A flying sail on a furler can be hoisted at the dock before the day’s adventure begins.

Tips for sailing with a top-down furling spinnaker

In Part 1 of this article, in the January 2019 issue, Hugh introduced flying-sail furlers and described how he installed a top-down furler for his gennaker. In Part 2, he offers tips and techniques he’s found help him get the most fun out of the sail.

For me, putting my gennaker on a top-down furler brought the fun back into sailing under colored sails. It made setting and dousing the sail safer, gave me a safe way to jibe the sail, and let me sail my Viking 33, Hagar, comfortably with a small crew. I’ve since developed ways to handle the sail, from setting it, through tacking and jibing and dealing with a variety of wind conditions, to dousing it.

To obtain the best trim in a spinnaker, ease the sheet until the luff just begins to curl then sheet back in until the curl just disappears.

Hoisting

The beauty of a furled fun sail, as distinct from a free-flying spinnaker or one in a sock, is that it can be hoisted at the dock or at anchor so it’s ready for use when desired. And it can be furled under way and lowered once the boat is back at the dock.

Hoisting a furled flying sail is a simple matter and can be done even on the windward side: attach the halyard, and the tack, lead the sheets according to how you plan on jibing (see page 27), and haul it up.

Easing the sheet too much will cause the sail to collapse.

Setting

When it comes time to set a furled spinnaker, it helps to first furl the jib, so as not to blanket the spinnaker and to allow you to watch it as it unfurls. Bring the boat to a point of sail where the apparent wind will fill the sail as it unfurls, and watch the bottom of the sail to make sure it is filling. This is important, because if the sailcloth in the bottom third of the sail collapses while it’s being unrolled and gets near the cable while it’s turning, the cable can grab the sail and start rolling up the bottom the wrong way. This “backwrap” can be confounding. Unroll the top and the bottom tightens — unroll the bottom and the top tightens.

The way to avoid backwrap is, once the sail starts unrolling, to “blow/fly” the bottom of the sail to keep it away from the cable. Don’t just pop the furling line. Pull the sheet and let the sail unroll like a jib, but maintain tension on the furling line to keep the unrolling sail under control. When it does backwrap, stop and roll the furler drum the other way until it undoes itself. Blow/fly the bottom of the sail again and continue to unfurl it. (One manufacturer provides plastic rollerballs that go over the cable to defeat the backwrap challenge.)

Once the sail is unfurled, trim it as you would a really big jib. Ease the working sheet until the luff of the spinnaker curls a bit, then pull the sheet back in until it stops curling. It’s the same process as easing the main or jib until it bubbles at the luff and sheeting it in until it stops. The difference with a top-down furler is that the luff of the sail will not be supported. There will be a torque cable, but that will not get in the way of the sail.

Start with the helm

One of the joys of sailing a spinnaker tacked at the bow, whether it’s on a furler or not, is that you can cleat the sheet and drive the boat under the spinnaker to maintain trim. Steer up to windward to curl the luff a bit, then head downwind to keep the luff where it’s just starting to curl.

No flying sail attached at the bow will like deep sailing angles that are close to dead downwind; it will often collapse as it is blanketed by the main. You’ll get to your destination faster by sailing at a “hotter angle” on one tack, and then sailing a similar angle on the other tack.

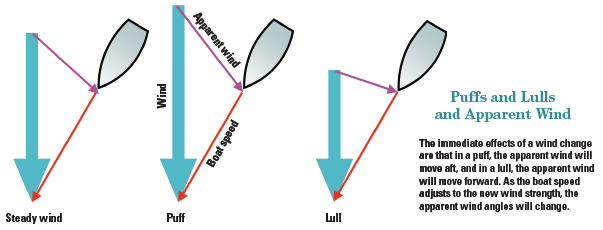

When you are sailing at these jibe angles instead of dead downwind, puffs and lulls will be important, as they change the apparent wind. The apparent wind shifts aft in puffs and forward in lulls. Respond to these changes in wind pressure, and their effect on apparent wind, by using the helm to control the sail — head up in puffs and down in lulls. In lighter air, don’t be too shy with the helm.

If the spinnaker does collapse when you sail too low, it may make a fair amount of noise, and the boat will lose speed. Sheet in the spinnaker and drive the boat up to a hotter angle to refill it. As the boat gains speed again, the apparent wind will shift forward and you can drive the boat back down to a lower angle. As you gain experience, you will get better and better at keeping your flying sail pulling.

I have lots of fun sailing my furling spinnaker this way. It’s definitely a great way to go when shorthanded, as it’s much easier to steer the boat to keep the sail drawing than it is to be sheeting the sail in and out for hours on end. When I want a break from helming, I engage my autopilot and over-sheet the sail a little so it remains stable in the puffs and lulls. If I really want to relax, I use the autopilot controls to make course adjustments as needed to keep the sail drawing.

When the tack line moves to windward, head up.

Playing the angles

So how do you know when your boat is sailing at its optimum jibe angle?

One way is to buy or develop a set of polar diagrams or tables that show how fast your boat should sail at different apparent- and true-wind speeds and angles and sail the boat to match the polars. This works best with good wind- speed and wind-angle instruments that have easy-to-read big numbers. This is my least favorite way to sail, as it forces me to keep my eyes in the boat rather than on the sails.

Another way is to look for pressure on the spinnaker sheet. When the pressure on the sheet eases, head up to a hotter angle. As the boat builds speed, head down again and see how deep it will sail with sustained speed and pressure on the sheet.

Adjusting the height of the tack provides another way to determine the best jibe angle. Easing the tack line a foot or two will let the tack move to windward or leeward of the bowsprit. Watch it from the helm. When the tack line points to leeward, steer to leeward to bring the tack to the centerline. When the tack line points to windward, steer to windward. (This method may not work in very light wind if the tack falls under the weight of the sail.)

Easing the tack line when heading downwind allows more of the spinnaker’s luff to project away from the mainsail.

In some systems, the tack line is attached to the bottom of the furling drum, so when the tack line is eased, the furling drum rises and the torque cable slackens. In other systems, the tack line is led through a sheave on top of the drum, so the drum remains fixed to the boat and the cable remains taut.

When the tack line moves to leeward, head down.

When the wind pipes up

Pressure on the helm will tell you if you have too much sail up. It’s best to take action before the sails overwhelm the helm.

First off, learn through experience when your boat gets twitchy with the spinnaker set, so you know to douse it before the dreaded wipeout. This is where a furler really shines.

When you want to shorten sail, head downwind until the pressure on the sheet unloads and roll up the spinnaker. Nobody has to go to the foredeck and there is nothing to dump in the water. I’ve found that 15 knots of wind is a good “line in the sand” for my boat as the wind speed builds.

To handle a big puff, try easing the mainsheet first, then dump air from the spinnaker by easing the sheet if necessary.

If when sailing under a furling spinnaker and a big puff hits, the boat is heeling too much, and the helm is too hard, the usual first step is to ease the boom vang. This will spill air by twisting off the top of the mainsail, and works especially well with a large mainsail (sprit boats in particular often use the vang first).

If easing the vang is not enough, ease the mainsheet and then, if necessary, ease the spinnaker sheet. If the stronger wind persists, regain control of the sail by heading down to take pressure off the sheet and the sail by moving the apparent wind aft.

The tack line straight up and down, above, is a good sign the boat is sailing downwind at maximum velocity made good (max VMG).

Reaching

Another joy of flying sails is how they power the boat when reaching. The hotter angle brings the apparent wind forward and the boat really gets going. Reaching at true-wind angles of 90 degrees or better can be a blast.

When reaching, tighten the tack line to close the leech as much as possible. Cleat the sheet, and either drive the boat to follow the sail or trim the sail to maintain a heading.

Putting telltales on the spinnaker and using them in the same way as on a jib helps when trimming the sail on a reach, but works best on a flatter spinnaker cut for reaching.

If the boat broaches, the flying sail will flap and make lots of noise, but it’s just noise. When the pressure is off the sail, ease the sheet and steer the boat downwind to restore order.

A genoa will perform better than a flying sail at closer angles to the wind, but if you are not racing, you might want to enjoy the ride even if the boat is a bit slower.

The top-down furling spinnaker really struts its stuff on reaching points of sail.

Jibing

There are two ways to jibe a top-down furling flying sail: inside the torque cable and outside the headstay, or outside both. Each method requires the sheet to be led in a different way, so decide which you will use before rigging the sail.

Inside jibe: Steer downwind to collapse the spinnaker

Inside jibe –Lead the working sheet from the turning block to the clew as for a jib, then run the lazy sheet to the clew through the gap between the headstay and the torque cable. The lazy sheet is on the inside of the sail just like the lazy sheet on a jib, but it goes outside the headstay.

To perform an inside jibe, first make sure your sheets are clear and will not snag, then:

Steer downwind to stall the kite behind the mainsail while easing the sheet to unload the sail.

Jibe the main at any time but stay downwind, as blanketing the spinnaker will work in your favor.

It helps to have a crewmember forward to haul on the new sheet and pull the clew through the gap between the headstay and the cable.

While holding the boat close to dead downwind, keep pulling on the sheet (there’s a ton of line) until the spinnaker is through the gap. When the clew is at least back to the shrouds, head up and fill the spinnaker while continuing to sheet it in.

pull the clew between the headstay and the cable

Outside jibe –Run the lazy sheet outside the torque cable and the furled spinnaker before attaching it to the clew. Because the sheet is outside the sail and the cable, it can drop down and slip over the top of the bowsprit and under it, which is something to avoid.

Set the lazy sheet so that it’s above the furling drum and does not have a lot of slack in it. The goal is to avoid the sheet becoming snagged below the furler or dropping below the bowsprit and making its way under the boat.

Head downwind but do not stall the spinnaker.

Ease the working sheet to get the clew as far forward as it will go with wind still in the sail. At the same time, pull the slack out of what will become the new working sheet to keep it from dropping down.

and haul it toward the shrouds.

Jibe the main, but stay downwind so the main blankets the spinnaker, then haul on the new working sheet and pull the clew of the sail around the cable outside of everything. There is a lot of sheet to bring in.

Once the clew of the spinnaker is around the cable and back to the shrouds on the new tack, head up and fill the sail.

Some sails come with a batten on which to rest the lazy sheet so it does not go under the boat during an outside jibe. You can rig your own batten using rigging tape.

The outside jibe is definitely the easier one to perform in stronger winds. It’s also the better choice if the flying-sail furler is close to the headstay and leaves little room for the spinnaker to pass between it and the cable.

When I first began using my flying furler, I used the outside jibe, as some talented professionals recommend it and I thought it would be easier. After a few snags under the furler unit and a few submarined lazy sheets, I switched to inside jibes. I find that the apparent wind on an outside jibe is insufficient to blow the spinnaker far enough forward, and I have not been able to get the timing just right.

Handling unplanned events

- The spinnaker does not make it around before it starts to fill: Jibe back to your original point of sail, refill the spinnaker, and try again.

- The spinnaker hourglasses: Lower the halyard 4 or 5 feet to free the top swivel and pull the hourglass out with the sheet.

- The lazy sheet goes under the boat before the jibe: Retrieve the sheet, relead it, and reposition it before starting the jibe.

- The new lazy sheet goes under the boat during the jibe: Complete the jibe, then grab the offending sheet at the clew witha boathook, pull it all the way through, and rerig it.

- The spinnaker wraps around the top of the headstay: The halyard is rigged wrongly. Jibe back, roll up the spinnaker, drop it, and rerig.

Inside jibe: Jibe the mainsail at any time but keep heading downwind so it blankets the spinnaker.

The chicken jibe

If you don’t want to jibe your spinnaker while it’s flying, simply roll it up, jibe the main, and unroll the spinnaker on the new tack. Or drop the sail to the deck after rolling it up and relaunch it on the other side after jibing to your new course — this method works when the clearance at the top of the rig is poor and you want to avoid having a halyard bending over the forestay under pressure on the new tack.

Head up to the desired course and trim the sails accordingly.

Small crew, no problem

Most of our sailing in North America is in moderate to lighter air when a spinnaker can make it a lot more fun. A furling flying sail makes this possible without the need for a large crew to handle it.

We even use our furled spinnaker for around-the-cans racing. We don’t beat the best boats out there, but we are in the mix with half the crew and less experience in the boat. When we go daysailing, the spinnaker is often the first choice of sails to rig for a great day on the water. Our furling kite has even earned its local nickname “the Awning,” all in good fun.

Thoughts on Spinnaker Choices

The best sail for any individual sailor is the one that works best in the prevailing winds where he or she sails and gives the best balance between performance, cost, and ease of handling.

Not all asymmetrical sails are cut the same. An A2 spinnaker is designed for running while an A3 sail is better for reaching, as it is flatter. A Code Zero, with its very flat shape, is best for reaching at closer wind angles.

An A2 runner may not furl as well as an A3.The tighter leech on an A3 can make it easier to deploy.

A Code Zero can be the easiest to furl because the cable is inside the sail; however, it does not perform as well downwind, and it needs stronger gear due to the higher loads imposed by upwind sailing.

If I were buying new, was cruising, and could have only one spinnaker, I think I might go for a Code Zero. Since I was buying used and do some windward-leeward around-the-cans racing, I chose an A2 that is a bit on the shy side for my boat.