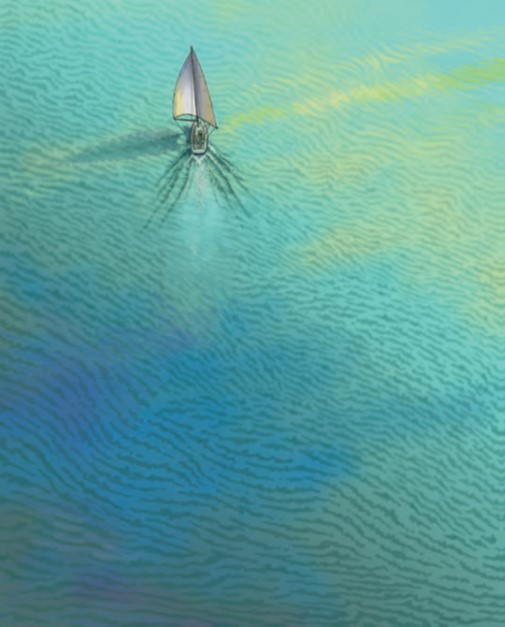

Our fleeting imprint on the water reminds us that now is what matters most.

Issue 140: Sept/Oct 2021

Paul’s wet shoes left a trail on the wooden dock, but it wouldn’t last long. Water trails never do.

I can’t for the life of me think how he got his shoes wet, but he did, and they made squishy sounds as he walked up the dock and toward the car. We’d had a lovely sail aboard my Tartan 27, Petrel, and Bubba, the recalcitrant Atomic 4, had behaved well.

Now with everything on the boat stowed neatly away, Paul and I were going home, no vestige left of our afternoon spree except Paul’s wet footprints on the dock. A casual glance would suggest that little Petrel hadn’t so much as moved all day. Her own tracks were long gone.

I think that’s one of the most mysterious aspects of being on the water. We leave no marks. We come, we go, we plow up a mighty wake or leave barely a ripple; no matter, in a few minutes the water shows nothing of our passage. Deep water, anyway, where we aren’t stirring up the silt.

By contrast, wagons cut deep ruts in the soil. Out on the Great Plains they say you can still see the path left by the “prairie schooners” that moved west over a century ago. But for all the steamers and sailers that have traveled the seas, not even the barest hint of their voyage remains on the water’s surface.

We can make an educated guess as to where John Smith dipped his oars during his voyages of discovery in what was called the New World. But we can’t know more than that. As mercurial and moody as water can be—sometimes white-capped and furious, sometimes docile—it keeps its secrets. We look instead to old wharves now abandoned, or to boats rotting in the shallows, and we guess at what may have passed that way once, and when.

According to the gospel, Jesus walked on water and Peter joined him there. Neither of them left tracks, though their strides atop the waves left a strong enough impression in the minds of the witnesses. Sailors still wish for a pair of St. Peter’s shoes when the weather gets rough or they’re stuck on a boat at anchor and want to get ashore. I wonder if shoes like that would make squishy sloshy sounds on dry land, or leave wet traces on the wooden dock. In any case, chandleries ought to stock them.

We say that time flows like a river, shaping itself around us and weaving together our memories. We can’t see the minutes fly by, we only see the gray hairs and wrinkles they leave behind—much like the old wharves and sunken boats at the river’s edge. Time and rivers, then, go companionably along, wrapping the earth like so many invisible ribbons. Was there really a yesterday? How do we know? We might have a passel of photos, to be sure, but a photograph is something we glance at; it may suggest a moment in time, but in fact, its only reality exists in the act of someone’s looking. It really captures nothing but our attention.

I think it’s the now of being on the water that keeps many of us so passionately tied to the prospect of setting sail—its profound disdain for purpose draws us in.

It may be that the very absence of our footprints keeps us in the present tense when we’re afloat. Now is all that has been or can ever be. And perhaps that’s the ultimate allure of the water.

So, let’s go sailing.

Now.

Janie Meneely was born and raised on, in, and around the Chesapeake Bay. She worked for years at Chesapeake Bay Magazine, putting in the commas and adding her own two bits to the editorial now and then. Happily retired, she has taken to writing songs about Bay history, people, and places. Seawater makes the best ink, she says; Bay winds write the best tunes. janiemeneely.com.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com