Nearly 90 years old, the revolutionary Northill anchor continues to inform today’s generation of ground tackle.

Issue 138: May/June 2021

At first glance, it’s just another fisherman anchor. But a closer examination of the Northill anchor reveals an impetus and geometry that revolutionized anchor design. The Northill laid the foundation for an entire class of new-generation anchors, including the Mantus, Manson Supreme, Rocna, and Spade.

Before the Northill, anchors were largely designed to hold vessels primarily through dead weight and limited digging. But in the early 1900s, flying boats became the future of transoceanic transport, and carrying an anchor with the dead weight required to hold a high-windage aircraft in place while it was in the water was incompatible with getting airborne. A far more efficient approach was needed.

By considering how planes move through the air and how tools cut metal, John Northrop (yup, the airplane guy) and his nephew, architect Harry Gesner (who trained under Frank Lloyd Wright), set out to design an anchor that would “develop holding power largely independent of the weight of the anchor.” The two men put a completely new spin on the traditional fisherman anchor by enlarging the flukes, changing angles, and moving the cross stock to the crown, where it could improve holding capacity and roll stability.

They made their anchor foldable and fabricated it from stainless steel (non-magnetic). They applied for their patent in 1933 (US2075827), and the Northill was soon the standard-equipment anchor on the Consolidated PBY Catalina (known as the Canso when flown by the Royal Canadian Air Force).

About this time, Richard Danforth came up with his own lightweight anchor design that was also widely adopted for military use, primarily to pull grounded landing craft off the beach, but also to anchor flying boats. Because Danforth’s anchor used the same basic angles, Northill Manufacturing sued him in 1942 for patent infringement. The court decided the designs were too different to be considered conflicting and let it go.

After World War II, Northill Manufacturing advertised its product as the first “scientifically designed” anchor and started selling it to the recreational marine market. A simpler version, the Northill Utility, was also introduced. Made of galvanized steel, it features a simpler folding mechanism and great durability.

Both continued in production through about 1954, when the patent expired. Northill knockoffs, including the KB Ultralight, were produced as recently as the mid-1970s. These days, commercial fishermen are about the only users of the Northill design (homemade welded knockoffs adorn the bows of commercial fishing boats around the world), but the protruding fluke is a liability for overnight anchoring; the rode can wrap around the fluke, potentially tripping the anchor.

Playing the Angles

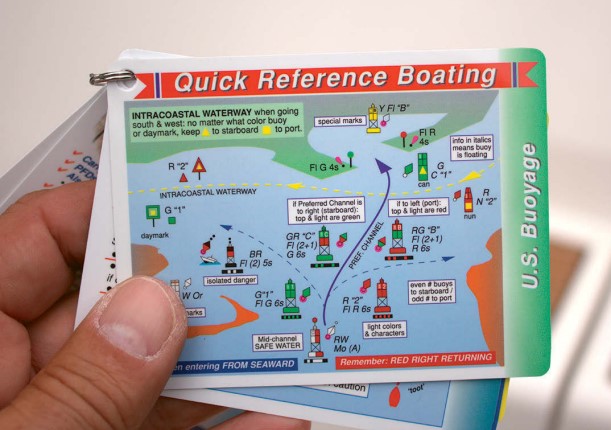

How an anchor digs and holds is largely dependent on the fluke-shank angle, and all new-generation anchors have an angle that falls within a very narrow range. Too great, and the anchor won’t dig into harder bottoms. Too shallow, and the anchor will shave its way into the hardest bottom, but it won’t go very deep and holding power will be limited.

In fact, all modern anchors have a fluke-shank angle that is within a few degrees of the Northill design, the perfect compromise between initial bite and maximum holding power in sand and firm mud bottoms. Notably, the Fortress anchor (a descendant of the Danforth) has an adjustable angle (32 degrees or 45 degrees), with a default setting of 32 degrees. If set at 45 degrees, the Fortress won’t penetrate sand or firm mud, but it becomes monstrously strong in soft mud and will dig many feet below the surface, into firm mud underneath. Thus, fluke angle is a compromise, and the most generally useful geometry was introduced by Northill.

Still Working

I’ve used the same 12-pound Northill Utility anchor aboard three different boats over a span of nearly 30 years. Occasionally, the Northill was the primary anchor, often it was a secondary or special use anchor, but it always saw regular use.

Before the invention of tip weighting (Delta and Spade) and roll bars (Bügel and its descendants, including Mantus, Rocna, and Manson Supreme), a cross stock was used to force the tip into the bottom. It works marvelously, angling the fluke toward the bottom so that it is ready to dig. Like all modern anchors, the tip is sharp, and it is capped with a beak to help penetrate weed and sneak into the cracks.

Setting is extremely rapid, within a shank’s length in firm bottoms. When the crown of the anchor reaches the bottom, the cross stock channel digs in securely, reinforcing the hold. Although the cross stock will continue to bury under increasing load, this generally stops with the upper fluke still barely exposed. Unless extreme force is used, the shank is generally only slightly buried and the cross stock just slightly under the surface.

Although the fluke area on a Northill is smaller than that of a new-generation anchor of equal weight, holding capacity is very similar; the forward portion of the fluke, located in deeper, firmer, stronger soil, provides most of the holding capacity, and the Northill fluke is in a forward, deep position. The cross stock also provides considerable grip. Tested against modern roll bar anchors in sand and mud, the holding capacity per pound is 70-100 percent, depending on the bottom and the competing anchor.

Because the Northill fluke is relatively small and sharp, it sets easily with limited power, such as with a small outboard. A larger fluke would increase holding capacity but would make setting and penetration of weeds and hard bottoms more difficult—a compromise. As long as the current does not reverse, the cross stock makes the Northill very stable, able to rotate to face the new wind direction without disengaging from the bottom.

I bought my Northill for anchoring over shale, cobbles, and oyster rock, an application where fisherman anchors were known to shine. My 25-pound Delta would often just slide along on its side, but the 12-pound Northill would hook right in, often out-performing anchors as much as three times heavier. Aboard boats from 1,200 to 9,000 pounds, when I am fishing over rock slabs and oyster rock, the Northill is my go-to hooking anchor.

I discovered another benefit of the Northill when I began sailing my F-24 trimaran. The foredeck anchor locker on that boat is too shallow to accommodate any of the new-generation anchors, and while a Danforth or Fortress would fit, they don’t suit all bottoms or deal well with wind shifts. My Northill Utility anchor folds flat in seconds by releasing a clip and withdrawing the cross stock, and it fits easily.

The Catch

I have found a couple of downsides to the Northill. First, unless it will be folded for storage, it is awkwardly large. On the other hand, it is not as ungainly to handle on deck as you might suppose and will rest comfortably on the crown, supported by the flukes and cross stock.

Worse, if the wind or tide does a 360-degree rotation, and the transition is not gradual, the rode will likely wrap around the fluke. This scenario has unfolded for me a few times, without causing the anchor to drag, but only because I was very lucky, and the wind was light. Otherwise, once fouled, the anchor will pull out as easily as if you pulled on a tripping line. This fatal flaw generally relegates the Northill to fishing, lunch-hook, and second-anchor status.

Many have suggested that the folding design could be fragile, but that’s not been my experience and I’ve not found user reports of fragility. (I’ve seen photos of bent shanks, but the accompanying stories describe anchors that were caught between rocks and aggressively horsed on during recovery.) As for durability, I’ve never seen a rusty one, and that’s pretty impressive for a galvanized anchor that’s 80 years old. They did something very right.

I have one of practically every anchor on my shelf: Danforth, Delta, Excel, Fortress, Manson, and Mantus. Mushrooms, claws, and grapples. And yet, this 90-year-old design still holds a place on my A roster for difficult bottoms.

Does a Northill make sense in your anchor lineup? If your anchoring is always sand or mud, modern designs are more convenient to handle, hold slightly more, perform slightly better in wind shifts, and most importantly, won’t foul during tide reversals. If you anchor in rock or weed, consider a Northill.

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Drew Frye draws on his training as a chemical engineer and pastimes of climbing and sailing to solve boat problems. He cruises Chesapeake Bay and the mid-Atlantic coast in his Corsair F-24 trimaran, Fast and Furry-ous, using its shoal draft to venture into less-explored waters. He is most recently author of Rigging Modern Anchors (2018, Seaworthy Publications).

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com