To rest or wait out weather, heaving to remains a tried and true tactic at sea.

Some seafaring traditions are worth carrying on, especially those based on knowledge and techniques derived from thousands of years of misfortunes and triumphs. The art of heaving to is such a tradition.

No matter what body of water we sail on, heaving to helps us tame a sailboat in a ruthless environment. It provides calm when we need it and can let us focus on other tasks. It is the closest we can get to parking a sailboat in the middle of a squall on a lake or a tempest on the ocean. If we have the sea room to do it, that slow, predictable drift can let us pass a few minutes or hours to wait for better conditions, to tuck into a reef, or to simply make a cup of coffee. No technology has yet to match the power of wind and waves, but this proven technique can help keep us safer and make our time on the water more enjoyable.

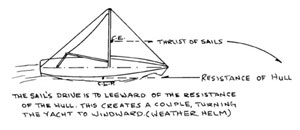

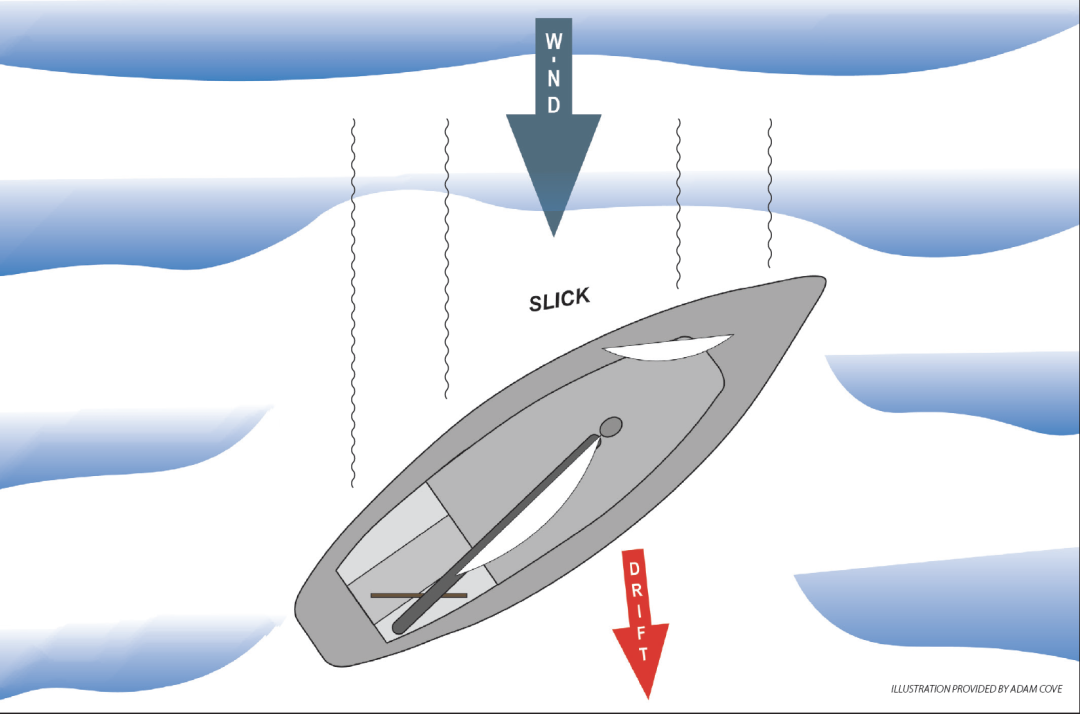

On our 1969 Luders 33, Ben-Varrey, our typical hove to configuration is a back-winded jib or staysail, with the main traveler slightly above center and the tiller lashed to leeward. In this setup, the main- sail and tiller are trying to steer the boat up into the wind, but the jib is driving the bow back down. With these opposing efforts balanced, Ben-Varrey ceases to make any noticeable forward progress as she sits about 55 degrees to the wind. The boat slides downwind, typically between a half-knot to 2 knots, creating a slick to weather that protects the vessel from breaking waves.

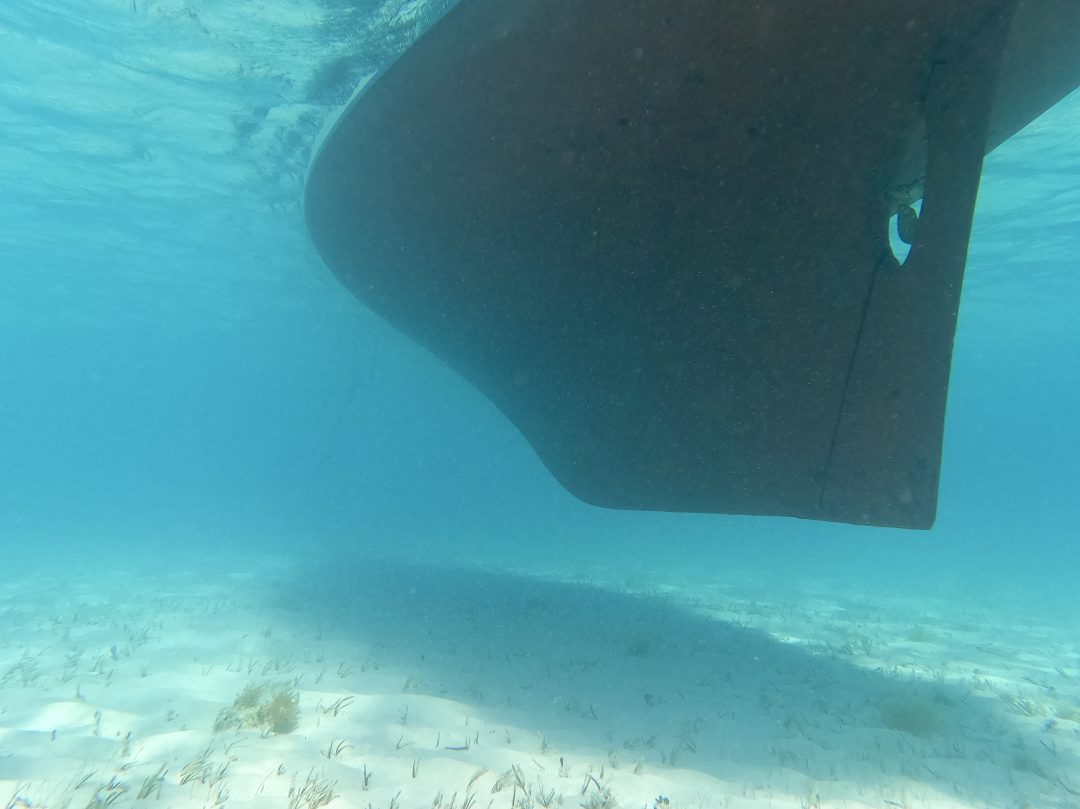

Older boats, especially those with full keels, easily lend themselves to heaving to. The underwater hull form is more forgiving with low aspect ratio foils that are difficult to stall. They provide consistent influence, or grip, on the water around them, enabling a position to be more easily held to the sea. A traditional hull shape also provides more drag when moving sideways through the water, controlling the rate of drift and developing a more influential slick to weather. Furthermore, older hulls feature more wetted surface area. This creates added resistance to moving forward, keeping the vessel hove to instead of forereaching.

These traditional design aspects are the same reason older designs track better but struggle to hit the same top speeds as modern designs. It is a design trade-off, but one that carries a considerable advantage in rough conditions.

Ben‐Varrey’s hull shape is a traditional full keel with an attached rudder, easily lending itself to heaving to.The hull shape is only half of the equation, though. A properly hove to boat also requires equilibrium above deck. The sail plan must be appropriately sized and balanced. Too much canvas will result in excessive heel and undue load on the vessel. As sails are shortened to match the conditions, that process must happen equitably behind and in front of the mast. In a more technical sense, it is maintaining an appropriate longitudinal center of effort. This is affected by every sail flown. When a main is reefed, not only does its center of effort drop to a lower height, but it also moves forward (because sail area is subtracted aft and above). With high roach mainsails, this change becomes more pronounced as the reefs get deeper.

Hove to configuration for Ben‐Varrey. A slightly modified arrangement may be required for other sailboats as a result of alternate sail plans and underwater hull shapes.

To balance out this shift, the center of effort of the headsail must move aft. That is why a staysail on an inner forestay is helpful as weather becomes heavier. That same sail, farther forward on the headstay, would drive the bow of the boat down to leeward. Yawls and ketches have other options, but still need to solve the same problem — maintaining sail plan balance. This is where time should be spent experimenting. Try heaving to on your own boat in a variety of wind strengths and sea states to see how it handles. Learn how to balance the center of effort of the hull shape with that of the sails. Remember, fine-tuning is managed with the rudder position as well as the main sheet and traveler.

Aboard Ben-Varrey, we’ve successfully used this technique to manage heavy weather, delay a landfall, and to calm the boat for rest or cooking. It is a practical skill in any sailor’s seamanship tool kit, and can be especially helpful for those who sail shorthanded. Here are a couple stories to bring you on board our boat when we have opted to heave to.

Galesville, Maryland, to St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands — Singlehanded

While watching weather windows to sail southeast from the East Coast of the U.S., we noted that the first front to roll through carried a steady 60 knots out of the north. Place that against a possible 3-knot current in the Gulf Stream and I was likely to encounter conditions that resembled magnified Class V whitewater rapids because the period of waves is shortened by adverse current. With this much current, the faces of the waves were bound to become so steep that they would break regularly. Rolling the boat in those conditions was not only a possibility, but a strong likelihood. The forecast had only been for 45 knots, and I didn’t trust the northerly direction, so I was glad to have waited in Galesville to avoid a disastrous departure from the Chesapeake Bay, although the tail end of the system did provide a nice push to start down the Chesapeake.

Adam Cove with a reef in early on Ben‐Varrey as incoming weather approaches.

There didn’t appear to be a decent weather window — it was one front after another, followed by a large high pressure system moving in that would suck all the air out of the area for well over 100 miles. So when the next front was accompanied by a southerly wind, it was time to head to sea. I could make enough progress on the next system that would follow, and those would be westerly winds anyway.

I cleared Cape Henry around 4:30 p.m. and still carried the 130% genoa to make my way through the remnant swell in a 10-knot breeze. It was expected to build, and by 6:30 p.m. I had switched to the 90% jib and set up the staysail. The wind was only 13 knots at this point, but it was far easier to make these sail changes when stepping up to the foredeck didn’t mean participating in a rodeo.

The wind reached 20 knots around 2:00 a.m., and by 6:30 a.m. it was pushing 26 knots from the south. I put in a second reef, and then at 6:50 a.m. I lashed down the 90% jib and hoisted the staysail. Thirty minutes later it was a steady 40 knots, with gusts touching 45 knots. Ben-Varrey was sailing too fast and jumping off the backside of the waves, and water was dumping into the cockpit. It was time to slow things down.

I sheeted the staysail to weather, lashed the helm to leeward, sheeted in the main entirely, and adjusted the traveler until all but the smallest amount of forward speed was gone. A slick developed on the water to windward and Ben-Varrey began to drift downwind at a slight angle, the waves unable to touch her, with no more spray and a steady heel of about 15 degrees. The breeze felt like it had been cut in half. A calm breakfast, followed by drying off the cabin sole and taking a nap, filled the morning.

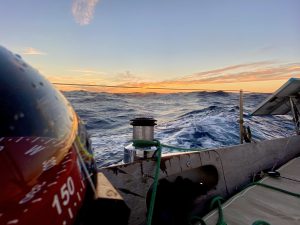

Ben‐Varrey sailing fast in the Atlantic as the weather builds. She hits a top speed of 16 knots over ground minutes before this image is taken.

The winds abated by the afternoon, and Ben-Varrey and I were once again on our way. I gradually added canvas, and then a shift of the breeze to the south- west pushed boat speeds to an 8-knot threshold. Making progress east meant continued breeze by getting ahead of a looming high pressure system. I avoided any damage to Ben-Varrey and felt well rested — both crew and boat were ready for the next 1,200 miles of the passage.

Roque, Maine, to Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts — Doublehanded

My wife, Alison, and I finally lost sight of the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Cobia that had been near us for most of the night as we crossed through the southern Gulf of Maine waters. It appeared they were doing some routine patrols in the rough weather — maybe breaking in some rookies? We were outside the shipping lanes that run north by northwest off the eastern coast of Cape Cod and were even in latitude with the middle of Stellwagen Bank. Aboard Ben-Varrey, we were sailing much faster than expected and closing in on Pollock Rip Channel. It would still be dark when we rounded the first mark, and although we had navigated it only a week earlier, the sands shift quickly around Monomoy Island.

Position plot of Ben‐Varrey as she hove to off the coast of Cape Cod, on her way from Roque Island, Maine, to Vineyard Haven, Massachusetts. Adequate sea room is needed while using this technique to allow for drifting to leeward at slow speed.

A strong current sweeps across the shoals, in excess of 2 knots at peak. A visual fix, to verify the required course correction against the GPS, is tough to achieve in this frequently foggy area. There are two lighthouses (one abandoned) to reference and a series of lit markers, hopefully in position, that were hiding in the 12- to 15-foot seas, and the otherwise dark space of a wildlife refuge. The waves and the shoals also don’t mix well, and we could expect lots of breakers ahead.

The decision to heave to was made before we even got a quarter of the way down our list of reasons. We also knew that the current would switch shortly after dawn, making for a more peaceful transit of these waters and a building push through Nantucket Sound.

We were on a screaming broad reach, already had a single reef in the main, and had shifted down to the 90% jib the afternoon before. Our apparent wind would noticeably increase as we turned into the wind. At the time, we were already feeling a steady 30 knots, and with the forecast calling for the wind to build, we should have already shed more canvas. Before we moved into a hove to position, we put a second reef into the main, set up our storm jib, and proceeded to create a few more miles of sea room. We were already 35 miles offshore, having cheated another 10 miles offshore earlier when we thought this might be a possibility. With an onshore breeze, sea room gave us flexibility and safety.

Ben‐Varrey underway in the North Atlantic. After heaving to, a warm glow from the sunset breathes in comfort as the waves subside.At this point, neither of us had been able to get much sleep. When we finally tacked the boat over and hove to, it was bliss. We took turns napping and popped our heads out of the hatch every so often to check for anyone else crazy enough to be out there with us. Only a couple of fishing boats were in the area, as far as we could tell, and they never came closer than 7 miles. The breeze built to 40 knots, with gusts into the upper 40s. We saw a few waves in the high teens, but most stayed around 15 feet.

Dolphins swim along beside Ben‐Varrey, guiding her to Pollock Rip Channel where she can safely navigate through to Nantucket Sound.

As dawn came, the wind remained, and we stayed hove to for a few more hours. Once the breeze dropped into the low 30s, we peeled off and began making progress to the southwest. A pod of dolphins swam with us for 20 miles while we surfed our way to Nantucket Sound. Well rested and under control, we passed though Pollock Rip Channel and began to add sail as we pushed for some well-deserved ice cream in Vineyard Haven.

If you have sea room and are in need of rest, or want to comfortably cook a meal or wait out some weather, heaving to is an ideal tactic. It calms the situation and provides a gentler motion for the boat and her crew. I have often forgotten the true conditions when I have been below deck while hove to. It is a form of magic that we can only thank previous generations of seafarers for passing along. If you haven’t already, try it out on your next sail, and add it to your seaman- ship tool box for future passages.