A dreamy cruise is interrupted when the head calls it quits.

Issue 142: Jan/Feb 2022

A number of years ago, my family and I sailed Dreamer, the first of two Islander Bahama 30s we’ve owned, from the Vancouver area of British Columbia north to Desolation Sound. The passage was as we’d hoped—sunny days with enough wind to fill the sails—and once there, we enjoyed peaceful overnight anchorages.

Life aboard was wonderful except for one, nagging issue: With the dawning of each new day, the manual marine toilet got harder and harder to pump.

I had replaced the original toilet, hoses, and holding tank when we purchased Dreamer a few years before. I thought the toilet pump O rings were probably getting a little stiff, so I poured a bit of vegetable oil into the head and pumped it through, hoping it would lubricate them. No dice.

As was typical of boats in British Columbia waters at the time, Dreamer’s toilet had the ability to pump directly overboard or into a holding tank. Perhaps, I thought, the problem was at the Y- valve. The good news was that the toilet still worked, albeit reluctantly, and the sailing itself was idyllic.

Then early one sunny morning, the pump handle simply refused to go down, even when I applied considerable pressure to it. As a bucket wasn’t high on the options list for my wife and daughter, I decided to head for the nearest point of civilization. There was no point in taking the toilet apart, I thought, without having access to parts. We tied to the public dock at the little village of Lund, British Columbia, which is an interesting place to visit, but more importantly had a marine supply store nearby.

The girls went ashore to avoid the language they knew would be coming. The temperature outside was well into the 80s, without a whisper of a breeze. The first thing I did was try both Y-valve positions to see if the pressure at the toilet pump handle changed. It did not.

This meant that the blockage had to be somewhere in the hose between the toilet and the Y-valve. I assumed that the hose was under pressure, as well, which did not bode well. (Aboard a friend’s boat in which a small vent hose had somehow gotten plugged, the holding tank system became so pressurized that a 1 ½-inch hose under the V-berth ruptured in the wee hours of the night! The story was side-splittingly funny when told over drinks, but I’m sure it wasn’t at the time.) There was nothing for me to do, however, but loosen the hose at the toilet and hope for the best.

I didn’t get sprayed, but it was not a pleasant job, especially in the heat. The standard 1½-inch sanitation discharge hose was about 5 feet long with an upward sweep from the toilet through a bulkhead, then down to the Y-valve in a small locker. Sweating mightily, I endured a lot of twisting, pulling, and bruising of knuckles to get the hose off the barbs, then through the tight-fitting hole in the bulkhead.

Out on the dock, an examination revealed that calcium deposits (scale) had reduced the diameter of the inside of the 1 ½-inch hose to no bigger than the tip of my pinky finger. I was amazed that anything had managed to get through at all. Fortunately, the nearby chandlery had a replacement hose. It was a simple matter of snaking the new hose into position and clamping it in place, and our head was once again a smooth operator.

(If no hose had been available, I would have slapped the hose on the dock to knock the calcium out, which I have since learned is a tried-and-true technique for clearing these hoses, not to mention it does wonders for one’s aggravation level when dealing with this unpleasant problem in the first place.)

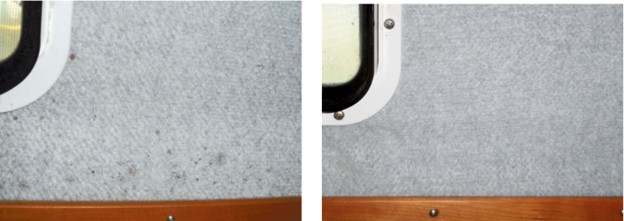

The lesson learned? Just because the hose is shiny and white on the outside doesn’t mean it’s the same on the inside. It needs to be inspected. Now that particular section of hose gets replaced every three years, usually with about ¼-inch of calcium buildup on the inside. I have replaced the rest of the waste plumbing with hard PVC pipe, which doesn’t seem to collect calcium at the same rate.

The girls are happy, which means I am happy. The memory of that day rises to the surface every time we approach the dock at Lund, at which time I usually tip a cold one in the direction of the head.

Bert Vermeer and his wife, Carey, live in a sailor’s paradise. They have been sailing the coast of British Columbia for more than 30 years. Natasha is their fourth boat (following a Balboa 20, an O’Day 25, and another Islander Bahama 30). Bert tends to rebuild his boats from the keel up. Now, as a retired police officer, he also maintains and repairs boats for several non-resident owners.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com