the roller coaster before you take the plunge. When the big ones came I would head up and hold my breath, watch the bow rise to the wave and crest it, spray flying. I call it spray, but it really felt more like someone throwing a gallon of water in your face. The water felt warm, I remember. We tried to miss the breaking waves but couldn’t always do it, and when we hit a breaker, the boat would shudder—a reminder to tend to your steering and avoid this punishment where possible.

It’s about a 10-hour sail across Lake Erie between these points and after an hour or so, we found our groove, getting used to the conditions and how the boat was handling them. The deeper water (40+ feet) offshore helped moderate the size and steepness of the waves. And though the day had started overcast, the sun broke through partial clouds as we sailed through the middle of the lake. Mike and I were in high spirits—finishing our first sail across Lake Erie.

Mike steers across Lake Erie.

There was another test on the way, however. As we pressed onward, the sky in the west showed a dark line at the horizon that developed into black storm clouds as a cold front approached. We could hear the thunder a long way off and it looked like it would get to us before we made the south shore.

Lines of thunderstorms on a lake like Erie should not be taken lightly. Unlike the widely scattered thunderstorms, which are part of the normal forecast for a summer afternoon, the “lines” can stretch the entire breadth of the lake, so you are probably not going to miss them. They also define frontal boundaries, which can mean big wind and a wind shift.

Just before the storm hit we pulled down the sails and started the Atomic 4. There was a blast of colder air just ahead of the rain and lightning. We tried, as best we could, to keep our distance from the wire rigging. The rain came in sheets and we were soaked through our foul-weather gear, which consisted of a windbreaker underneath a life jacket. The storm was violent, but it passed quickly and we were thankful for that. The voyage was a success.

Motoring into the storm with the sails down.

Since this sail with Mike, I have crossed Lake Erie many times, but that first one was something special. Mike moved to the San Francisco Bay area later that year and I stayed in Cleveland. But we’d made our memories together on an old boat past her prime. Encountering storms on a treacherous lake, and a couple of day sailors on their first cruise is not the way I would plan it today. Of course, most boaters will have a story like this because sooner or later you’ll get caught in weather, and have to deal with it. Just remember how you sailed that little centerboard boat. The same principles apply.

Years later, via the internet, I found that Keyhara’s builder’s name was Ferdinand “Red” Nimphius [1909-1999]).

“In the rolling dairy country of central Wisconsin, there’s a 200-acre farm that builds boats. Wooden boats.

There is a sign in his shop that reads ‘Every job is a self-portrait of the person who did it. Autograph your work with excellence.’

Nimphius is old-fashioned in his ways. He never studied naval architecture, but designs most of the boats that he builds. He goes for a simple, solid boat.”

(Excerpt from SAILING v. 25, n.8 April – 1991, pp. 104-105, 146.)

Photos by Mike Manente.