Issue 134: Sept/Oct 2020

If you’re lucky in this life, you uncover, understand, and embrace what makes you happy. And if you’re gifted in this passion, if you can make it the foundation of your purpose and career, and your desire and aptitude for sharing your passion are equal, then chances are you will give a gift to the world.

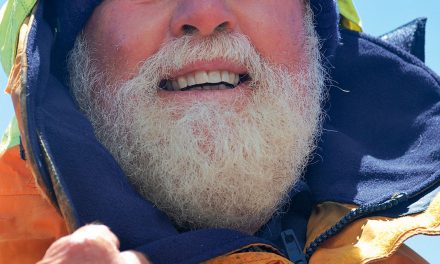

In our world of sailboats and sailing, Brion Toss gave such a gift to many through his craft, skill, and joy as a master rigger. On June 6, Brion died at home at age 69 of bile-duct cancer, and the sailing community lost a singular, luminous craftsman and, by all accounts, a kind and radiant man.

A little over a year ago, I sent Brion an email asking if he’d write an article for Good Old Boat—not about knots or sailboat rigging, but about the life of a rigger, the trade, how someone goes about becoming a rigger. I didn’t know Brion personally, but I’d referenced his books over the years. Who better for this than a rigger-writer?

Brion replied quickly, “Sounds like great fun.” He added that he’d need a couple of months, that he was in “a bit of a medical interlude.”

A couple weeks later, I leaned on my new friend for some advice on an article we were about to run on spreader angles. Brion got back to me with clear, comprehensive information. Months later, when I was about to touch base about the article he was eager to write for us, I heard from another friend that Brion was not well. It sounded dire.

Raw from the then-recent death of Jeremy McGeary, Good Old Boat’s senior editor, I felt compelled to say goodbye, to offer something kind and sincere. I told Brion that I am an amateur student of information design, “and I think your Rigger’s Apprentice book is a master class in just that. The art in there is a warm invitation to keep turning the pages. The book is accessible and clear and perfect, a real work to give the world.”

In the mailbox a week later, I received his new book, Falling, and a request I review it—I’d just experienced a twinkle of his sense of humor.

Falling was totally unexpected, like hearing first-hand over a beer the author’s favorite stories about the singular danger inherent to his trade: “unimpeded gravity.” But he steered away from gruesome tragedy and towards characteristic wit. Brion wanted readers to “learn from the mistakes and misfortunes of the fallen,” not to “fixate on the fall itself.” And so this book is direct and also waxes philosophical, and I liked it very much. After my review ran, I received a card in the mail from Brion. He was full of hope that the “five-week course of zappage” he’d undergone had pulled him out of the woods. He expressed a renewed interest in writing the article we’d talked about.

Then he was gone.

I’ve since learned more about Brion, much from Carol Hasse, the master sailmaker in Port Townsend, Washington, whose loft has been within throwing distance of Brion’s shop for nearly 40 years. Carol describes a friend with unbounded mirth, who loved puzzles and sought levity in every situation, and never at the expense of others. She’s mourning a raucous laugh she’s used to hearing boom across the harbor regularly. She told me that Brion was working on a book when he died, working hard to finish it. She assured me the book was coming, to be finished by Ian Weedman, the rigger who has worked for Brion for decades, the rigger Brion trusted to carry on his business.

I learned that Brion wasn’t a sailor turned rigger, he was a young guy fascinated with knots who saw rigging as a trade that would let him tie more of them. Even after he embraced the trade and came to spend more time on sailboats than many of us, Brion wasn’t passionate about sailing, he was passionate about the practical role his work played in creating the beauty he saw in a yacht under sail.

Maybe you’ve met people doing what they’re born to do? People who early on embraced a vocation that was perfectly aligned with their interests and aptitudes? Not only are these folks usually the best in their chosen fields, they’re also happy and balanced—at peace. By all accounts, that was Brion Toss.

Michael Robertson is Good Old Boat’s editor.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com