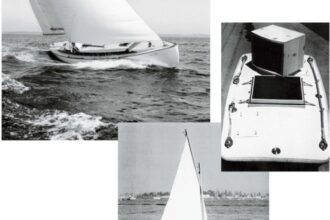

Helping a classic Alberg come to life as a racer-cruiser

Issue 149: March/April 2023

Sailing — moving a craft through the water using the wind’s energy — is a magical experience. Witness the variety of explanations put forward over the years as to how those curves of fabric above us move our boats in the directions we choose. From a dead calm with the boat motionless in the water, a light air appears and the boat starts to move ever so slowly. As the wind builds, our vessel’s speed increases, it begins to heel, we attain the highest speed that the craft’s design allows, and then we start to reef. We transition from trying to capture all the energy we can from the wind to shedding the energy in excess of what can be used to move the boat.

Sailing — moving a craft through the water using the wind’s energy — is a magical experience. Witness the variety of explanations put forward over the years as to how those curves of fabric above us move our boats in the directions we choose. From a dead calm with the boat motionless in the water, a light air appears and the boat starts to move ever so slowly. As the wind builds, our vessel’s speed increases, it begins to heel, we attain the highest speed that the craft’s design allows, and then we start to reef. We transition from trying to capture all the energy we can from the wind to shedding the energy in excess of what can be used to move the boat.

Working against our sails is the resistance of water. That resistance is made up of two elements: friction between the water and the hull and wave-making. Both slow us down, stealing a portion of the energy that our sails have managed to capture. Wave-making is mainly beyond our control; the shape of the hull and the nature of water dictate the waves that the boat will make for any given speed. We can shift our position on the boat to maintain proper heel and pitch, but that’s about it. Skin friction, however, is where we can take action and substantially improve our lot. The easiest step to take is to clean the hull, to remove all the plants and animals that come to live with us below the waterline. A foul bottom can make a boat with a 23-foot waterline, sailing at 4 knots, a quarter-knot slower than she would be with a clean bottom.

Once the bottom is clean, the next step is to make the bottom both fair and smooth. A bottom that curves gradually throughout from the entry to the stern, without obstructions protruding into the fl ow of the water, is fair. Sanding a fair bottom to remove surface texture, all those little ridges, bumps, and hollows that you can feel when running your fi ngertips lightly over the hull, makes the bottom smooth. Clean, fair, smooth bottoms move through the water with a minimum of resistance. Those boats are fast.

Here’s how I created a fair, smooth bottom on Constance, a 1967 Alberg 30 that I transformed over several years from a decidedly cruise-only boat, restoring her original purpose as a competent racer-cruiser.

Sanding Time

Just before I purchased Constance in May 2015, the previous owner applied an ablative paint to her bottom. I hauled her in the winters following both the 2016 and 2019 sailing seasons to address various items. Each time, I sanded the bottom, roughening up the existing paint to allow the two coats of new ablative paint to adhere well. Constance started racing in 2019 when the skipper of the Alberg 30 I had raced with for 20 years decided it was time to take a break. The experience was more than a bit humbling. Bad starts. Slow at the starting line. Stretched-out sails. Undersize genoa and spinnaker. Excessive rake. Excessive weather helm. There was a lot to fix. Speaking with the other skippers and practicing helped to address some of the problems. Purchasing a full-size spinnaker in early spring 2019, reducing rake while replacing the standing rigging in 2020, and purchasing a new genoa and a nearly new mainsail in 2021 addressed a number of problems. Constance had become competitive but not a podium boat. Now that she had the sails to capture the wind, the single major improvement remaining was to stop wasting the energy captured above the waterline on resistance below the waterline.

At the end of the 2021 sailing season in Annapolis, Maryland, Constance was hauled out for the winter’s work, with temperatures quite often being in the 40s. On the last day of November 2021, I started work. Wearing a Tyvek hoodie/ footie suit, T-shirt, jeans, and full face 3M 7800 respirator provided enough insulation from the cold while sanding the bottom that I was comfortable, neither chilled nor sweating. It took six hours of sanding with a 5-inch random orbital sander and 60 grit Diablo 5-inch SandNet discs to make a first pass over the bottom, the equivalent of what I had done in both 2016 and 2019.

This first pass of sanding revealed blue bottom paint, perhaps six coats, below the three layers of red ablative bottom paint that had been applied since 2015. Below the blue paint was a layer of resin. It appears that at some point, a previous owner had removed all the paint, mixed resin and hardener, and coated the bottom. After this initial sanding, the resin and the blue paint appeared in patches. Each of these patches was a spot where the hull surface stood a bit proud of the area around it, assuming that I had sanded the bottom evenly.

Having gotten a sense of the task before me, I spent the rest of December on other jobs. It was not until mid-January that I resumed work on the hull. Fifty hours of sanding later, nearly all the red bottom paint was gone and reasonably sized patches of resin were visible. Two to three hours with a sander vibrating in my hands and a Shop-Vac buzzing away collecting the sanding dust was fatiguing, and quite enough for one day, despite the full face mask and high-quality 30dB NRR ear muffs. One more pass over the hull and another 10 hours of sanding removed the remaining blue paint, exposing the layer of resin everywhere.

Constance came to me with a good through-hull depth sounder, but the transducer was mounted on a teak “fairing block” that stuck out of the hull about an inch and a half … not good. The next task was to remove the transducer and the fairing block, then to grind back and fill the hole. For this job, an angle grinder worked well.

With all the paint gone, it was time to find out just how fair the hull might be. A 24-inch longboard sanding block, dry guide coat kit, and 60 grit sandpaper revealed the amount of variation in the surface of the hull. An alternative to dry guide coat is a carpenter’s pencil. Scribble liberally over the area to be faired and then longboard until all the pencil marks are removed. I was quite happy to find that the resin layer had a bit of thickness to it, perhaps an 1/8-inch, so that I could use the longboard to sand away some portion of that 1/8-inch of resin to the extent required to even out the hull. Had Constance been lacking this coating, I might have ended up longboarding through the factory finish into the fiberglass of the hull at the high spots to bring them down even with their surrounding areas.

Longboarding away a portion of the resin coating dealt with the high spots. For the lows that remained, I turned to applying filler. The filler I ordered, TotalFair, came with a plastic spreader, which is what I used. Bad move. Despite pressing hard while spreading the filler to the low spots and leaving a minimal amount of filler on the surrounding areas, the lows ended up overfilled. The plastic spreader deformed enough to create a bulge away from the hull in the middle of the spreader. Longboarding these unneeded and unwanted high spots of filler was time-consuming and frustrating. It was the one part of the project that created unnecessary work. In retrospect, I should have used a metal putty knife or putty spatula to spread the filler.

Running a 24-inch longboard over the hull is a bit of work. Very fine sanding dust flies off the board throughout the first hour; maintaining the same rate of progress through the second hour was tough. Into the third hour of longboarding figure-eights over the hull, I was toast. Two hours of longboarding seemed to be about what I could do well in a day. The color of the Tyvek suit at the end of each longboarding session confirmed the progress being made. Slowly the color turned from reddish, to purplish, to bluish, until finally becoming very fine white shavings rather than dust. By that point, I had removed all the paint from the bottom of the hull and evened out the surface.

Crafting a New Bottom

After 25 hours of longboarding the hull, the time had come, finally, to begin creating the new bottom. Having chosen the bottom paint based upon recommendations from skippers in the Alberg 30 racing fleet, I applied the compatible primer, Pettit Protect Heavy Duty Two Component Epoxy Primer. Two layers, white over gray, would give me four mils of white primer to longboard before cutting into the gray primer below. The ¼-inch nap roller I used resulted in significantly less texture in the dried surface of the primer than on other boats in the yard painted with ¹¶4-inch rollers. Less texture meant less time spent longboarding the primer and less primer lost to sanding.

Given the texture in the primer from the ¼-inch nap roller, I spent about seven hours wet-sanding the primer using a longboard. Over the course of longboarding, March turned to April, then mid-April. Time was getting short. The season was fast approaching, and other projects needed attention as well.

Finally, the day came to apply bottom paint. After applying two coats of hard paint, Pettit Trinidad Pro, it was time to complete the job by burnishing the paint, wet-sanding using the 24-inch longboard and 320 grit sandpaper. The hull was now fair and smooth enough that I had to be careful when starting the longboard moving to make sure that the sandpaper stayed adhered to the longboard rather than to the hull. It had gotten to the point that the water used in wet-sanding could bond the sandpaper more tightly to the hull than to the adhesive holding the smooth side of the sandpaper to the longboard. It took only a couple hours to longboard the entire bottom with 320 grit.

Race Ready

Constance launched the next day. A few weeks later, the sailing season began in earnest as the Annapolis Yacht Club started its Wednesday Night Series, which runs from late April through September. That race series provided the crew of Constance with three practice races before the 2022 Helly Hansen Sailing World Regatta in Annapolis. Each day of the regatta we improved upon the previous day’s results. The first day was spent sorting ourselves out, but the second day resulted in a third- and second-place finish. The final day only had one race due to there being no wind at all, followed by rather light air. Light air was just what we needed because it meant slower speeds and less energy lost to wave-making, leaving skin friction as the dominant force of resistance to be overcome. These conditions would demonstrate the fairness and smoothness of the bottom relative to the rest of the fleet. Sail trim would be critical. We had to capture as much energy as the winds would allow.

close to the windward mark.

A kerfuffle at the start resulted in both Constance and the previously undefeated Alberg 30 being forced over the line early. The two of us dropped back from the fleet to below the starting line, restarted, and chased the fleet. With 5 knots of true wind, Constance was hitting the speeds indicated by the ORC’s velocity prediction program. The crew worked together remarkably well, allowing both the genoa trimmer and the skipper to focus on their primary jobs of watching telltales and trimming to match. The other crew members quietly relayed positions of the boats in our fleet and the GPS speed over ground readings. After an hour of intense racing, two legs to windward and two downwind, the finish was so close neither boat was sure who won until we asked the race committee. Constance finished just ahead of the Alberg that had won every other race in the regatta!

much speed downwind as possible.

This winter, 2022-2023, Constance is staying in the water while I work on some of the creature comforts aboard. My current thoughts are to haul out the winter of 2023-2024, longboard away much of the existing bottom paint, further fair the hull, taper the trailing edge of the rudder, apply two more coats of hard bottom paint, and then longboard with 320 grit again. Hopefully, the result will be a fairer and smoother bottom than this year’s. Gaining a tenth of a knot increase on an average of 4.5 knots of boat speed would result in a lead of nearly four boat lengths per nautical mile. To obtain that advantage takes many hours of bottom preparation. To me, though, a fair bottom is worth the effort.

Changing jobs from downtown Washington, D.C., to Annapolis, Maryland, led Jonathan Bresler to begin racing a variety of keelboats in the summer of 1998. With retirement approaching in several years, he purchased Constance in the summer of 2015 and began racing her in 2019. The bottom job of 2021-22 was the last structural systems refit. Next up are the comfort systems to prepare her for racing/cruising the Chesapeake Bay and beyond.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com