Trying to undo them exposes their stubborn side

Issue 125: March/April 2019

The title of Henry James’ classic novel The Turn of the Screw is a metaphor for the stress felt by a governess in her struggles with resident ghosts, but for those of us who work with screws, it’s the unscrewing that’s often our undoing.

Every sailor has a maddening screw story. Screws are devious and conniving little creatures that, in collusion with their ham-fisted installers, are virtually guaranteed to make trouble for boat owners who struggle to free them. Sometimes they spin right out and we smile, but often they punish us by stripping, seizing, galling, or simply refusing to budge.

Somewhere within the most difficult-to-reach spot of your boat lurks a group of screws that must be removed. They will get progressively more intractable as you twist, until the last, which steadfastly will not yield. And there you are in the dark with bloodied knuckles, covered in sweat, shouting at an inanimate object, “You little [choice epithet], why won’t you come off?”

And is there a boat on the planet that doesn’t contain “spare” screws in the lower reaches, dropped there over time by poor souls attempting to do a two-handed installation with one hand?

Screws have been with us for a long time. The ancient Greeks used them in olive and grape presses, and Archimedes adapted them for irrigation. In Europe they were handmade by skilled craftsmen, mostly for furniture or weapons; each was unique, expensive, and sold individually.

The Industrial Revolution in England changed all that. After the invention of the cutting lathe by the Wyatt brothers in 1760, the screw could be produced precisely, quickly, and cheaply. Hence the rise of the machines. When steam engines were installed in ships in the 19th century, screws replaced nails, because they performed much better with the constant vibration, and they have been the marine fastener of choice ever since.

It’s all in the head

Marine threaded fasteners generally come in three flavors: machine, self- tapping, and wood/sheet-metal screws. On a boat, the heads of these screws are primarily either slotted or Phillips.

The bane of boaters and technicians everywhere is the cursed slotted screw. In use for centuries as it was the cheapest and easiest to make, its presence is usually indicative of an older boat. You can only remove older screws subject to corrosion, seizing, or galling, by pushing down hard and torquing with all your might. If you’re not careful, the flat-bladed screwdriver will “cam out” and strip the head, making the screw insanely difficult to remove and your day much more interesting.

American screw manufacturers spent decades attempting to solve the shortcomings of the slotted screw. Patents were awarded on all sorts of screw-holding gadgets, but none were effective. And the deeper the slot stamped in the head, the weaker the head became and the more likely to break or strip.

In 1909, Canadian inventor Peter Robertson was awarded a patent on a socket-head screw that had a square recess with chamfered edges. Eureka! Its square-headed driver fit tightly and didn’t cam out. Fisher Body loved it, became a big customer, and in 1913 Robertson went all in on production. But during World War I it failed to catch on in Europe or America, and the Robertson screw was scarcely sold outside of Canada. Today it’s known as the deck screw and is used primarily in construction.

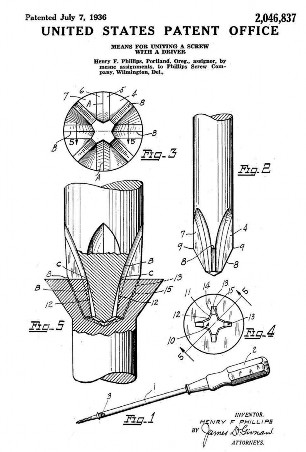

Enter Henry Phillips of Portland, Oregon, an inventor and salesman who incorporated a new shape, a cruciform, into the socket of the screw. It was, he said, “the biggest little invention of the 20th century — particularly adapted for firm engagement with . . . a driving tool.” Learning from Robertson’s mistakes, he moved to license, not manufacture, his screw.

He was then abruptly rejected by all the major screw manufacturers, who basically said that the new design did not promise enough commercial success.

But, like a seized deck fastener, Phillips was a stubborn man and persevered. His screw was particularly suited to power-driven operations, and the American Screw Company convinced General Motors to use the new screw in the 1936 Cadillac. The new design saved time and money, and by 1939 most American screw manufacturers were producing what we now call the Phillips screw. And it was such a hit that one boatbuilder wrote that, by using the Phillips screw, its workers saved up to 60 percent of their time.

During World War II, the screw became the industry standard, and by the 1960s when its patent expired, it was being made in 240 factories worldwide.

But . . . regardless of design, screws on boats are destined to get stuck and often can be removed only with resort to chemical solutions like PB B’laster, CRC Freeze-Off, Liquid Wrench, or, as a last resort, a drill. And after many frustrating turns of my screws, I finally learned to apply anti-seize lubricant before reinstalling the fastener, and to refrain from yelling at stuck fasteners — they’re just not listening.

Robert Beringer is a Florida-based freelance marine journalist and photographer and a member of Boating Writers International. He learned to sail on the Great Lakes in a Hobie 16, holds a USCG 50-ton master’s license, and has logged more than 28,000 miles under sail. His first book, Water Power!, a collection of marine short stories, is available at Barnes & Noble.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com