Relying on celestial navigation and a very good old boat, Bert ter Hart solos the globe.

Issue 137: March/April 2021

When Bert ter Hart bought his OCY 45, he had an inkling that down the road, she might be the boat to take him on a leisurely, tradewinds cruise across the Pacific, maybe farther. But into the record books? That wasn’t even a notion 13 years ago.

Yet, on July 18, 2020, the 61-year-old joined an extremely small and rarified group of sailors. On that day, Bert returned to his home of Gabriola Island, British Columbia, after 267 days alone at sea, tying the knot on a 28,860-mile circumnavigation. And while many others have sailed around the world, even solo, Bert is the first documented North American to do so nonstop via the five capes using only the traditional tools of celestial navigation.

Why had he done it the hard way? His motivations were both straightforward and multi-layered—somewhat a reflection of the sailor himself—and boiled down to a pretty basic philosophy he wanted to test: There’s really no reason for not fulfilling one’s goals.

“It wasn’t some lifelong dream. I thought of doing this relatively recently. Which is proof in the pudding that you can hatch one of these ideas and realize it within a relatively short time. And it doesn’t matter how old you are; you can have these dreams and realize them,” Bert says. “I wanted to motivate anyone of any age to step out their front door and seek adventure where they can find it and keep those dreams alive.”

More than 28,000 miles of trackless ocean is a long stretch from Saskatchewan, where Bert grew up, the son of Dutch parents. Yet the seeds of what would be his record-breaking adventure at sea were sown in this northern prairie country. His father, who had circumnavigated with the Dutch merchant marine after World War II, went on to become a land surveyor in Canada. He introduced Bert to sailing on a local reservoir, starting with Lasers, Hobie Cats, and windsurfers. He also took him surveying, instilling in Bert a lifelong fascination with early explorers, charting, maps, and the elegant mathematics and tools of surveying and, by extension, celestial navigation.

At 17, Bert entered Royal Roads Military College near Victoria, BC, where he planned to join the Navy and study physics and physical oceanography. Hopes of the former were dashed when he learned he was nearly entirely color blind; the Army it would be. The nine years he spent there—finishing his career as a platoon commander in the Canadian Special Forces—sharpened in him a focus, discipline, and mental and physical toughness that would serve him well years later while circumnavigating.

His post-Army career opportunities took him to Los Angeles, where, between helping develop and launch a successful health care software company, he started crewing on keelboats.

“I could suffer for a long time as rail meat,” he says. “I was basically just crew, but it was still experience. It doesn’t matter what boat you get on or how you’re sailing— if you keep your eyes open, you can gain experience. I don’t have a racing background, but I learned a lot about racing. I watched how they would push the boat, learned what was and wasn’t important to make a boat go fast.”

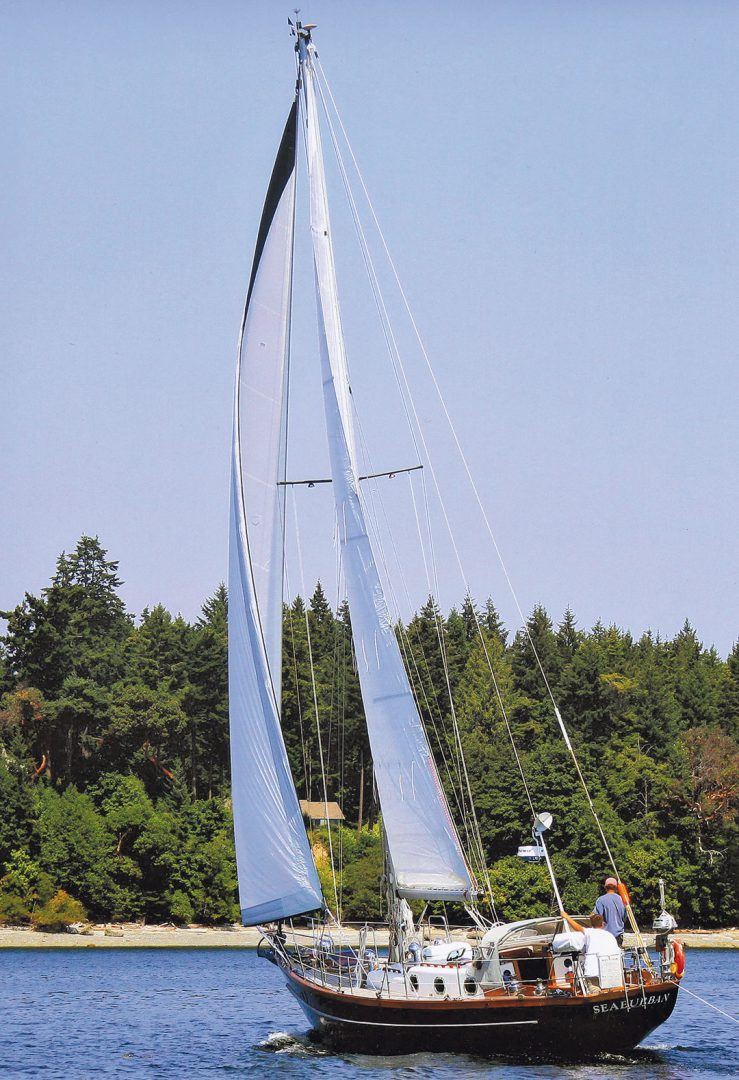

Eventually, he returned to Vancouver and started looking for a boat that could take his family cruising and sailing in the waters between Vancouver and Alaska. In 2007, Bert found Seaburban, a 1987 Reliance 44 hull designed and built by Pierre Meunier in Montréal and finished by Ocean Cruising Yachts (OCY) in Hamilton, Ontario. Her second owner had thoroughly kitted her out.

“I was lucky to get the boat because the bones are very good,” he says. At 45 feet overall, she’s 31.5 on the waterline, and only 11.8 feet wide, with a 6.2-foot draft. “It’s a very narrow boat with long overhangs and a cutaway forefoot. It looks like an Alberg that’s just been stretched. It was built professionally and maintained professionally. And it had everything under the sun on it.”

Years of sailing challenging waters followed. When eventually he conceived the plan to solo circumnavigate, Bert had sailed about 18,000 miles on Seaburban, including to the Bering Sea, through the Aleutian Islands and Haida Gwaii, and up and down British Columbia.

All the while, he fed his sense of history and connection to the great navigators who had explored these waters.

“One of the things I’ve done sailing up and down the west coast of North America is I’ve retraced most of the places that Cook and Vancouver have been,” Bert says. “You can still go to, say, Bligh Cove, and look at the trees that Bligh looked at when he was there. You can go to Nootka Sound and Friendly Cove and walk the same forest paths that Vancouver and Bligh and Cook walked, and all the First Nations people, because that place hasn’t changed much at all. There are not many places in the world where you can actually step directly into that environment and ecosystem. I am deeply interested in that.”

It was natural, then, for Bert to choose the navigation methods of early sailors to find his way around the world.

“I wanted to get a feeling of the experiences of those early navigators,” Bert says. “There’s nothing about sailing now that’s remotely connected, other than the act of sailing and the principles of it, to the people who first did it. But you can pick up a sextant, turn off the GPS, calculator, and iPad, all that kind of stuff, pick up the sextant, a piece of paper, the tables, and a watch, and have the exact same feeling that these guys would have had as to, ‘Where the hell am I?’ You can very closely and very intimately…mimic their world, that part of their ecosystem, using a sextant. You can’t do it any other way.”

While he pursued this fascination with historical exploration, he worked to learn his boat. When he began conceiving the idea of solo circumnavigating, those miles and experiences gave him the confidence and caution he needed to make the journey.

“I’ve been to 60 degrees North in that boat, which is pretty amazing. It’s demanding. So, I knew the boat pretty well in interesting conditions. I wouldn’t say severe conditions, given what I know now. But I had a pretty good idea of what the boat needed to do the trip around and be safe…I was pretty sure that the boat would get me out of pretty much any trouble I could get into as long as I wasn’t completely stupid about where I was going. I understood her strengths and limitations. So that’s one reason I sailed at 44 or 42 South rather than 47 South. I knew I didn’t want to be down there; I just felt it would be too much for the boat,” he says.

He also nailed down the fundamentals, basics that he believes are key to succeeding at anything.

“I knew I could reef the boat going downwind in 40-plus knots by dragging the sail down the shrouds. I knew how to heave to. I knew how to deploy this and retrieve that. When I left, I had the fundamentals of sailing my boat down pretty square. It wasn’t a mystery to me.”

The venerable Ocean Cruising Club agreed, naming Bert ter Hart one of the first two recipients of its inaugural OCC Challenge Adventure Grant in 2019.

He was on track to leave in late September, after an eight-week shakedown cruise to Alaska during which he tested the boat’s new standing and running rigging, among other upgrades. But one change he’d made—a new structural furling system for the Solent sail—didn’t work as he’d wanted. Back in Gabriola, just before he was to depart, he went up the rig to install a tang for a traditional roller-furling headstay for the Solent, and disaster struck. Drilling into the mast, his hole saw nicked the Amsteel spinnaker halyard that his ascender was attached to. The halyard snapped instantly, as did the line holding his Prusik backup.

“I rocketed down the forestay, I didn’t fall straight down. I managed to squeeze the foil— because there was no sail on it—between my upper arm and my ribcage, and I landed at the front of the boat,” he says. “To be perfectly honest, I should be dead. A fatal fall is anything above 15 feet, which is basically two stories, and I fell 55 feet, the equivalent of five stories.”

Airlifted to a trauma unit in Victoria, Bert learned he had fractured four ribs and collapsed a lung. But his internal organs, which could have been pulverized, were somehow intact, and he had never lost consciousness.

“The doctor said, ‘You should buy a lottery ticket; today’s your lucky day. There’s nothing wrong with you that we can see, and I don’t know how that’s possible,’ ’’ Bert says. “I walked out using my dad’s cane. The lung re-inflated gradually.”

About five weeks later, on October 26, 2019, Bert finally left Gabriola, still in pain and now behind schedule. Yet within days he pulled into San Francisco to resolve a fuel-tank issue and to replace a light-air vane that had disconnected from his Monitor self-steering. Rick Whiting, the OCC’s San Francisco port captain, helped arrange the 24-hour stop at Berkeley Marine Center in Oakland.

It turned out to be a highlight of the trip, Bert says, when solo sailor Randall Reeves—he of the Figure 8 Voyage—delivered the vanes “and a few other bits and pieces he thought necessary for the Monitor. He also delivered a bottle of bubbly that was only to be opened upon successfully doubling Cape Horn! Spending time with Randall was an unexpected bonus.”

Reenergized after the unscheduled pit stop, Bert was off again for that first momentous waypoint. He would round the Horn, then Cape Agulhas at the tip of South Africa, Cape Leeuwin at Australia, South East Cape at Tasmania, and finally South Cape at New Zealand.

During his voyage, Bert related his challenges, frustrations, victories, and some lyrical descriptions of the oceanic world at the5capes.com. Among the challenges he recounted were many more days of excruciating calms than he’d ever expected—far harder on the boat and the psyche than gales and storms. But he also gave plenty of ink to the rewards he experienced.

“For me, staring endlessly and mindlessly at the blue expanse that envelopes me, I am at peace,” he wrote in a blog entry en route to Cape Horn. “My mind is at rest and I wonder if I should be thinking big thoughts in some Thoreau-esque, Walden Pond way. Perhaps they will come. Perhaps not. The important thing is that I feel it doesn’t matter right now. And that, as trivial as it may sound now, seems a big thought. I realize I am living in the moment and just how hard that actually is.”

He devoted at least two to three hours a day to navigating, using only a sextant, tables, pencil, paper, and a watch. The experience only deepened his respect for the explorers he admired.

“One thing that struck me was how unbelievably competent those sailors were. I was basically sneaking around the world, I wanted to avoid as much trouble as possible and make it as easy as humanly possible, and hopefully Cape Horn doesn’t notice I’m there,” he says. “But those guys ranged around the Southern Ocean at will. They went wherever they wanted to, despite wind, weather, and wave.”

One advantage Bert did have over early explorers was weather forecasting. He carried an Iridium-Go SP that received GRIB files, which he interpreted using PredictWind. He stayed in communication with his neighbor, John Bullas, a former meteorologist for Canada’s weather service who volunteered to analyze weather data that Bert couldn’t access, warning him, for instance, of fast-forming dangers like weather bombs.

Bert also turned to renowned solo circumnavigator Tony Gooch, whom he had met briefly before leaving and who helped him apply for the OCC Adventure Challenge Grant.

“He’s an amazing sailor and a true gentleman,” Bert says. “Whenever I contacted him, he answered immediately, offered advice, routing suggestions, and general weather forecasts. I know he’s done the same for a number of sailors and especially those who belong to the OCC.”

After rounding Cape Horn, John alerted Bert to an especially ugly Southern Ocean hurricane, and Bert sailed Seaburban to Port Stanley, Falkland Islands, to wait out the weather at anchor (he didn’t go ashore). Ironically, that time at anchor was as close as Bert came to losing the boat; he’d only brought light anchor tackle to save weight, and he dragged dangerously for hours in high winds and vicious chop until finally, in desperation, he paid out his last emergency bit of rode—and it held.

As he sailed through the Southern Ocean toward Australia, he learned of the pandemic that was enveloping the world.

“I became aware of it early,” he says. “And what’s interesting about it is I never felt more useless in my life, because I’m in the middle of nowhere, I’m weeks away from everything, and even if I can get to Perth, a) they won’t have me, and, b) I can’t fly anywhere. There’s nothing I could do.”

He also had a more immediate worry; he was running out of food. He’d provisioned based on his previous voyages and on his research into how much other circumnavigators ate. But by the time he reached Cape Horn, he realized he wasn’t going to have enough food to fuel himself properly.

“To get back in nine months with what I had, I would be eating basically rice and oats and perhaps only a third of a cup each a day,” he says. “I underestimated my appetite.”

Bert started rationing, at one point getting down to as few as 800 calories a day, which he could feel diminishing his mental acuity and his physical strength. Concerns about food became sharper when, after rounding New Zealand, a massive storm forced him off his intended easterly track in the steady, strong winds of the Roaring 40s and farther north sooner than he’d planned. And, the halyard on his big genoa broke, leaving only the smaller Solent headsail. This slowed him down, adding an estimated two weeks to his slog upwind through the Pacific.

His sister Leah, without whom Bert says he probably wouldn’t have gotten off the dock let alone around the world, suggested a stop in Rarotonga, now more or less along the new, more northerly track, for emergency provisions.

Officials in the Cook Islands responded to the proposition with a flat no; the country was shut down due to the pandemic and wasn’t admitting foreign vessels. Leah persisted, and eventually they came up with a plan that wouldn’t violate their pandemic protocols, allowing Bert to take on provisions offshore with a health minister overseeing the interaction.

On July 12, with only about a week to go until landfall back home, Bert mused in his blog, “Where did the time go? It seems more dream than done. What on earth (literally) will I do with myself when there won’t be watches to stand, sails to tend, and courses to figure?”

Five days later, he and Seaburban came home.

“Who would have believed it a year ago?” he wrote. “I was barely able to dream it, let alone believe it.”

Good Old Boat Senior Editor Wendy Mitman Clarke is a lifelong sailor who documented the 1994-95 BOC Around the World Race for Smithsonian magazine. You can see more of her work at wendymitmanclarke.com.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com