Pendragon sails up the Patapsco River toward Baltimore.

A short solo voyage comes with challenges faced and lessons learned.

When I was 12, my parents bought me a Sunfish, a little board boat with a lateen sail. I’d been reading about sailing for years and my green-cover copy of Royce’s Sailing Illustrated was dog-eared. One spring day, with nothing more than what I’d gleaned and some vague directions, I rigged the boat and pushed off, alone. I didn’t get far, but I learned a bit and for the rest of the summer, it was just the boat and me, dancing with the wind and water. I loved that feeling and I didn’t know it then, but I had become a sailor.

As an adult, I owned a few small cruising boats and came to learn about navigating and exploring new waters and places. Those boats taught me a lot, but I never thought to take them out alone, I always had company. No complaints, but I missed the solitary thrill I remembered from sailing solo as a boy.

When I bought my fourth boat, an Alberg 35 I called Pendragon, I could barely find the courage to take it out of the slip in Baltimore where I moored. It seemed huge and wasn’t as nimble as the smaller boats I’d owned. Also, I’d recently married a non-sailor, and while she was steadily taking to the boat, I frequently found myself standing on the dock on a beautiful, breezy day. My boat was willing and able, but I was frustrated and stuck.

I found myself thinking about sailing alone again. I read the classic singlehanders: Slocum, Moitessier, and others. I began to imagine a single-handed cruise aboard Pendragon. Then I began practicing, slowly.

By my third summer with the boat, I was gaining some confidence handling her alone. I knew that the long keel meant tacks didn’t snap, they were ponderous. I knew better than to try and stop her — even when she moved at a crawl — by holding on to the dock with a boathook.

After I’d tried a few day sails in the company of crew who did their best to not help me in any way, I planned a 20-mile solo adventure cruise to the Magothy River. I decided on a first-day stop in Rock Creek, near the mouth of the Patapsco River (Baltimore’s home river), since I’d anchored there before.

When the day came, I made a float plan, provisioned the boat, set up charts, and off I went, springing out of the slip. I was tense, scared, and as excited as I’d been the first time I pushed out on my Sunfish.

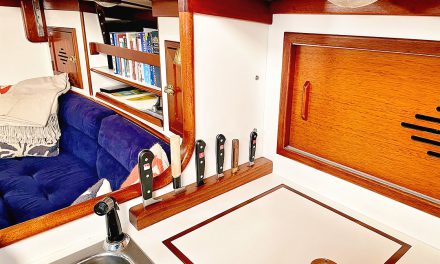

Jim takes time out for some coffee on the cabintop.

I’d imagined a sailing trip, but the Chesapeake wasn’t cooperating. I set the autopilot and motored along, hoping the wind would appear. When I got thirsty and realized water and other things I needed were in the cabin, I left the helm nervously, scrambled down the companionway, grabbed what I needed, and got back out again, anxious about the ships and tugs that are constantly coming and going in this busy commercial river.

Halfway to Rock Creek, the wind had freshened — time to go sailing! Raising the main became a bit of an operation. It stuck halfway up, and it took me a while to get things straightened out. Focused on the sail, I lost track of my surroundings. A police launch came by and the officer asked if I was okay, pointing out that I was close to a shoal. I thanked him, moved the boat back into deep water, got the sail up, and unfurled the jib.

The breeze lasted about an hour. It was a nice hour, but it was just an hour. I let the boat ghost along as the breeze died. I nibbled on some prepackaged chicken salad and crackers. I wished for coffee, but I didn’t feel secure enough to go below and start the stove. Finally, I furled the jib, started the engine, took in the main, and motored to the anchorage at Rock Creek.

I’d only ever anchored as part of a two-person team. Despite knowing this anchorage, the depth, and the bottom, I was a bit concerned. Leaving the engine running, with the boat stopped in calm water, I went forward, eased the anchor down, let out some chain, returned to the cockpit, reversed a bit, shifted back to neutral, and ran back to the bow to let more chain out. I did this a couple of times and found the 30-foot trip from the cockpit to the bow getting longer and longer. Then it was time to back down. The anchor grabbed and held, fortunate, as I was tired. I shut off the engine, wrote down cross bearings, and set an anchor alarm on my phone.

Now what? I wasn’t prepared for being alone. I was too tired to cook dinner, so I snacked on chips and things that didn’t require preparation. Instead of feeling like I’d accomplished something, I felt drained. I turned in early, began wondering about the anchor, checked it a few times, and finally fell asleep.

I woke the next morning before dawn, still tired. I sat in the cockpit unsure what to do, not even sure why I was there. None of the books I’d read covered how I felt. I had focused on how to do things, and I realized now that I didn’t know how to just be. So, I did things: I made breakfast, I rowed over to a nearby marina, and I walked.

Returning to the boat, I nearly fell into the water getting out of the dinghy and quickly realized I needed to be more careful. What is simple with someone along is dangerous alone. More than loneliness, what pressed on me was the enormity of total responsibility. There had always existed the possibility of falling overboard or just falling and getting injured, but when sailing with others, there was always someone else to take over. On the Sunfish, I’d been too young to appreciate the dangers. Now they loomed.

As I prepared for the day’s sail, I recalled the previous day and moved water, food, binoculars, and the paper chart to the cockpit, easily within reach. I came to understand that singlehanding is all about foreseeing challenges and preparing for them. The more I prepared, the better I felt. I could do it, I had done it, and if sailing alone was hard, it was a special experience because I owned it. There was no one else but that was the point: It was just the boat and me, the wind and the water. Excitement took hold.

I walked to the bow and retrieved the anchor. It was difficult to rinse the anchor rode and pay attention to the boat’s drift at the same time. It felt like every time I was on top of things, a new challenge appeared.

Finally, I wended my way out the channel, past the shoal to starboard, past the white rocks that give Rock Creek its name, and onto the Bay where no wind greeted me and my boat. I turned on the autopilot and sat back to keep an eye on things, for big boats, for small boats, and for the bobbing floats marking crab pots. The autopilot kept the boat on course, I fussed over small things. I quickly grew bored. And tired. And hungry.

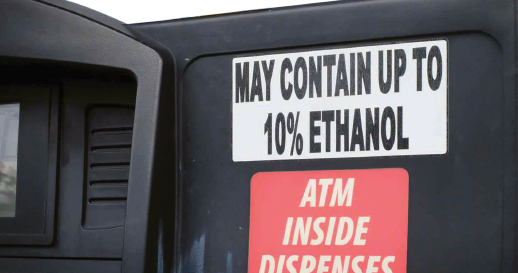

After I passed the marker for Bodkin Shoal, the last creek off the Patapsco River on the south shore, I began a gentle turn south. Then, I began to worry about whether I had enough fuel. I hadn’t anticipated so much motoring in my planning. Searching on my phone, fuel-stop information was sparse; it wasn’t clear there was diesel available on the Magothy River. I fretted and motored, wishing for wind, but late in the afternoon, I gave up and turned around.

That was difficult. I was focused on my destination as a goal, and turning around felt like failure. I was hot, hungry, tired, there had been very little sailing on the trip, and now I wasn’t even going to get where I was going.

Jim tucked Pendragon into Bodkin Creek for the night, though that wasn’t the planned destination.

When I arrived at Bodkin Creek to anchor for the night, I was still a bit dispirited, but anchoring went more smoothly this time and soon the boat was secure and quiet. I watched the birds while trying endlessly to calculate if we were getting any closer to a nearby dock. Details that shouldn’t matter kept grabbing my attention for minutes at a time. Had I been sailing with crew, there would have been conversation to distract me; instead, I spent half an hour getting the anchor light hung just right.

As it got dark, I sat in the cockpit, unmotivated to cook. I had lots of food onboard, but after two days of doing everything, the effort to fill the kettle, light the stove, and fuss over food felt overwhelming. That was my general feeling as a singlehander: over-whelmed. As it got dark, I turned in for the night.

The next morning I pulled up the anchor at 7:00 a.m. and motored the 12 miles home in flat calm. My first singlehanded cruise was over, and it hadn’t been the success I’d hoped. As I thought about it, I realized that much of my exhaustion was simply hunger. I’d not eaten enough to feed the engine of me. I’d forgotten the old cruising practice of making coffee early and keeping it in a thermos to have at hand during the day.

My planning was a problem. I had a goal in mind, and when I didn’t get there, I felt depressed and failed to appreciate how pretty it was where I’d wound up, in Bodkin Creek. My failure to plan for fuel stops or carry a local cruising guide with that information was an oversight, a lesson learned.

On my final day, I was back in my slip by mid-morning, ironically after making the best solo docking ever. As often happens on the Chesapeake, a lovely breeze grew in the afternoon. If I had slept in or simply allowed myself to sit and read, I could have sailed home instead of motoring. On my next trip, I’ll take my time.

And there will be a next trip; I’ll make another singlehanded cruise this year. It won’t be the first time, and that will be a good thing. I know that I’ll never cross an ocean alone, but I’m confident I will reclaim the feeling I experienced in the Sunfish so many years ago.