“The shock of discovering bubbles on your boat’s bottom is merely the prelude to a prolonged pain in the assets.”

Boat pox, osmosis, or blisters . . . call it what you will. Most fiberglass boatowners prefix the blight with a salty expletive deleted. The shock of discovering bubbles on your boat’s bottom is merely the prelude to a prolonged pain in the assets.

Parnassus, my beamy Montego 25 sloop, was built by Universal Marine in St. Petersburg, Fla., in 1980. That was just about the time I had sworn off boat ownership in favor of crewing aboard OP (other people’s) craft. But last year I lapsed. My reaction to a 40th school reunion in a room filled with geezers jockeying for parking space for their walkers propelled me to recapture the spirit of adventure I vaguely recalled from my youth . . . that of owning a boat.

The sticker price of Parnassus removed most of the lumps from under my mattress. And the discovery of a badly blistered bottom has siphoned off the balance.

Twenty years ago the annual haulout to scrape, sand, and bottom paint an earlier boat was a week-long project. My land-lubberly lifestyle during the interim had not exposed me to the blister blight, which apparently hit its zenith a decade ago when fiberglass, the panacea for all boat hull maintenance woes, mutinied.

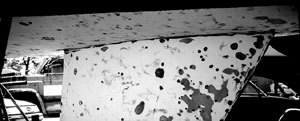

Today, many boat owners – including me, now – are aware of the cancerous reaction of water collecting under the hull gelcoat to create an odoriferous vinegary bubble of acid formed when moisture – from the ocean outside, or bilge water inside – reacts to solvents, resin, or additives in porous pockets beneath the gel surface. Those voids, perhaps no bigger than a pinhead, may have been created by just one speck of dust in the builder’s boatyard – so you can imagine the possibilities. Or perhaps it was the failure of boatbuilders to totally resin-soak every last fiber of chopped strand mat between the gelcoat and woven-roving laminated layers. That inner skin of chopped matting supposedly prevents the woven roving pattern from emerging on the surface of the gelcoat, making the hull look like a floating waffle . . . whereas the surface of a blistered bottom – once the pustules have been pricked – resemble the pocked face of the moon.

Unfortunately, the aesthetics of what, primarily, would be the boat’s profile under the waterline, is a minimal problem compared to the dire predictions of fiberglass layers de-laminating, structural failure, a cracked seeping hull, and death by drowning.

All this and much more, I learned from leather-skinned liveaboards and margarita mariners lined up at the boatlift as Parnassus was hauled out last June. After that, the boatyard manager, Jason Sprague, told me my carefully estimated haulout and bottom job bill would have to be revised upward . . . somewhere near the stratosphere.

A professional labor/cost guesstimate, quoted in one of the many magazines, newspapers, and books about blisters I devoured researching the repair process, projected a $350-plus-per-foot price tag. That included peeling the bottom to the first layer of woven roving, re-glassing, fairing, and barrier coating, then repainting the bottom with anti-fouling bottom paint.

A professional labor/cost guesstimate, quoted in one of the many magazines, newspapers, and books about blisters I devoured researching the repair process, projected a $350-plus-per-foot price tag. That included peeling the bottom to the first layer of woven roving, re-glassing, fairing, and barrier coating, then repainting the bottom with anti-fouling bottom paint.

Forking out the best part of $10,000 to float my boat, was not an option. Fortunately, Old Slip Marine, Riviera Beach, Fla., is a “do-it-yourself” yard. UN-fortunately, despite abbreviated classes at the Eastbourne Technical School, England – 40 years ago – my handyman skills would make Rosie the Riveter blanch. But, faced with a boatyard hourglass dumping dollars by the day just for storage, I was shocked into becoming a semi-shipwright.

Jason explained the yard’s procedure for curing the ills, after waltzing around Parnassus with a moisture meter which pegged off the scale (25 percent) from the keel to the rubrail. The moisture meter indicates how much potential liquid is trapped under the gelcoat, poised to provide more blisters.

The blisters needed to be popped then ground off down to the roving. Ideally, Jason said, the hull should be professionally peeled to the roving. Then the boat should sit and dry out until water drained out or evaporated, and the moisture meter lowered to about five percent. To encourage that, the hull should be pressure washed with a hot-water machine.

The blisters needed to be popped then ground off down to the roving. Ideally, Jason said, the hull should be professionally peeled to the roving. Then the boat should sit and dry out until water drained out or evaporated, and the moisture meter lowered to about five percent. To encourage that, the hull should be pressure washed with a hot-water machine.

Estimated time: two to three months! Florida in the summer is not the most pleasant place in which to don full protective dust-suit, mask, head sock, and filter-respirator. All this prior to entering a still-air cavern created by the environmentally-correct tarpaulin-shrouded hull of Parnassus in which to begin grinding. During the summer of 1998, while Florida went up in flames, boatyard temperatures and humidity readings competed to break the 100-degree barrier. It was a tad nastier under the tarps, where the grinder created intrusive toxic dust clouds of multi-layered old bottom-paint, gelcoat, and fiberglass.

There were more than 100 blisters, from pinhead to half-dollar size, for the grinder to eviscerate. I circled a dozen locations with a waterproof felt-tipped marker and marked them with date and moisture meter readings. Twice during the next two months, her hull was pressure washed with hot water to encourage the trapped water and acid to seek the surface.

After two months, no new blisters appeared, but there was barely any downward movement in the moisture meter readings. According to some experts, the hull must be totally dry before repairs can begin. On the other hand, there are those who have little faith in moisture meter results and prefer to patch and plop dinged hulls – wood or fiberglass – after an eyeball, feel, and balance determination.

After two months, no new blisters appeared, but there was barely any downward movement in the moisture meter readings. According to some experts, the hull must be totally dry before repairs can begin. On the other hand, there are those who have little faith in moisture meter results and prefer to patch and plop dinged hulls – wood or fiberglass – after an eyeball, feel, and balance determination.

The balance part of the equation is weighing whether the Band-Aid approach or boatyard advice method will leave a positive-dollar balance in the old bank account. Like all things connected with boats, it’s a compromise.

We opted to work within the guidelines offered by the boatyard boss, plus snippets garnered from old salts in their slips, marine hardware store employees – most working to keep their own boats afloat – and published pundits, from boating journalists to marine surveyors.

The following list of procedures worked for Parnassus and, today, knock-on-wood, she’s blister-free and floating.

Parnassus is my getaway floating island, whether she’s tied up at the slip, moored in the lake, or day-cruising when wind, tide, and time allow. There are no plans for any solo long-distance bluewater voyages, ala Joshua Slocum or Robin Lee Graham, in her future. She was designed to perform under MORC (Midget Ocean Racing Club) rules and as a comfortable family cruiser. There may be moisture in her hull adding to her weight and slowing her down, but whether she’s cruising downhill with a following wind at seven knots or less, we’ll be out on the water . . . sailing.

And a pox on all blisters!

The Process

Hauling At the time boat is hauled and pressure washed, the blisters will be most apparent. Mark them before they drain or deflate. Wear protective goggles when popping and scraping them. The liquid is often under pressure, and a squirt in the eye can be harmful.

Grinding A grinding wheel should be used to smooth the cavity created by exposing the blister pocket and to fair it down at the edges to allow epoxy filler to meld with the contour of the hull. Sanding with coarse-grit paper does not do the job efficiently.

Drying out The blisters are visual indications that pockets of acid exist under the gelcoat. But there may be more latent moisture seeping from water tanks or bilges within the boat, trickling through or trapped between layers of fiberglass, moving toward the gelcoat. A two- to three-month drying out period is a prudent step to take.

Wash down To encourage chemical liquids within the hull to leach to the surface and to speed up the drying-out process, hot water washdowns are recommended.

Patching The most widely touted method for patching blister damage, because of its ease of application, is the West System brand of epoxy products. However, the yard manager at Old Slip Marine claimed fewer customer complaints and a higher success rate when his experts used the Interlux two-part InterProtect Watertite compound. One can contains the base materials, a cream-colored putty-like gook, the other a blue paste containing the curing agent catalyst which binds both elements into a steel-hard set-up finish. The mix is two-parts cream to one-part blue.

Cowboy, the resident yard helper for the past decade, demonstrated the proven consistency, eyeballing amounts, texture, and color until the combination turned aquamarine. He advised only mixing sufficient material for about 20 minutes of work – depending on the temperature of the day. The approved boatyard palette is an ordinary piece of packing-box cardboard. A wooden tongue-depressor is used for mixing.

Sanding Once the fill has set up, sand the entire hull (80 grit) to level out patched blister cavities and rough the surface in preparation for the barrier and bottom coats. Tip: least used is easiest removed. Because we were too liberal in applying the mixture with a putty knife, when it set up solid as steel on the hull surface, it added hours to the time needed to sand the fill down fair.

Scrubbing Scrub the hull down, using a stiff-bristle brush and hot soapy water to rid the surface of dust and any dormant chemical residual. Interlux recommends using their fiberglass solvent wash 202. However, when we tried it, our workgloves dissolved, the linen-rag disintegrated, and our hands looked like bleached prunes. Barrier coat We skipped the next step: applying a barrier coat of Interprotect 2000E/2001E which re-seals the hull and replaces the gelcoat. Although we had more than 100 blisters to repair, more than 80-percent of the original hull finish (gelcoat) remained intact and unblemished. If, as the experts say, blistering is formed where voids exist under the gelcoat because the water is trapped under the skin, we reckoned the integrity of her hull – after almost 20 years – would survive a little longer.

Bottom paint We opted for Fiberglass Bottomkote ACT antifouling paint, based on the local knowledge of the boatyard manager. Old Slip Marine has been a family-operated business for more than three decades and is familiar with the barnacle build-up potential of a variety of gunkholes, marinas, and slips in the area. The reputed advantage of ACT as a soft paint permits the surface to wash away by water movement over the hull constantly exposing fresh and effective biocide. It also eliminated bottom paint buildup and, I hope, will require less sanding to prepare the hull at the next haulout. We shall see.

Article from Good Old Boat magazine September/October 1999.