A longtime sailor ponders the seemingly human qualities of an obdurate outboard

Issue 151: July/Aug 2023

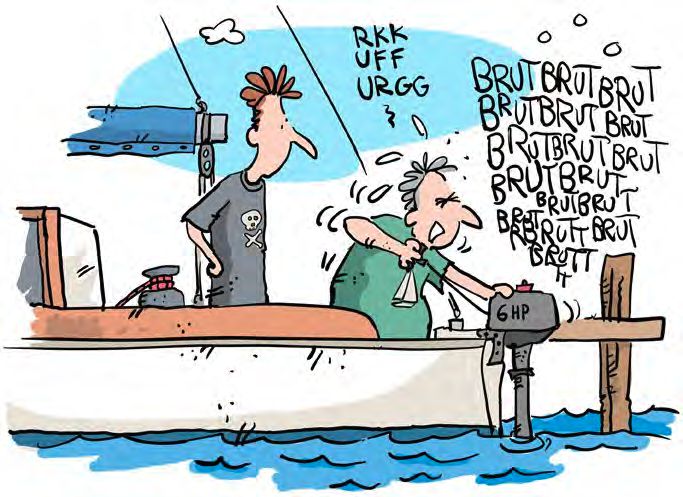

Over a long sailing life, I have found that there are times when, for no apparent reason, an outboard motor won’t run. This has led me to believe that outboards can be bewitched — and not only bewitched, but spitefully malicious.

As proof, I offer my experience with a 6-hp Tohatsu long-shaft four-stroke, which I bought brand new for my aged Santana 22 after industrious and extensive research. This little Japanese motor has an excellent reputation for reliability as an auxiliary for small boats. Everybody loves the Tohatsu, apparently, and it loves them back. So I bought one. Brand new, as I said.

I put it on the back of my boat, did all the things you are supposed to do before starting it, and pulled the cord. Nothing. I pulled again. Nothing. I stopped pulling to check everything I was supposed to do before starting, and pulled again. Nothing. My son Trent came along. “Let me have a go,” he said.

I put it on the back of my boat, did all the things you are supposed to do before starting it, and pulled the cord. Nothing. I pulled again. Nothing. I stopped pulling to check everything I was supposed to do before starting, and pulled again. Nothing. My son Trent came along. “Let me have a go,” he said.

One pull and it burst into life.

I bit my lip. We stopped the motor and I tried to start it. I tried and tried. Nothing. Trent tried and it started for him every time.

I wasn’t angry, just puzzled (well, perhaps a little angry). I thought the agent I bought it from should know about this. I grabbed the little Tohatsu by the scruff of the neck and bundled it off to the agent. They let me watch while a young mechanic put it in a large test tank. He pulled the cord and the motor burst into life. The mechanic looked at me and raised his eyebrows.

“Want to try?” he asked.

I tried. Nothing. I tried again. I nearly pulled my arm off. Still nothing.

The chief mechanic and others crowded around to witness this debacle. Thoroughly embarrassed, I said I would try it on the boat. I threw the motor in the trunk of my car and fled.

It was obvious that the motor hated me. It was obvious that it loved my son. So I gave it to Trent. I didn’t have much of an option. They are a happy couple now and I wish them well.

It was obvious that the motor hated me. It was obvious that it loved my son. So I gave it to Trent. I didn’t have much of an option. They are a happy couple now and I wish them well.

I have never had this sort of trouble before, not even with old outboards past their prime. My best-ever outboard was a 1975 6-hp Evinrude twin two-stroke — quiet, smooth, and powerful. Started every time. It had a great thirst for gasoline, a fault which, given its exemplary behavior otherwise, I was happy to overlook.

In view of all this, I was fascinated to learn that no less a person than Nobel Prize-winning author John Steinbeck regarded outboards as living creatures. In 1940 he took part in a biological expedition to the Gulf of California, collecting marine invertebrates. The expedition took along a skiff and an outboard. “It was intended that it (the outboard) should push us ashore and back,” he says in his book The Log from the Sea of Cortez. “But we had not reckoned with one thing … Life had been created.”

Steinbeck referred to the outboard as a Hansen Sea-Cow, a description intended to disguise the real brand name and fend off potential legal action. “Our Hansen Sea-Cow was not only a living thing but a mean, irritable, contemptible, vengeful, mischievous, hateful living thing,” he declared.

Steinbeck said members of the expedition had observed several traits in the outboard and were able to check them again and again:

- It was incredibly lazy. “The Sea-Cow loved to ride on the back of a boat, trailing its propeller daintily in the water while we rowed.”

- “It had apparently some clairvoyant powers, and was able to read our minds, particularly when they were inflamed with emotion. Thus, on every occasion when we were driven to the point of destroying it, it started and ran with a great noise and excitement. This served the double purpose of saving its life and of resurrecting in our minds a false confidence in it.”

- “It completely refused to run: (a) when the waves were high, (b) when the wind blew, (c) at night, early morning, and evening, (d) in rain, dew, or fog, (e) when the distance to be covered was more than 200 yards. But on warm, sunny days when the weather was calm and the white beach was close by — in a word, on days when it would have been a pleasure to row — the Sea-Cow started at a touch and would not stop.”

Steinbeck concluded, “Perhaps toward the end, our observations were a little warped by emotion. Time and again as it sat on the stern with its pretty little propeller lying idly in the water, it was very close to death. And in the end, even we were infected with its malignancy and its dishonesty. We should have destroyed it, but we did not. Arriving home, we gave it a new coat of aluminum paint, spotted it at points with new red enamel, and sold it. And we might have rid the world of this mechanical cancer!”

I must admit that my experience with the little Tohatsu was not as distressing as Steinbeck’s with the Sea-Cow. After all, the Tohatsu had some redeeming qualities. It loved Trent, for a start. And so far, it hasn’t played that wicked outboard game whereby it starts at first pull, inspiring the maximum of confidence, and then suddenly plays dead in the most dangerous bend on the way out of the marina.

I must admit that my experience with the little Tohatsu was not as distressing as Steinbeck’s with the Sea-Cow. After all, the Tohatsu had some redeeming qualities. It loved Trent, for a start. And so far, it hasn’t played that wicked outboard game whereby it starts at first pull, inspiring the maximum of confidence, and then suddenly plays dead in the most dangerous bend on the way out of the marina.

One of these days, I am going to sneak aboard Trent’s boat and see if I can take the Tohatsu by surprise. Maybe it will start for me. Maybe it will have forgotten to be mean to me. You never know. It’s only human, after all.

John Vigor is a retired journalist and the author of 12 books about small boats, among them Things I Wish I’d Known Before I Started Sailing, which won the prestigious John Southam Award, and Small Boat to Freedom. A former editorial writer for the San Diego Union-Tribune, he’s also the former editor of Sea magazine and a former copy editor of Good Old Boat. A national sailing dinghy champion in South Africa’s International Mirror Class, he now lives in Bellingham, Washington. Find him at johnvigor.com.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com