During a seven-day rally,

the Salish 100 celebrates the vivacity of small boats.

Issue 145: July/Aug 2022

Usually, I’m better prepared. Self-recrimination rarely does any good, but as I fumbled to stuff AAA batteries into my portable running lights while vaguely tending the tiller of Surprise, my Sanibel 18, better-sailed boats ghosted through the foggy circle of my vision, and I cursed myself for not having everything ready before leaving the slip. We were headed out of Ludlow Bay on Puget Sound when the typical light marine layer had become dense fog, and now I was threading a needle between Snake and Colvos rocks, scrambling to get my radar reflector and running lights in place.

I’d already dashed below, desperately rummaging for the running lights in the by-now-totally-disorganized navigation bin. After several minutes of futile searching, I’d popped my head out of the companionway and realized we were headed for some submerged pilings to port. Lightweight sailing craft are very sensitive to weight shifts! I’d jumped back into the cockpit, reset our course, adjusted the sails, lashed the tiller, and returned below to continue the excavation.

Finally successful, I clipped my tether to the port shrouds and crawled forward on the slippery deck to lash the lights to the pulpit. Creeping halfway back, I grabbed the radar reflector and hoisted it with the spare jib halyard. Just in time, too, as the fog-muffled tolling of the Klas Rock bell buoy dead ahead ominously reminded me to remain alert.

So began the final day of one of my most enjoyable cruising adventures in 65 years of avid boating. Surprise and I were participating in the second annual Salish 100, organized by the Northwest Maritime Center of Port Townsend, Washington. After a one-year pandemic hiatus, in July 2021 more than 100 small-craft enthusiasts were sailing in the 100-nautical-mile cruising rally through the Salish Sea from Olympia to Port Townsend. Along the way, we experienced 10-foot-plus tides, currents topping 5 knots, tidal rips, fog, fast ferries, ship traffic, and the fickle winds and unpredictable weather of a Pacific Northwest summer.

It was my first time at this event, whose first rule—don’t have too many rules—appealed to my sense of whimsy and discernment. Waterborne craft of any description under about 23 feet and powered by sail, oar, paddle—even a small motor—or any combination thereof are eligible. If your boat is too large or too powerful, you can volunteer to participate as an escort vessel, shepherding the small fry. Entrants must certify that their craft can maintain an average speed of 3 knots, whatever the conditions, to make each day’s march. Failing that, they’ll be ignominiously towed into port by a support boat.

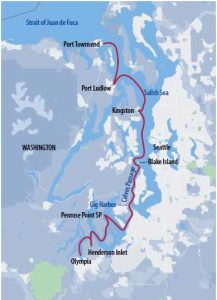

The route begins in Olympia, the southernmost end of Puget Sound (and the Salish Sea, which stretches north into British Columbia) and travels basically north to end at Port Townsend on the Olympic Peninsula. Each day’s 10- to 16-nautical-mile passage ends at overnight stops in Henderson Inlet, Penrose Point State Park, Gig Harbor, Blake Island State Park, Kingston, and Port Ludlow.

Before I could take on these navigational challenges, though, I had to survive the most nerve-wracking and perilous part of the voyage—towing Surprise from my home on Whidbey Island through Seattle and Tacoma traffic on terminally congested Interstate 5. I arrived with relief at Swantown Marina in Olympia, where the launch area and guest docks were already aswarm with tiny boats and their crews, many of them obviously old friends.

Mini-Boat Mecca

The next day, boats continued to pour in from all over. And what a collection of small boats it was! As one would expect in the Pacific Northwest, beautiful and unique wooden boats of all descriptions graced the docks, but so did great examples of classic production fiberglass craft.

Many of the wood/composite boats, often owner-built, had been designed by such notables as Welsford, Devlin, Oughtred, Stambaugh, Gartside, Henrickson, Hvalsoe, Short, Chesapeake Light Craft, and others. Most were open, camp-cruising, row-and-sail craft, but a few unique powerboats and several elegant coastal cruisers were also in evidence in the wood/composite fleet.

Among the fiberglass boats were 1970s-era small cruisers, including Montgomery 17s, a Montgomery 16 Katbote, Montgomery 15s, West Wight Potter 15s, a West Wight Potter 19, two Kent Ranger 20s, a Sea Pearl 21, an O’Day Mariner, a Balboa 21, a North American 23, a Flicka, and a Venture of Newport. Gig Harbor Boatshop’s SCAMP and a Sage 17 rounded out the fiberglass fleet, while unusual entries included a solar-powered electric boat, a spritsail proa, a sleek rowing shell, and even a competition paddleboard fitted with a dry bag.

That evening, the first and only organizational meeting laid out a general daily plan: morning roll call of boats, then get to the next stop however you can and anchor or moor as you see fit. Repeat seven times. If you get into trouble or leave the fleet, call on the VHF. Have fun. And that was it. Amid the happy, friendly, relaxed crowd, I felt immediately welcome, even though I had only known one other person there before my arrival.

The next morning dawned with light winds, but a favorable northerly current would help, as it would for the entire week. I congratulated myself on slipping out early and hoisting sail, pleased that Surprise could make way, if only barely, in the light breeze. However, I picked the wrong side of Budd Inlet, and soon most of the boats had passed me.

“Hmm,” I mused, “get used to it, Ferd. You and your boat are not really competitive in this fleet!”

Finally straggling into Henderson Inlet 11 miles from Swantown, I anchored, raised the bimini, and ate my one-pot dinner in relative comfort. That is the upside of my chubby but comfy boat. Friendly chatter from the smaller open boats camped in a gaggle along the shore murmured across the still water as I drifted into a

peaceful sleep.

The next day, awakened by roll call on the squawking VHF, I leapt into adrenalin-fueled action with barely time to make oatmeal and coffee. No more oversleeping! Once underway, a tiny but skillfully sailed SCAMP passed us, so I eventually gave up and used Tohatsu-assist to transit wide Drayton Passage, followed by tortuous and narrow Pitt Passage, finally picking up a mooring ball in Mayo Cove. My only consolation was learning that almost everyone else had motorsailed or rowed as well—even that SCAMP, which I discovered had a stealth electric outboard.

The smaller boats made for the park docks or beach, the rest moored or anchored out. The pace of social life picked up, and a sunny afternoon with a decent breeze inspired some to daysail around the cove. Impromptu sails are one of the real pluses of small, easy boats, but I lazily chose to retain possession of my mooring ball. The predicted 15-knot nocturnal winds failed to show, and it was another quiet night for all.

On day three, I got underway early in hopes of minimizing my humiliation, sailing across Carr Inlet to pass north of Fox Island. The wind picked up a bit, and I was leading most of the fleet for once, making almost 5 knots with a lovely current assist as I passed under the Fox Island Bridge. The breeze dropped as I turned north toward Galloping Gertie, the infamous Tacoma Narrows Bridge, so I started my outboard for insurance, motor-sailing at a slow idle while hugging the east shore for the fastest ride.

We blasted under the bridge at more than 8 knots and swung westward toward the dogleg entrance to Gig Harbor. I had furled my sails in preparation for entering, but just as we nosed into the tight channel, the Tohatsu packed it in and refused to restart. I quickly unfurled the genoa, thanking the gods that the wind was favorable, and sailed toward a sleek 40-foot sailboat anchored midway on the packed harbor’s north side, dropping my hook just off his starboard quarter.

Doubtless concerned for his topsides, the owner came on deck and watched as I pulled off the outboard’s cowling. Noting that gasoline poured out of the carb each time I squeezed the bulb, I suspected a stuck float was the culprit. I gave the carburetor a smart whack with a crescent wrench, and the owner’s expression was priceless at the Tohatsu’s start on first pull. I thanked him for the loan of real estate and proceeded to anchor in good company with a Navigator and San Francisco Great Pelican in the shallows, as only we skinny-draft boats can do.

Finding Family

The next morning, I powered out of Gig Harbor with the fleet, then sailed with a north-flowing current and fair wind. With a decent breeze abaft of beam, Surprise was more competitive, and we hung with the fleet leaders all morning. It was wing-and-wing until we reached the Southworth ferry terminal, where I peeled away to pick up a mooring ball off the west side of Blake Island, finishing the beautiful, all-morning sail.

I noticed a lovely Devlin boat, a 15-foot Nancy’s China, looking for anchorage, and invited James Thomas to raft up. He did, and we chatted about his adventures building the boat—as well as my life story, I’m afraid. Dennis Wang, in his handy escort boat Moon Lady, swung by asking if anyone wanted a run ashore, and James hastily agreed.

When he returned, we were surging up and down so much that I had been fending his boat off. James is an engineer, so he tried valiantly to rig our fenders to avoid damage to his beautifully finished brightwork, but finally gave up and left to anchor solo. It had been a fun, if brief, interlude in an otherwise solo passage so far.

As day five dawned, the typical early-morning marine layer was up at the tree-line, and a southwesterly of about 4 knots got me going under sail right after breakfast and ablutions. I fired up the Tohatsu to quickly cross the track of the fast ferries that blast out of Rich Passage headed for Seattle. Ferry stress took the place of a second cup of coffee, but once past Restoration Point, I killed the engine and sailed northward along the east shore of Bainbridge Island, well inside the southbound shipping lane. As the wind freshened from the south, the sailing was so good that the escorts were fully occupied nudging overly enthusiastic skippers out of the danger zone.

Along the way, the fleet encountered the 133-foot gaff-rigged schooner Adventuress, and I had a gangbuster time chasing her deep into Port Madison and racing back out again to join the fleet. Need I mention that I never caught her? Still, it was the most exciting and energetic sail of the trip; I don’t know why nobody else came along!

In Kingston, the jovial dockmaster and his friendly crew found a spot for everyone, packing as many as six of our small boats plus dinghies (yes, several boats towed dinghies, or at least floats) into one standard boat slip. It was my first step ashore and a very welcome one. I had a shower, dumped the dangerously full

portable toilet, took a walk, and ate crepes and ice cream with Dennis Wang and Bill Ferry. Then we walked the crowded docks, swapping lies and brilliant insights with fellow cruisers. The more time I spent with this fleet, the more time I wanted to spend.

After motorsailing and dodging ships through most of the next day’s passage, I was happy to tie up again, this time at Port Ludlow Marina. The Northwest Maritime Center organized a much-appreciated barbecue, and we all ate, drank, mixed, mingled, recited doggerel, and exaggerated.

The last day of the rally began in the fog at Port Ludlow, and after bungling my exit with the frantic scramble for running lights, a bit of a breeze picked up, and the fog lifted some by the time I approached the southern end of the Port Townsend Canal. I motor-sailed the canal for control rather than speed, as we shot through with a brilliant following current and spit out past Port Hadlock toward our final destination.

Once across Port Townsend Bay, several boats went directly to the ramp to haul out, while the helpful and pleasant Boat Haven marina staff directed the rest of us to the linear dock (translates to “long walk”) for the night, where we spent a final evening trading stories.

In all my years of sailing small boats, I’ve rarely had as much fun as I did in the Salish 100. It was an ideal combination of camaraderie, small-boat sailing passion and skill, organization, and beautiful boats and geography, with plenty of fun and humor woven throughout. You can bet I’m already signed up for this year’s event—and this time, the running lights will be ready.

Ferd Johns is an 80-year-old architect who, after decades of cruising the Chesapeake Bay and Florida Keys, now sails out of Whidbey Island in the Pacific Northwest. Afflicted with small boat-itis for more than 65 years, Ferd has collected, reconstructed, and briefly sailed an embarrassing number of small plastic cruisers, mostly sail. His wife, Beth, prefers their 31-foot Camano Troll.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com