Outboards are an easy way into electric propulsion, but are they for you?

Issue 143: March/April 2022

For the last 15 years I’ve been telling myself my next outboard might be electric. If I had a small dinghy I lifted on deck every night, perhaps I would buy one. But for a dinghy on davits or a small sailboat, I’m not yet seeing it. I compare the specs, look at the track record, and ask myself, “Why I would pay more for less?”

My next car will likely be electric. But the problem with boats is energy density. My car (a Mazda3) gets 43 miles per gallon (mpg) at 60 mph. My F-24 weighs three times less and gets about 12 mpg at 6 knots. The difference is that cars practically coast once they get up to speed, particularly streamlined models, but boats are constantly pushing up a hill of water unless far below hull speed, and waves only make this worse.

So, while I’d love the quiet on protected waters that an electric outboard affords, I’d miss the power and range a good four-stroke gas outboard provides on more open waters.

In other words, I’m still waiting, but that said, let’s look at how electric outboards stack up.

Because of differences in prop design and rpm, electric outboards typically have more low-speed thrust, but they’re slower than equivalent gas outboards at the top end. Boat tests and user reports agree that electric motors with the same rated equivalent horsepower are slower than gas outboards; often the rationalization accompanying these results is, “But they’re so quiet.”

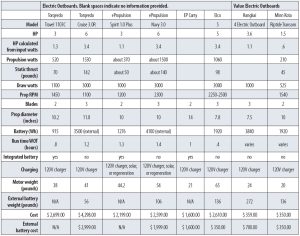

In general, manufacturers overstate effective horsepower; the horsepower calculated from motor watts (a simple conversion factor) and typical electric motor efficiency (85 percent) is, give or take, about half of which the manufacturers claim. The propellers appear to be more efficient, so two-thirds of the claim seems to match both the math and product reviews. Given this information, I suggest de-rating effective horsepower claims by about a third; in other words, a 6-hp electric motor would be equivalent to a 4-hp gas outboard.

Electric outboard propellers tend to be a bit larger in diameter, higher aspect ratio, and run at lower rpm. This increases efficiency at low boat speeds, but at higher speeds, where cavitation and ventilation are factors, conventional prop designs still rule.

Direct-drive electric outboards are quieter because the motor is underwater and there are no gears. The tradeoff is increased vulnerability to corrosion and a general reduction in total life expectancy versus conventional gas outboards.

Charging

Unless they plug them in ashore, sailors need the ability to recharge their electric outboard motor batteries from the main bank. ePropulsion motors have a separate input for solar charging, but unless you’re powering a small boat on a mooring, most likely the panels will be connected to the mother ship.

As a practical matter, all will be charged using a dedicated 120-volt charger run off an inverter. Unavoidably, recharging adds strain to both battery capacity and charging energy sources. You’ll probably need more solar or wind if you plan to charge from the mother ship, rather than plugging in ashore.

When cruising, we typically use about 1/3 tank (one pint) of gasoline per day in my Mercury 3.5 dinghy motor. Some days it might be as much as 1/2 gallon, sometimes only a few ounces, but in general, I top it off every other day. I estimate this is equivalent to about 1/2 charge on a self-contained electric outboard, about 500 Wh (watt-hour), or about 50 Ah on your 12-volt battery bank, after inverter efficiency and charging hysteresis are factored in. For my needs, this would mean I’ll require an extra 100 to 120 watts of solar and one to two more house batteries to power my dinghy with an electric outboard equivalent to my 3.5-hp Mercury.

My F-24 has a 4-hp Honda and a 3-gallon external tank. Though I use the motor only to exit the harbor and manage sails, I seem to go through about 1/2 gallon each daysail. This is twice the requirement of the dinghy we just discussed, or about 100 Ah on a 12-volt bank. Assuming five hours at 100 percent rated output (an accepted industry estimation of solar output), it will require 200 watts of solar panels just to keep the motor charged, and six to eight hours to accomplish the charging.

For this little bit of maneuvering usage, I’d need to add two to three batteries, and running multiple days without recharging is a risk. If the wind dies on day two, we’ll just have to wait until it returns, and we’d better earmark a reserve for harbor maneuvering. Running a generator to charge is possible, but ironic.

ePropulsion offers hydrodynamic charging—putting amps back into the battery at the cost of drag and slower sailing. I question an outboard prop’s ability to stay solidly in the water in the sea conditions required to provide excess sail power for charging. I can see it with a pod drive, but for outboards, I’m skeptical, judging from the way they bounce up and down in waves. I’d rather squeeze in one more solar panel. Still, this option could help smaller boats that are limited by hull speed and lack sufficient space for solar.

As for batteries, a few of the manufacturers—Elco, Hangkai, and Minn Kota—recommend lead acid batteries, because they still offer the best ratio of dollars per unit capacity. They remain the standard for industrial forklifts and solar installations. But they are heavier, cannot be cycled below about 40 percent state of charge without serious lifespan reduction, don’t last as long, and charge more slowly. Installed low in the bilge of a displacement cruiser, a few lead acid batteries won’t hurt a bit. But for a light dinghy or sport boat, lithium is the better answer.

An Outboard Sampling

Below is a sampling of electric outboards on the market. I’ve only used the Torqueedo and EP versions, but I’ve talked to people who have used or have tested the rest.

EP Carry: Dubbed the electric paddle, it is light, less powerful, competitively priced, and earns good reviews. I’ve only used it once, and though it was not powerful, it moved a small hard dinghy well in the harbor and was light as a feather. Compared to a trolling motor, it is far more user friendly. It’s the best choice if you value easy handling and don’t need power.

Torqeedo: This is the best-known manufacturer, with the longest track record for self-contained electric outboards, though a less-than-enviable reliability record. The original Travel was plagued with a variety of mechanical and electrical problems. The redesigned Travel 1103 C switched to a direct drive, like a trolling motor, and seems to have solved many of the original’s problems, but I am still hearing some complaints and doubt they will match the 10- to 20-year life expectancy of a well-cared-for gasoline outboard. Corrosion will get to something, the plastic parts will crack, and certainly the battery will need to be replaced. In their favor, however, is quiet and simple operation.

The Travel models use integral batteries, and the Cruise line uses external batteries. All use direct drive. The Cruise line requires the installation of a remote throttle. Torqeedo also makes saildrive and shaft-drive inboards.

ePropulsion: At first glance, this is a Torqeedo look-alike, but it’s not a clone, and the engineering is different. Though only on the market for six years, we’ve heard few reports of trouble. For example, the Spirit has sturdier electrical connectors, more range, and faster charging. The 6-hp Navy 3.0 is available with a tiller, eliminating the need for a remote throttle and allowing direct steering for tight maneuvering. Like Torqeedo, ePropulsion also makes pod drives up to 6 kW. Pricing is 20 to 35 percent less than Torqueedo.

Elco: Long established, Elco has been building electric drives for 130 years, well before electric was cool. Mostly, I’ve seen shaft-drive inboard units in launches and taxis. The 5-hp is based on a proven Yamaha gas outboard frame, and Elco knows how to make durable electric drives. It’s not light, and the recommended lead acid batteries drive the total weight even higher, but you can expect reliability and solid performance. This is perhaps the best choice if easy portability is not important.

Below are what I call “value” electric outboards.

Minn Kota: This company has been making trolling motors since before I was born, and for the most part, they last. The Riptide is a transom-mount saltwater version, so it should stand up to corrosion, but don’t expect a lot of oomph on open water. Like the EP Carry, it is a good harbor motor and cheap as chips, but not as user friendly because of the external batteries.

Hangkai: They make a 4-hp electric for a bargain price. A fellow down the dock from me got one last spring, paired it with some batteries he got for free when a yacht repowered with lithium, and for under $400, he’s scooting around the harbor in good style. In a few years, we’ll know more about durability.

In the end, it boils down to personal needs and wants. For me and my needs, it’s hard to top a gasoline four-stroke outboard. Honda and Tohatsu (which makes small outboards for Mercury, Evinrude, Yamaha, and Nissan) are the standard for comparison; I’ve had all of them. Feed them clean gas (keep the vent closed when not in use, turn over the gas by sailing often, and use a quality anticorrosion additive), and they run and run.

They are louder than electrics and vibrate more, they are slightly heavier than the self-contained electric outboards, but they are lighter in larger sizes when the external battery weight is included and have far greater range if an external tank is attached. Even a 1-liter aluminum fuel can under the seat adds considerable range and backup safety. In my opinion, these remain a better solution for larger boats and dinghies that will take longer trips or cross open water.

Good Old Boat Technical Editor Drew Frye draws on his training as a chemical engineer and pastimes of climbing and sailing to solve boat problems. He cruises Chesapeake Bay and the mid-Atlantic coast in his Corsair F-24 trimaran, Fast and Furry-ous, using its shoal draft to venture into less-explored waters. He is most recently author of Rigging Modern Anchors (2018, Seaworthy Publications).

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com