For a new sailor, a fateful trip sparked a seemingly impossible goal.

Issue 148: Jan/Feb 2023

When the sailing bug bites, it bites hard. It got me while spending 21 days aboard Selkie, a custom aluminum boat captained by its female owner, exploring the Orkney Islands of Northern Scotland. As we cruised these sparsely populated islands, rich with Viking history, I was amazed at what I saw— from finding myself climbing down into the Neolithic tomb on the Holm of Papay to walking in the fields of North Ronaldsay, watching its famous sheep graze. We sailed into the ancient seaport village of Stromness in pea soup fog, transited the Caledonian Canal, passed castles on the shores of Loch Ness. My life was forever changed.

That was in the fall of 2014, and when I stepped off the boat and onto the dock, I was determined to make sailing my life. Upon returning to Los Angeles, I set out to get onto as many boats as I possibly could, from crewing on several boats for races in Southern California to volunteering as crew on long-distance yacht deliveries. I slowly built up experience sailing under different captains on a variety of boats.

By April of 2017, I found myself standing on a splintered wooden dock in a marina that is regularly called “the place where boats go to die,” staring in amazement at my dreamboat—a 1965 Alberg 30, hull number 55, that I had just purchased. She hadn’t left the dock in more than six years, her engine was seized, she possessed no equipment other than the original mainsail and a few mismatched headsails, her rigging looked to be from the ’70s, and she had a beard of old growth on her undersides that could have been declared a protected marine site.

Still, I knew I had just pulled off a miracle finding an early Alberg 30 with no soft spots on deck, no water damage in the cabin, and plenty of potential. She had not been butchered down below, and it appeared that for most of her life she had either been loved or at least not sailed very hard. The weather in Southern California surely helped, with not much rain and fairly mild temperatures near the water.

I had been obsessively shopping for boats for a few months before finding her and had mostly been looking for Tritons, Cape Dorys, and even some Tartans. My main requirements were a bluewater boat with a full or long keel that was made before 1972 and cost less than $12,000, which was all the money I had. I never expected to find a 30-foot bluewater boat within my budget, so when I stumbled on an Alberg 30 for $2,500 I drove—no, SPED— down to the Los Angeles harbor, passing Mad Max-esque refineries and pump jacks along the way. The moment I saw her, I knew she was perfect. That was the day I met Triteia.

My intentions were simple and seemingly impossible— refit the boat and untie the lines to sail around the world by spring 2020. If these seem like lofty goals, let me up the ante a bit. When I bought Triteia in 2017, I knew I had to address her mast step deck beam that was in danger of delaminating and her undersized chainplate bolts, both of which are known weaknesses of Alberg 30s, as well as numerous major projects to transform her into a bluewater cruising boat. But first I needed to get her running and sailing again, with the goal of spending the Christmas holidays under anchor at Santa Cruz Island in California’s Channel Islands.

The following months found me with no shortage of old boat grime covering my arms and busted knuckles on both hands as I worked feverishly getting her back into sailing condition. Some of the major projects included replacing the half-rusted and seized Yanmar 2GM20 that sat in the engine bay with a beautifully rebuilt Yanmar 2GM20F I had found for sale online. I also pulled out the questionable batteries and removed all of the wiring from the boat, most of which looked like lamp cord wire from the 1970s, and rewired the boat with all marine grade wire. Not wanting to cut any corners, I stayed up late at night obsessively reading Nigel Calder’s Boatowner’s Mechanical and Electrical Manual.

Within three months of Triteia being a shell in a sad marina, I was leaving Angels Gate Lighthouse to starboard on her first sail. A few weeks later, I sailed her to Catalina Island for the first time for a long weekend tied up to a mooring at the isthmus. She was still a rough-looking girl, but I was beaming with excitement! My dreams were coming true before my very eyes.

After that first adventure and realizing that my goals were within reach, I managed to pull off the seemingly impossible task of working a full-time job and getting Triteia equipped for my dream trip to the Channel Islands for Christmas. I would get off work at 5 p.m. and drive 30 minutes to the boat, work until midnight, drive 45 minutes home, and repeat the process. I built out a custom anchor locker and installed a chain pipe. I purchased a 35-pound Delta knock-off anchor and attached it to 80 feet of ³³8-inch BBB chain and an absurd amount of ¹³2-inch rope rode. I also picked up a manual Lofrans windlass (whose wildcat, I discovered, did not fit my chain) and installed a bow roller for the anchor. Other important projects before the big adventure included installing an anchor light and steaming light and rewiring the running lights. I also bought and wired up an autotiller, installed a holding tank for the head, and added a few creature comforts in the form of a cabin light and a USB charging port.

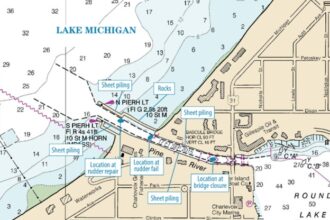

By the grace of Neptune, I managed to pull it all off in time for my holiday trip. I had two weeks off work for the holidays and I was finally going to head out into the wild and isolated Northern Channel Islands, which include Anacapa, Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel. Other than park rangers and campers, the islands are all uninhabited. There are no mooring fields and no facilities for provisions or parts. The Channel Islands are known for high winds due to their neighbor to the north, Point Conception, which regularly sees gales tear past as they head south, hitting the windward side of the islands. To spend time cruising in these islands, you must be completely self-sufficient and be able to trust your ground tackle and your abilities.

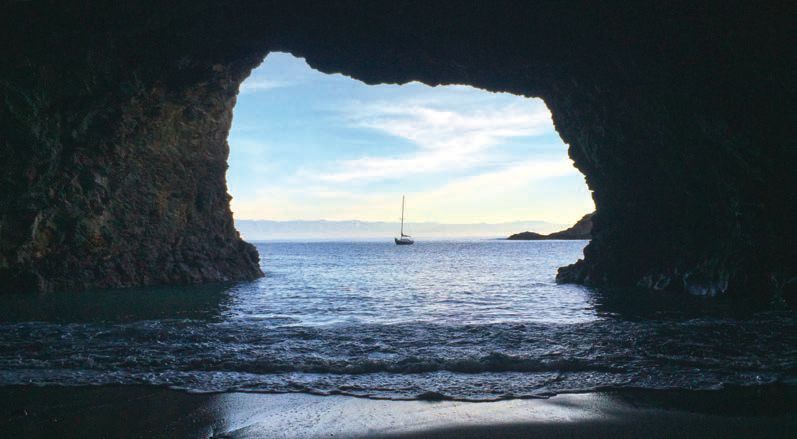

I provisioned, fueled up, and did battle with my overzealous packing gland, which was pouring water into the bilge at a steady stream instead of the one drip a minute common with this type of gland, and soon I was motoring into the twilight through the Los Angeles harbor. After a 23-hour overnight passage of some 90 nautical miles, I sat in the cockpit of my dream boat watching an incredible sunset under anchor at Coches Prietos anchorage on Santa Cruz Island. I spent the week between Christmas and New Year’s circumnavigating the island, staying at a new anchorage each night. It was, up to that point, the greatest week of my life. The trip was full of learning experiences and stresses, but I found myself smiling constantly even in anchorages so rolly that I was forced to sleep on the cabin sole so I could wedge myself into place and not tumble about all night long.

Over the next four years, I completely refit the boat slowly and in phases of intense work for months at a time, followed by exploring the islands and anchorages of Southern California. Some of the notable projects I tackled included replacing all bronze fittings below the waterline with Groco tri-flange seacocks, replacing the packing gland with a PSS dripless shaft seal, having a custom stern tube made, building an integral 35-gallon water tank in the bilge, installing a compression post beneath the mast, and enclosing the head with a hot water shower and “wet head” floor.

I also replaced the mast and all rigging with a custom rebuilt mast and masthead, converted to a double spreader rig, and built a custom hard dodger. Many of the projects were documented on my YouTube Channel as how-to videos, while others are yet to be chronicled. This is nowhere near a complete list of upgrades, but I might suffer from PTSD if I were to publish a full list of all the projects. To maintain my sanity, I consider boat projects and maintenance as an “adventure tax.”

Triteia good in a seaway.

As for my impossible dream? I made a solo crossing to the Hawaiian Islands in August of 2021, only one year delayed from my original plan after the world shut down due to the global pandemic. During the 2,300 nautical-mile passage, a few other boat projects revealed themselves—most notably, a total steering loss 1,000 miles from Hawaii that stretched the passage out to 32 days. After wintering in Hawaii and repairing my rudder, I sailed south to French Polynesia, making landfall in the Tuamotus before going on to explore the Society Islands, American Samoa, Fiji, and on to New Zealand, where I am spending cyclone season.

We all know boat work is never really done, and oftentimes it feels like a labor of love—or a labor of misery. But when all is said and done and we untie the lines and push off the dock for a day of quietly sailing along or burying the rails with the helm in hand, it’s worth it.

James Frederick is currently circumnavigating aboard his 1965 Alberg 30 sloop, SV Triteia. After years of adventure sailing in Southern California, he untied the lines for good and pushed off to see the world. You can follow along with his adventures at youtube. com/sailorjames.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com