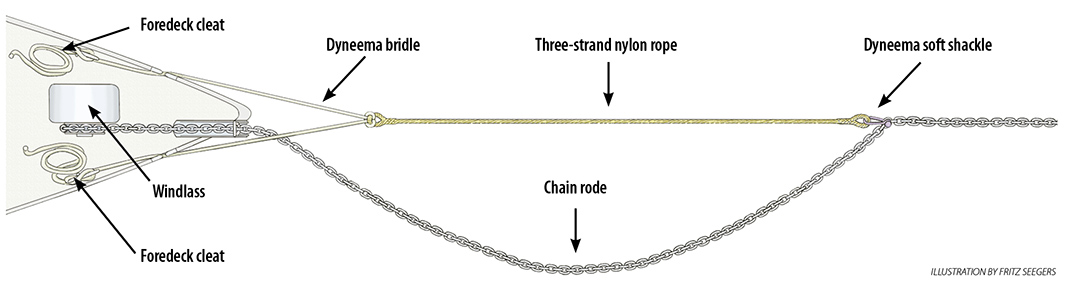

Gino’s snubber in use. A Dyneema bridle, cleated to either side of the bow, attaches to the three-strand snubber shown here as it descends beneath the water.

When using all-chain rode while anchoring, a proper snubber is a critical link.

Issue 138: May/June 2021

Carolyn and I cut the docklines two years ago and we’ve since learned that our ability to securely anchor our boat is arguably our most important boathandling skill. This idea was reinforced last fall as we were moving down the East Coast headed for the Bahamas. While anchored off Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey, a nor’easter blew in with gusts topping 50 knots.

In the middle of the day, a solid bluewater cruising boat anchored just off the beach broke loose. The owner was aboard and recognized the problem immediately, but despite his best efforts, his boat was on the beach in minutes. Fortunately, it was a soft grounding and there was little damage to the boat. Unfortunately, he washed ashore at the peak of an exceptionally high tide and he could not find anyone to get him off for a reasonable price. Ultimately, he had no choice but to sell his boat to a tug operator and fly home to Germany, his dreams of sailing the world dashed.

We’re surprised how often we see boats drag, even when winds are under 30 knots. Most boats seem to have decent ground tackle, but the majority we see anchored have inadequate snubber arrangements, in our opinion. And a good snubber arrangement is critical when using an all-chain rode.

In the Bahamas recently, we saw boats with snubbers that were a jumbled mess, snubbers that were too short, snubbers secured with line-weakening knots, and snubbers with undersized line. Worst of all, we saw boats with no snubber at all. It seems that many sailors don’t really understand the purpose of a snubber. And when it comes to keeping a boat off the rocks, for a boat using all-chain rode, a good snubber is just as important as a good anchor.

When using all-chain rode, a good snubber serves three functions: 1) It isolates a windlass from the rode load; 2) It acts as a sound dampener. Taut chain readily transmits the sounds generated when the chain drags across the bottom; a snubber interrupts that transmission by allowing the chain closest to the bow to go slack; 3) It serves as a shock absorber between the boat and the anchor, isolating the anchor from pitching and surging forces the boat might experience and helping prevent it from being yanked out of the bottom.

Most of the time, conditions in an anchorage are benign and any old snubber fulfills these first two tasks. This lulls sailors into thinking their snubber suffices. It’s only when all hell breaks loose that a snubber needs to work as a shock absorber, and that’s when many fail, to their owner’s dismay. It doesn’t have to be this way.

There are two main considerations for snubbers: the rope used and how that rope is attached to the anchor rode. The rope must be strong enough, long enough, and made of a material with enough elasticity to absorb the shock of wind and wave. For snubber rope, it’s generally agreed that nylon is best; it has good strength, UV protection, and elasticity. The breaking strength of the nylon rope must be equal to or greater than that of the anchor rode.

Look up the breaking strength of your chain rode and then choose a diameter of nylon rope that exceeds that breaking strength. For instance, we use 5/16-inch, high-test chain, which has a breaking strength of 11,600 pounds. Our snubber is made from 3/4-inch, three-strand nylon rope, which has a breaking strength of 17,150 pounds.

Gino’s complete snubber fits neatly into its own bag and has plenty of nylon three-strand for stretch and Dyneema double-braid for chafe protection.

Of course, the snubber must be rigged so that enough line is in use to provide the necessary elasticity, to satisfy the need for shock absorption—and this is where sailors often go wrong. We regularly see boats anchored using snubbers that are way too short, often only 2 or 3 feet. Consider that 3/4-inch nylon three-strand stretches 12 percent at 20 percent of its breaking strength. If we rigged our snubber at 3 feet long, we could expect only about 8 inches of stretch when we need it most. How much good is 8 inches going to do?

Ideally, 3 or 4 feet of stretch should be available to absorb the bow swing-off in a big gust, or the pitching or surging that results from a big swell or wave entering an anchorage. Unfortunately, in our case, this amount of stretch would require a snubber that is approximately 44 feet. We’ve used snubbers up to half the length of our boat, but in shallow Bahamian anchorages, for example, we find that the far end of the snubber is often sitting in sand or mud (the dirt and grit can damage the line over time). We’ve compromised with a snubber of 15 feet, which gives us acceptable—if not ideal—shock absorption.

There are a variety of ways to attach the snubber to your chain: you can tie the snubber to the chain using a rolling hitch or similar knot; you can use a commercial chain hook; or you can use a solution like we employ, a soft shackle of 1/4-inch Dyneema. The rolling hitch can work if it’s tied properly, but as with any knot in a rope, it becomes a weak point. Commercial chain hooks can work, but they’re susceptible to falling off when the chain rode goes slack (although some newer designs eliminate this drawback—but they are expensive).

Gino fabricated a Dyneema soft shackle to attach the snubber to the chain. It’s stronger than the three-strand nylon it’s attached to, doesn’t fall off, and doesn’t seem to wear.

Our favorite approach, the Dyneema soft shackle, has the advantages of being secure and easy to rig. The 1/4-inch Dyneema has a breaking strength of 9,700 pounds, which is 1,900 pounds less than the chain, but anything thicker and I can’t get it through the chain links. This introduces a known weakest point, but I reason that this weakest point is still strong enough (and the chain hooks I’ve seen don’t even publish their breaking strengths). To use the soft shackle, it’s simply a matter of joining the eye spliced in one end of the 3/4-inch nylon snubber to a link in the chain rode.

To attach our length of snubber to the boat, I use a bridle made from a 20-foot length of 12-mm Dyneema sheathed in a length of New England Ropes Endure Braid, for sun and chafe protection. I use a cow hitch at the center of the 20-foot Dyneema to attach it to the eye in the boat end of the snubber, then run the resulting two 10-foot legs of the bridle through chocks at the bow and cleat them off.

Once I’ve got the snubber attached, I let out enough chain so that the snubber has accepted all of the load, and then let out roughly 6 more feet of chain so that the snubber can stretch several feet without the chain coming taut.

All in all, our system allows us to get a sound sleep in even the windiest and bumpiest of anchorages. Now all we worry about is the other boats anchored upwind of us with poorly constructed snubbers—hopefully they read Good Old Boat.

Gino and Carolyn Del Guercio have lived aboard their Brewer 44, Andiamo, for the past few years, spending summers in New England and winters in the Bahamas. Andiamo is one of very few boats that have twice graced the cover of Good Old Boat.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com