On an ill-fated voyage home, a young family learns lessons in seamanship and community spirit

Issue 153: Nov/Dec 2023

All sailors start somewhere. As a teenager, I was infatuated with stories in National Geographic in the late 1960s of young Robin Lee Graham sailing singlehanded around the world in his tiny boat. I found building plans in Popular Mechanics and constructed a sailing dinghy out of cedar ribs and plywood. Like many, I taught myself to sail, reading about the fundamentals in magazines and books. Practical knowledge came from dodging oceangoing ships and tugboats in the Fraser River just south of Vancouver, British Columbia.

I was hooked, dreaming grandiose plans of a sailing future. Then life got in the way. Starting a family and career left very little time for recreation. Sailing took a distant back seat but was always there, waiting to return.

Years went by and eventually I convinced my wife, Carey, that a boat was in our family’s future. As a young mother, she was nervous on a commercial ferry, let alone a tiny sailboat. But she also thought anything would be better than the 2 a.m. visit to a campground outhouse. We began to explore possibilities.

The average cruising boat of the 1970s was exemplified by the ubiquitous Catalina 27 or more luxurious Catalina 30. But with a very limited budget, even the decadence of a Catalina 27 was far beyond our reach. Instead, we found a robin’s egg blue Balboa 20 sitting on a trailer in a yard with a faded “For Sale” sign taped to the bow. With sitting headroom in a cozy cabin, a portable toilet hidden under the V-berth, and a pressurized kerosene countertop stove, this was something we could afford.

The little boat wintered in our yard on its trailer, swing keel tucked up under her belly, while I tried to figure out how the mast was going to go up. We were brand new to sailing boats of this size and had no practical knowledge, but the promise of the great unknown was so tantalizing. Our budget didn’t allow for electronic navigational aids, and no sounder or knotmeter, or even a VHF radio, graced the little boat. But we were set for weekend cruising adventures in the Canadian Gulf Islands.

The Balboa 20 at anchor the day before the rudder failed, with young Nicky in the foreground.

On a mid-July day in 1980, we sailed from our home port in Ladner. It was 10 miles to the Sand Heads Lighthouse at the mouth of the mighty Fraser River and then 12 miles across the Strait of Georgia to Porlier Pass between Galiano and Valdes islands, one of the gateways to the Gulf Islands. This wasn’t our first sail across these open waters and we were feeling quite comfortable — experienced, even.

After a few days of cruising the fabled islands in brilliant sunshine and light winds, it was time to head back home. Although we usually anchored in quiet bays, we decided our last night in the islands was going to be spent in our first “destination marina” — the friendly Telegraph Harbour Marina on Thetis Island. Being young and new to boating, we were somewhat shy about mixing it up with big boat owners, our little blue boat almost invisible among the collection of white fiberglass. We had a great time, enjoying the grounds of the facilities, the ice cream in the cafe, and the extremely helpful and informative staff. Dinner was on the hibachi in the sunny cockpit. This kind of cruising was new to us, and we loved it.

The morning of our homeward passage dawned like all the previous mornings, bright and sunny, with a light westerly breeze rippling the water. With dividers and parallel rulers, I calculated a course across the exposed waters of the strait back to the mouth of the Fraser River. With a westerly breeze, it would be perfect for crossing. The current prediction at Porlier Pass called for a midmorning departure to catch the slack turning to flood. We untied the dock lines and were soon underway. I thought it curious that although many boaters were up and about, no one seemed in a hurry to leave.

Our trusty Chrysler outboard powered us through a narrow dredged channel between Thetis and Kuper (later renamed Penelakut) islands toward Porlier Pass a few miles away. We hoisted the mainsail as the westerly filled in, and the noisy Chrysler was banished to silence on the stern. The hanked-on jib soon followed as we sailed through Porlier at slack and out onto the strait. It looked like it would be a promising sail, far better than powering all the way home.

Stretching away from land into open water, the seas started getting boisterous and the breeze freshened, with whitecaps dotting the water ahead. On any given summer day, this area of Porlier Pass would see a plethora of aluminum car-toppers fishing nearby. But there was not another boat in sight. And it was a perfect day! The skies were blue and the sun was warm, with only a few low clouds to the west. On we sailed, full of confidence, the wind rising perceptibly.

Although the Balboa had a pulpit at the bow, there was no pushpit and no lifelines. In an abundance of caution, Carey took our 6-year-old daughter, Nicky, below. I figured it was more for her own peace of mind, since she was not a comfortable sailor. I was having a blast. The Titanic-style life jackets were on and I was confident in reaching across to the Sand Heads Lighthouse 12 miles away. I couldn’t see the beacon yet, but I recognized the background mountains on the horizon and knew where it should be. All was well as we started to surf down some of the larger waves.

Suddenly, as we swooped down a wave, the rudder failed to respond. I glanced back at the transom to see the bottom half of the rudder trailing on the surface. Yikes! A quick peek over the stern showed that the fiberglass skin on one side of the rudder had failed, with the skin on the opposite side just barely hanging on. The little boat slid to leeward and the boom slammed over in a jibe. We were out of control. I released the jibsheet and mainsheet, scrambling forward to lower the mainsail and shouting down to the cabin for sail ties. A few frantic moments ensued as I hung onto the boom, the boat rocking viciously in the seas, while fighting the flapping main down.

I looked back to see Carey gripping the edges of the companionway, fear in her eyes. The struggle left me a bit short of breath, but the main was finally lashed to the boom. Now for the jib. With the boat spinning out of control, I had to judge when to leap to the halyard cleated on the mast, as the clew and sheets thrashed violently against the mast. With cold spray whipping across the foredeck, I crawled forward on the heaving deck to haul the sail down, jamming it into the pulpit and using the sheets to tie it down. Thoroughly soaked, I crawled back into the cockpit to find a white-faced Carey hanging on tight. I gave her a reassuring smile, which was far from what I felt. We were in trouble.

Glancing around, I took stock of our situation. The boat was still afloat, with no water inside, and aside from being very uncomfortable in the rolling seas, we were not in immediate peril. But the rudder was useless, and there was no way to repair it with the tools we had on board. The relative safety of sheltered water was at least 2 miles behind us to wind- ward. But by now, the current in the pass would have turned against us. Did we have enough boat speed to beat the flowing water if we got back there? I had no thought of continuing across the open water — we had to get back to the calmer waters in the lee of the islands. Without another boat in sight to provide assistance, it was up to us to get there.

Using a butter knife, I straightened the cotter pin holding the rudder onto the stern and dragged the fractured rudder onto the cockpit floor. It wasn’t going to do me any good flopping about on the surface. Lowering our trusty outboard into the water, I began pulling, and it started on the second try. Leaning over the stern, I was able to pivot the motor and regain some directional control. Against the rising wind and building seas, we started powering back toward Porlier Pass at an agonizingly slow speed. The clouds that had been near the horizon were now almost upon us and the sun was hidden behind the ominous darkness.

Bert works to repair his broken rudder on the dock at friendly Telegraph Harbour Marina.

Carey and Nicky stayed below, and I slid the hatch closed to keep the spray out. Every once in a while I’d see Carey’s head pop up, checking to see if I was still there and all right. I would give her a smile, letting her know everything was under control. And it was. Uncomfortable, but under control. What seemed like hours passed as I leaned over the stern with one arm on the outboard. The salt spray was icy and the air temperature dropped rapidly as the cold front rolled over us. I was so pumped with adrenaline that I didn’t notice the cold, but my arm and body were starting to shake. Hypothermia was becoming a concern.

As the waves finally subsided on the approach to Porlier Pass, I could relax a bit. Feeling a little more confident, Carey came back on deck. Nicky stayed below, standing in the companionway for safety. Playing the back eddies near shore, I throttled up to maximum speed to slowly inch our way against the now-adverse current in the pass. Years of dinghy sailing in the currents of the Fraser River paid off in identifying where the back eddies were likely to be. But where to go now? We would need to get the rudder repaired before we could head home, but we both had jobs to get back to and Nicky had school. Worst-case scenario, we would leave the boat somewhere and take a ferry home. We agreed to head back to Telegraph Harbour Marina, the nearest facility where we could potentially get assistance with the rudder.

The threatening skies were now fully upon us, rain spitting down with a promise of more to come, the wind still rising. We motored back into the marina and tied up at the spot we had left not long ago just as torrential rain started sheeting down horizontally, the surrounding flags and burgees snapping in the gusting wind. Soaked to the skin, I crawled into the tiny cabin and closed the hatch. We were safe! Time to get into something dry and warm up some hot chocolate.

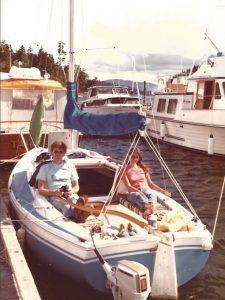

The author and his wife, Carey, relax in the cockpit after the storm, with the repaired rudder ready to go again.

The rain didn’t last long, and within an hour the skies were sunny again, the winds a whisper. We opened the hatches and put our wet clothing on deck to dry. Boaters on the docks, surprised to see us back, listened to our tale in horror. A crowd gathered. The gale-force front had been forecast, but without a VHF or even an AM/ FM radio, we had not heard the warnings. Fellow boaters were oblivious to our plans to cross the Strait of Georgia and certainly would have warned us had they known.

Word of the broken rudder quickly spread. Boaters came from along the docks with saws, drills, and a large variety of nuts and bolts. The marina operators donated the plywood we needed to build splints on both sides of the rudder. I discovered that the fiberglass skin on one side had fractured just below the lower pintle and the foam core had broken, with only the fiberglass skin on the opposite side holding the top and bottom together. I was astonished that the thin skin held it together at all.

Before long, we had bolted on the plywood and reconnected the top and bottom halves of the rudder. After mounting the repaired assembly back onto the stern, we had a working sailboat again. Since the gale warnings had been extended through the day, we prudently elected to stay another night. Fortunately, we always left a buffer day at the end of any sailing adventure to ensure we would not miss a day of work or school.

We found a close-knit boating community on the docks with a wealth of experience and knowledge that everyone was willing to share. We made new friends, toured boats, and shared drinks on a most interesting afternoon. Carey was fascinated with the powerboats. Not that she needed it, but I reminded her of our budget and that the cost of operating such boats was out of the question. Still, she could dream.

The Balboa 20 on her trailer, ready for new adventures.

The following morning dawned clear and bright, with a forecast of light winds. One of our new boating friends offered to escort us back across the Salish Sea to our marina, an offer we couldn’t refuse. As luck would have it, the return across the open expanse of water was anticlimactic. We motored over a glassy sea with not a breath of wind, the jury-rigged rudder holding up just fine.

At home. I fabricated a replacement rudder out of marine grade plywood enclosed in fiberglass. It was identical to the factory model and probably twice as strong. Our family continued sailing that little boat for the rest of that summer. We were hooked on the sailing life. Though still not an avid sailor, Carey loved the social aspect of sailing and would tolerate the sailing part. We moved up to an O’Day 25 the following year, and then eventually to our first Islander Bahama 30.

Although we are far more experienced now and much more comfortable on a 30-foot boat, that first year on the Balboa 20, with its sense of exploration, still holds a special place in our memories. We learned to be prepared and self-sufficient, and discovered that in a crisis on the water, everyone is willing to help. We have returned the assistance many times over the years.

As sailors, we all have to start somewhere. And Telegraph Harbour Marina, a reflection of that remarkable afternoon, is still one of our favorite marina destinations today.

Bert Vermeer and his wife, Carey, live in a sailor’s paradise. They have been sailing the coast of British Columbia for more than 40 years. Natasha, an Islander Bahama 30, is their fourth boat (following a Balboa 20, an O’Day 25, and another Islander Bahama 30). Bert tends to rebuild his boats from the keel up. Now, as a retired police officer, he also maintains and repairs boats for several nonresident owners.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com