Hot springs and cool sailing help accomplish the goal to circumnavigate Vancouver Island.

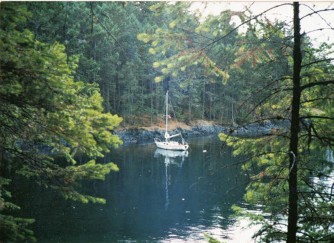

Dreamer at anchor in a sparkling Bottleneck Cove.

Issue 136: Jan/Feb 2021

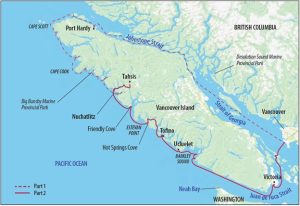

By the time my wife, Carey, and daughter, Nicky, met me and Dreamer in Tahsis on Vancouver Island’s west coast, my circumnavigation was more than halfway completed. I had already navigated safely past the first four of the 700-mile-long voyage’s most challenging hurdles: Johnstone Strait, Nahwitti Bar, Cape Scott, and Cape Cook (aka the Brooks Peninsula).

I’d enjoyed the most exhilarating sailing I’d ever experienced, rounded majestic and daunting headlands, walked remote beaches with only the company of bear tracks and bald eagles, and met some truly kind people along the way who’d helped me out of a few minor equipment jams. Now, only two more hurdles stood between Dreamer and the end of our trip in our home port of Tsawwassen: Estevan Point and Juan de Fuca Strait.

Bert’s wife, Carey, enjoys the eponymous springs at Hot Springs Cove.

I was excited to introduce Carey and Nicky (who’d arrived along with our two cats, Bozo and Nifty) to real ocean sailing and to continue exploring this bold and beautiful coast with them.

After provisioning with fresh supplies, we made an early morning departure and sailed to the anchorage in Nuchatlitz Inlet. As ocean waves crashed against the rocky shore, the low-lying isthmus protected us to the point of absolute stillness.

Nuchatlitz Inlet was the traditional summer home of the Nuu-chah-nulth First Nations people for hundreds of years. Photographs taken as recently as the mid-1980s show a cluster of houses, a wharf, and a fish processing plant on the opposite shore. On our visit, only a few sparse cabins still stood, along with bits of foundations beneath tall grasses and what remained of the processing plant—rotting pilings jutting from the water. We learned the site is a protected provincial park accessible only by boat or float aircraft.

Sailing further south, we rollicked in more than 20 knots of wind under blue skies, surfing down massive blue waves and pegging the knotmeter at 10 knots, then plunging into troughs and hoping each time that the bow would rise to meet the back of the next wave (it always did).

Having already experienced sailing much like this during the first part of the trip, I was having a ball; unfortunately, neither Carey nor Nicky felt the same. Carey refused to take the wheel, gripping the lifelines and whatever else was handy. I’d offered Nicky motion sickness medication before we hauled anchor, but she’d declined and instead made a bucket her best friend for the afternoon. Both of them endured their discomfort with positive attitudes and smiles, but neither seemed interested in hearing me regale them about the raucous sail I’d just survived north of the Brooks Peninsula.

The dock at Hot Springs Cove sports an eclectic assortment of vehicles, including Dreamer and the float plane that flew tourists in from Tofino.

The payoff was Friendly Cove in Yuquot (formerly Nootka Sound), a National Historic Site. Perhaps Captain James Cook felt the same relief when he pulled in here 243 years ago, but unlike him, our first landmark was the Nootka Lighthouse. Built in the 1950s to replace the original 1911 wooden tower, it dominates a rocky outcropping overlooking the anchorage. We toured the facilities with Ed Kidder who, along with his wife, Pat, had been on station for 20 years and they were happy to greet visitors. I was fascinated to see that the original 1950s-era weather-monitoring equipment was still in use alongside more contemporary gear.

We also visited the 132-year-old chapel on First Nations land at the head of the cove, being granted permission by a friendly giant of a man running a lawn mower over a knee-high meadow of grass. A traditional potlatch, hosting up to 17 local First Nations groups, was set to begin in a few days, and the field needed clearing. The chapel, still used for special occasions, retained the original stained-glass windows donated by the Spanish Government in 1957 to commemorate the Nootka Convention Conference of 1792. This historic meeting of Captain Bodega-Quadra and Captain Vancouver settled a territorial dispute between Spain and England.

Taking the advice of the lighthouse keeper, we sailed out of Nootka Sound at dawn a few days later. We had low-lying Estevan Point to clear and wanted to do so before the wind clocked more westerly in the afternoon, forcing us to tack to windward. Judging distance off the extensive shallows and reefs of this point was difficult at the best of times. With the prevailing southerly currents, there was the added danger of being swept towards the shallows. A few years earlier, an experienced, well-known local sailor and his son aboard Pachena, a 50-foot, cold-molded racing sloop, foundered on these reefs with tragic results.

At Bamfield, the crew hightailed it for the west side boardwalk in search of ice cream at the general store.

Our fate was far better. Under a warm sun and on a tight reach in more than 25 knots, we flew over cresting seas with Estevan Point visible in the distance, safely clearing the shallows to port before turning south onto a broad reach. Despite the fabulous sailing, the remaining 31 miles to Hot Springs Cove were damp and cold in the ocean wind, the warm sun hidden by the sails. I thought it was another great sail—Carey and Nicky weren’t as thrilled. But hurdle five of this circumnavigation was under the proverbial belt, and I couldn’t have been more pleased.

Tying up to the docks in Hot Springs Cove, Carey and Nicky noted pointedly that the local commercial fishing fleet had stayed in port due to the high winds and heavy seas. We did score some fresh halibut for dinner from our new fishing friends.

Of course, a highlight of Hot Springs Cove is the hot springs. From shore, a one-and-a-half-mile trail and boardwalk lead to springs that fill pools with hot water and fill the air with the characteristic smell of sulfur. The wood-planked stairs and boardwalks make easy work of more difficult sections of the trail, and many of the planks are engraved with boat names and dates. Some were so weathered and worn they were difficult to read, others glowed with fresh varnish. We delighted in coming across the names of friends’ boats, but without any woodworking tools we couldn’t add our own.

Having pictured these famous springs from reading, we were surprised to see bathing ponds much smaller than we’d imagined. The springs are a cascade of pools formed by arranged stones, each lower than the previous, all the way to the ocean. The closer a pool is to the hot springs, the hotter the water. In the lower pools, high tides and the occasional wave would send icy seawater into the warm pond, a real bathing experience. Unfortunately, the pools were also full of afternoon tourists and fishermen. We planned for an early return the next day.

It’s easy to see how Race Rocks and Race Passage in Juan de Fuca Strait got their names.

The following morning, we had the springs all to ourselves. Relaxing with soap and shampoo at hand, we watched humpback whales feeding in the ocean only yards from shore. From the dock later that day, we saw float planes and tour boats loading and unloading visitors from nearby Tofino, all bound for the springs. Once again, I felt privileged and fortunate to be able to explore this gorgeous, wild coast on my own schedule and on my own boat.

By sail rather than float plane, we arrived in Tofino a few days later. It was an abrupt change from the solitude to which we’d grown accustomed. The town of about 1,000 permanent residents has a public dock with limited space for transients, all of it filled by the commercial fishing fleet. The town itself is tourist-oriented, catering to whale watchers, surfers, hikers, and those seeking transportation to the hot springs.

A 25-mile stretch of rocky coastline and sandy beaches separates Tofino from Ucluelet, the next enclave of civilization south along the outer coast. We sailed there to provision for our planned Barkley Sound exploration. We found large, accommodating public docks and a more working-town setting; absent were the tourist trappings of Tofino.

Locals recommended Matterson House as the place to get a great meal. An ordinary, unpretentious small house on the main street, Matterson House had been converted into an officers’ mess during World War II, catering to troops stationed in the village operating a nearby radar station. Since the war ended, a succession of owners has maintained the house as a restaurant. Sitting in the cozy living room and enjoying a meal for which no preparation or cleanup was demanded was a treat and the perfect prelude to heading into the wilds of Barkley Sound.

The coastal steamer Frances Barkley makes her rounds in Barkley Sound.

Penetrating 15 miles inland and about 14 miles wide, Barkley Sound is a cruising sailors’ paradise, dotted with islands and secure anchorages. Like the rest of the west coast, westerly winds would start around 10 a.m., building to 15 knots or more in midafternoon, before easing to a calm at sunset. The clear waters reflected the dazzling blue skies and green islands. Deer wandered the forests, bears scoured the beaches, and eagles soared overhead. Despite our lack of fishing skill, we hooked a salmon by simply dragging a hoochy on a line over the stern.

For a week we sailed short hops between anchorages, everything from warm, tranquil inland coves to windy, boisterous bays out near the coast.

On the south edge of Barkley Sound is the village of Bamfield, separated on two shores by narrow Bamfield Inlet. The east side of the village had road access and is still the western terminus of the West Coast Trail. The west side, accessible only by water, featured a meandering boardwalk along the water’s edge connecting the village houses to a general store and post office and ending with a Canadian Coast Guard training and response station. During the stormy winter months, training here is focused on small-craft handling close to rocky shores in mountainous seas—not for the faint of heart.

A trail from the village boardwalk leads to Brady’s Beach, one of the most photographed beaches on Vancouver Island’s west coast. The beach faces northwest into Barkley Sound as well as to the open sea. Summer sunsets illuminate rocky spires on white sandy beaches.

A misty morning in Turtle Bay, Barkley Sound.

After sailing Barkley Sound, it was time to tackle Juan de Fuca Strait (historically identified as The Straits of Juan de Fuca, but labeled Juan de Fuca Strait on charts). This 60-mile stretch of open water, 12 miles wide, separates Vancouver Island from Washington State. With a constant stream of international commercial traffic destined for Canadian and American ports, the U.S. Coast Guard operates a maritime traffic control system similar to the air traffic control system used to guide aircraft through congested air space. Recreational vessels can radio in, get identified on radar, and then be given traffic alerts and course headings away from live-fire military exercise zones when in use. It seemed like an appropriate gauntlet for the final hurdle in our circumnavigation.

The strait begins at an imaginary line that connects Port San Juan on Vancouver Island’s southern tip and Neah Bay on the northwest corner of Washington state. The last 30 miles of the island’s Pacific coastline northwest of the strait is an exposed stretch that comprises the northern edge of the Graveyard of the Pacific. These treacherous waters continue 200 miles south, to just beneath the mouth of the Columbia River, which is the border between Washington and Oregon. Thousands of ships have been lost here since men took to the sea. This northern part is especially dangerous when the outgoing current from the Juan de Fuca Strait meets a strong Pacific westerly. In fact, the West Coast Trail portion of the Pacific Rim National Park—a popular hiking trail today—was constructed in the early 1900s for rescuers to gain access to shipwreck survivors.

At night, the Victoria waterfront was lit up like a holiday.

Once inside the Juan de Fuca Strait, currents are a significant factor. At Race Passage near Victoria, tidal currents reach 6 knots. Sailing inbound on the strait, we hoped for a westerly to build as the day progressed to give us a sleigh ride, and we planned carefully to reach Race Passage on the inbound flood, smoothing out the expected seas and helping us toward Victoria.

We were fortunate, again. At 5:00 a.m. on a calm, sunny morning, we raised anchor and began the long inbound trip from Cape Beale. We motored for hours over glassy water before a light breeze rippled the waters from astern as we passed east of Port San Juan. The much-hoped-for westerly had arrived! The spinnaker was again pulling us, this time toward Victoria, as ripples turned to waves. Excitement aboard peaked when a large pod of orcas raced towards us from dead ahead, the powerful animals approaching within yards.

When whitecaps appeared, we fought the spinnaker into the cabin. Under main and jib, we sped towards Race Passage, surfing for short distances. Five knots of favorable current boosted us to heady speeds over the ground as we flew by the Race Rocks Lighthouse and turned the corner towards Victoria Harbour.

The air temperature rose dramatically, relieving us from the cold, damp wind of the strait. By 5:00 p.m., we were tied up to the visitor dock in front of the stately and famous Empress Hotel, the heart of downtown Victoria. We’d completed the last hurdle of our circumnavigation!

From the cockpit, we tried to take it all in. Along the granite causeway, buskers entertained hordes of tourists and locals. Bozo and Nifty quickly jumped ship, rolling onto their backs and stretching on the concrete dock.

When we felt somewhat acclimated, we wandered the downtown, visiting the famous Dutch Bakery for pastries, the massive stone Provincial Legislature, and the Royal B.C. and B.C. Maritime museums, all within just a few blocks of where Dreamer safely rested. Back on the boat later, we listened to live music played on the causeway while basking in the glow of a spectacular sunset.

My family and crew had trusted me to keep them safe, and as boisterous as parts of the trip had been, my planning and judgment had not failed us. I tipped my hat to the sturdiness of the old Islander Bahama 30. I know from accounts of others that Lady Luck dished us a fair hand with plenty of favorable winds and seas. I soon had the opportunity to give back.

During the three days we spent before the Empress, we kindled a friendship with an American couple aboard a Newport 30. They were new to sailing and had just crossed Juan de Fuca Strait for their first visit to Victoria on their own keel. We had a chance to guide them farther, into the waters around the Gulf Islands of the Salish Sea, our backyard, as we sailed home to Tsawwassen through Active Pass and across Georgia Strait. We’d completed our Holy Grail.

Bert Vermeer and his wife, Carey, live in a sailor’s paradise. They have been sailing the coast of British Columbia for more than 30 years. Natasha is their fourth boat, following a Balboa 20, an O’Day 25, and another Islander Bahama 30 Dreamer. Bert tends to rebuild his boats from the keel up. Now, as a retired police officer, he also maintains and repairs boats for several non-resident owners.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com