… and two more mid-’80s designs

Issue 148: Jan/Feb 2023

The 1987 Hunter 33.5 predated my arrival as chief designer at Hunter in 1992, but was still in production until 1994. It was then replaced under my tenure by the 336 in 1995. I suspect that the 33.5 was actually designed by my predecessor at Hunter, Ola Wettergren, although as was common practice with Hunter, in-house designers were seldom credited. Cort Steck preceded Ola in that role. One reason for Hunter not touting their designers, of course, was not only the often-rapid turnover of design staff , but also the influence that Waren Luhrs, and through Warren, Lars Bergstrom, had on the design process. The designer was often listed as “Warren Luhrs and the Hunter Design Team.” It was Warren’s company, so he had every right to do that, and it also added continuity in the development and promotion of new product, not linking new designs to any individual designer.

The 1987 Hunter 33.5 predated my arrival as chief designer at Hunter in 1992, but was still in production until 1994. It was then replaced under my tenure by the 336 in 1995. I suspect that the 33.5 was actually designed by my predecessor at Hunter, Ola Wettergren, although as was common practice with Hunter, in-house designers were seldom credited. Cort Steck preceded Ola in that role. One reason for Hunter not touting their designers, of course, was not only the often-rapid turnover of design staff , but also the influence that Waren Luhrs, and through Warren, Lars Bergstrom, had on the design process. The designer was often listed as “Warren Luhrs and the Hunter Design Team.” It was Warren’s company, so he had every right to do that, and it also added continuity in the development and promotion of new product, not linking new designs to any individual designer.

The boats chosen to compare to the 33.5 are the 1984 C&C 33 Mk2, which was an all-new design, bearing no semblance to the original 1974 model of the 33, and the 1985 Beneteau First 325, built at the Beneteau plant in North Carolina. The C&C 33-2 was introduced at the end of my tenure at C&C, immediately prior to my joining Mark Ellis Design in 1985. I have little memory of working on the design, as I was busy with other projects. I do have some knowledge of the boat, however, after having put down a deposit to buy a used C&C 33-2 a few years ago. Although it can’t be seen in the sail plans and the figures, the C&C certainly reflects the often-undesirable impact of the IOR, with her extremely flat bottom and elimination of any semblance of a fillet between keel and hull, whose joint is as close to a right angle as you can get. Upon examining the boat out of the water, we saw extensive repaired grounding damage to the hull in the vicinity of the keel. We rapidly backed away.

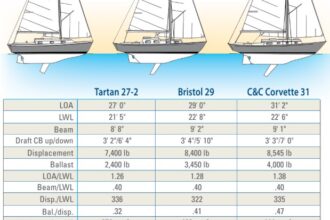

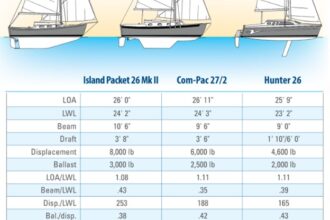

These boats represent the homogenization of production boatbuilding and design in the mid-’80s, all having fin keels and spade rudders, and incorporating the influence of the IOR rule on yacht aesthetics and design, notably in their wide beams and moderate overhangs. However, the Hunter departs from that common aesthetic with the incorporation of a fractional rig with a large fully battened mainsail, and a small, barely overlapping easy-to-tack jib. While she sports swept-back spreaders, which would soon become the norm on most boats of this period, Hunter had yet to completely adopt the full B&R rig which would be introduced by Warren Luhrs and Lars Bergstrom during my tenure with the company. The mainsheet arch, too, would soon be introduced. Hunter was also an early adopter of the bulb/ wing keel as a standard confi guration as a means to achieve a lower draft without unduly compromising stability. Note she has 12 inches less draft than the Beneteau, and 18 inches less draft than the C&C! However, to try and further compensate for that reduced draft, her ballast weight and displacement are higher than the C&C and Beneteau, resulting in the highest displ/LWL ratio of a still sprightly 250, compared to 235 for the C&C, and a suspiciously competitive 200 for the Beneteau.

Note also the flattening of shear lines during this period, with the Hunter and Beneteau actually sporting straightline shears, while the C&C still incorporates an attractive but very moderate curvature compared to boats of the 1970s.

The Hunter has the largest sail plan at 520 square feet, with the C&C slightly less at 511, and the Beneteau substantially less at about 440 square feet. These numbers generate SA/displacement ratios of a respectable 17 for the Hunter and 18.3 for the C&C, but a low fi gure of 15.5 for the Beneteau. The latter may refl ect her European heritage.

The wider beams and lighter displacements push the capsize screening numbers precariously close to the threshold figure of 2 for the Hunter and C&C, and slightly above for the Beneteau. Comfort ratios also refl ect the lighter displacements and wider beams.

If you want to use the numbers to predict comparative performance, it would be hard to beat the C&C with the highest SA/displacement ratio, a very competitive displacement/LWL ratio, the highest ballast/displacement ratio, and the deepest draft. Aesthetically, the C&C is certainly attractive, which drew us to her in the first place a few years ago. If only she had had more bottom curvature and a keel fillet, we might be sailing her today, although that 6 foot 4 inch draft would have severely complicated our cruising ability.

These are three fine designs from the mid-’80s. Good

Old Boat Technical Editor Rob Mazza is a mechanical engineer and naval architect. He began his career in the 1960s as a yacht designer with C&C Yachts and Mark Ellis Design in Canada, and later Hunter Marine in the U.S. He also worked in sales and marketing of structural cores and bonding compounds with ATC Chemicals in Ontario and Baltek in New Jersey.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com