… And Two More Water-Ballasted Trailer-Sailers

Issue 142: Jan/Feb 2022

The Hunter 260 is an evolution of the Hunter 26, which was developed during my tenure at Hunter Design. As Allen Penticoff mentions in his review, it incorporates a number of deck modifications introduced after my departure, including a revised transom more suited for wheel steering, relocation of the forward hatch from the middle of the “windscreen” to the foredeck, and the addition of the B&R (Bergstrom and Ridder) rig so beloved by Warren Luhrs. (Warren and Lars Bergstrom were close friends and sailed many miles together aboard Thursday’s Child.) The 260’s sail plan also underwent a few modifications to produce a slightly larger sail area, but the interior layout and details remain essentially unchanged.

In the early ’90s, the sailboat industry was exploring the concept of water ballast as pioneered by Roger MacGregor. The goal was to reduce the all-up weight of a trailered boat so it could be more easily towed by a smaller vehicle and more easily launched and retrieved from a ramp. Why lug around a fixed weight of lead ballast that could amount to 40 percent of the boat’s total weight if you could avoid it?

In the early ’90s, the sailboat industry was exploring the concept of water ballast as pioneered by Roger MacGregor. The goal was to reduce the all-up weight of a trailered boat so it could be more easily towed by a smaller vehicle and more easily launched and retrieved from a ramp. Why lug around a fixed weight of lead ballast that could amount to 40 percent of the boat’s total weight if you could avoid it?

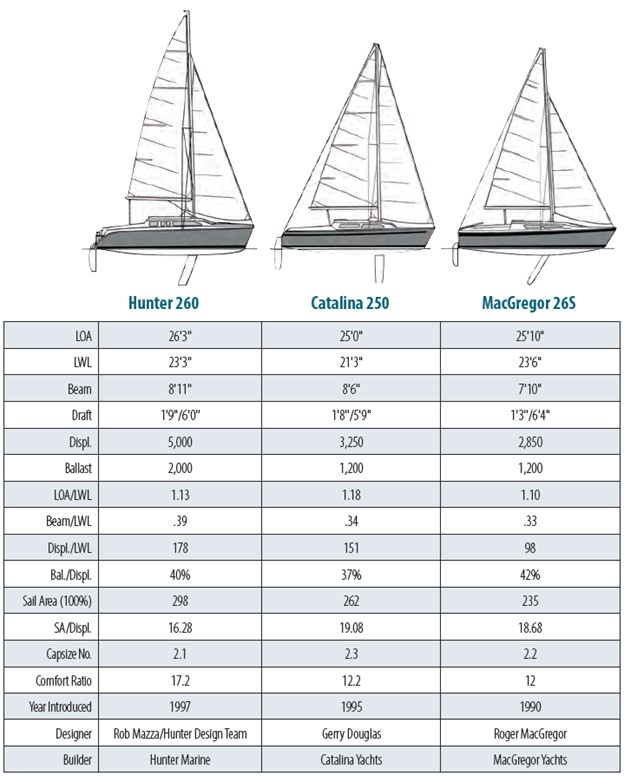

In this period, the three big players were MacGregor with the 26S, Hunter with the 26 and later the 260, and Catalina with the 250. The MacGregor 26S is a centerboard development of the original MacGregor 26D, which had a vertically lifting daggerboard.

In “Water Ballast for Trailer-Sailers” (July/August 2019), I explored the inherent compromise of water as ballast, specifically its volume being 10 times greater than an equivalent weight of lead, and the resulting increase in the height of the boat’s center of gravity. For instance, the 1,200 pounds of ballast in two of our comparison boats would require only 1.7 cubic feet of lead but now requires 19 cubic feet of fresh water. This would raise the ballast center of gravity substantially in a configuration that is already high since the ballast is housed in the hull, not a deep keel.

This highlights an additional water ballast issue for trailered boats. Designers have traditionally incorporated a wider beam to achieve greater form stability to compensate for a high center of gravity. But for highway towing, the allowable maximum beam in most jurisdictions is 8 feet, or in a few cases 8 feet 6 inches, beyond which you need special permits and equipment. Note that only the MacGregor meets the 8-foot restriction, with the Catalina aiming for 8 foot 6 inches, while the Hunter cheats a little with 8 feet 11 inches, perhaps hoping no one would notice, or that the owner would be holding the other end of the tape if stopped by the highway patrol!

So, if stability is the defining characteristic of water-ballasted trailered boats, what can we tell from the numbers? The MacGregor has the lightest displacement at 2,850 pounds and the narrowest beam at 7 feet 11 inches. It does have the same weight of ballast as the Catalina at 1,200 pounds, so its ballast/displacement ratio at 42 percent is slightly higher than the others, but certainly not high enough to make up for that narrower beam when sailing upwind in any sort of breeze.

However, sailing stability is a trade-off between righting moment and heeling moment, and the MacGregor has reduced its heeling moment by incorporating the smallest sail plan at 235 square feet—which still produces a high sail area/displacement ratio of 18.7. It also has the squattest rig, in an attempt to lower the heeling arm. Yet despite these efforts to reduce the heeling moment, we can still safely say that the MacGregor would be the most tender of the trio.

The Hunter 260, on the other hand, would certainly be the most stable of the three. It tops out as the heaviest at 5,000 pounds (400 pounds heavier than the Hunter 26) with the greatest amount of ballast at 2,000 pounds and substantially more beam at 8 feet 11 inches, as well as the lowest sail area/displacement ratio of 16.3, despite having the largest sail area.

Note that the Catalina is the only one of the three to employ a masthead rig, while all incorporate swept-back spreaders and shrouds, and the Hunter eliminates the backstay completely with her B&R rig. Most boats that are on the tender side—which all three have to be considering their high centers of gravity—use fractional rigs so the larger mainsail can be quickly eased or reefed when required.

Like most small boats, each has a capsize number above the threshold of 2, which is more a reflection of their light displacement than their narrow beam. The comfort numbers also follow the displacement numbers.

Each of these boats achieves its stated purpose of more easily and economically broadening an owner’s cruising options by allowing easier towing, launching, and retrieval with a smaller vehicle than would be possible with a traditional ballasted keel/centerboarder. Having personally towed and launched the Hunter 26 and her smaller sister, the 23.5, around Florida, I can certainly attest to the usefulness of that advantage.

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Rob Mazza is a mechanical engineer and naval architect. He began his career in the 1960s as a yacht designer with C&C Yachts and Mark Ellis Design in Canada, and later Hunter Marine in the U.S. He also worked in sales and marketing of structural cores and bonding compounds with ATC Chemicals in Ontario and Baltek in New Jersey.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com