Starting in a garage, cousins Clinton and Everett Pearson initiated an era in yachting history

It’s a familiar story to sailing buffs. The Pearson cousins, Clinton and Everett, began the modern era of fiberglass production sailboats at the New York Boat Show, in January 1959, with the introduction of the Carl Alberg-designed Triton sailboat. They sold 17 of those 28-foot boats at the show, and “it started us chasing money,” says Clinton. Indeed, that one show put the fledgling company on the map and in solid financial shape, but this well-known story reveals only part of the roots of Pearson Yachts.

“The Navy ROTC sent me to Brown University,” says Clinton, “so after I graduated, I had to serve three years of active duty on the destroyer Joseph P. Kennedy. This was from 1952 to 1955. While on the Kennedy, I built a small model for an 8-foot fiberglass dinghy. Later, I built a mold for the dinghy in my father’s garage. I started the company in May 1955 with the $2,000 I received when I left the Navy.”

Clinton tried making the dinghies using a vacuum process. “But I had no luck with it after six or seven attempts. So I started making them from mat and resin in a lay-up in the garage.”

It didn’t take Clinton long to run out of money. He started working for an insurance company during the day and making the dinghies at night. But sales were promising enough for him to incorporate in early 1956. A high-school classmate named Brad Turner helped out by investing $5,000 in the business.

Clinton’s cousin, Everett, who was a couple of years behind Clinton at Brown, also served in the Navy after graduation. He worked with Clinton, building the dinghies when he could, and was able to come to the new company full-time in 1957. Fred Heald, a fellow Brown alumnus, joined them as head of sales.

At the request of customers, the cousins built larger dinghies, which they exhibited at the New York Boat Show in 1957. Sales were so good that the young company needed room to expand. The Pearsons found an empty textile mill on the waterfront on Constitution Street in Bristol, R.I., with a flexible lease that allowed them to pay just for the space they used. Soon they were renting the entire first floor. By the time of the show in 1958, they also were making 15- and 17-foot runabouts based on Clinton’s

designs, in addition to the line of dinghies.

Things started to gel in 1958. “A fellow named Tom Potter, who worked for an outfit called American Boat Building, over in East Greenwich, asked us if we would be interested in building a 28-foot fiberglass sailboat that would sell for under $10,000,” says Clinton. “Tom knew Carl Alberg, who was working at the Coast Guard Station in Bristol, across from where we were renting space. We agreed, and Tom had Carl design the boat for us. So Tom Potter was really responsible for the concept of the Triton.”

Big in Europe

Big in Europe

“I had an idea for a family cruising boat using fiberglass,” says Tom. “Family cruising was a big thing in Europe at the time, but not in the U.S. The idea hit me that we could do the same thing, and it would be successful if the price was under $10,000. Everyone was still building boats from wood, but I thought fiberglass was the way to go.” Building with fiberglass allowed for a much roomier interior compared to wooden boats.

Tom adds: “I approached a number of people about my idea. My employer at the time, American Boat Building, wasn’t interested. I talked to Sparkman & Stephens. They wouldn’t give me the time of day. I got to know Carl while I was at American Boat Building, and talked to him about the idea. He’s the one who introduced me to Clint and Everett. He knew they were building fiberglass dinghies and runabouts across the way from him and thought they might be interested in building a sailboat. Naturally they were. So Carl designed the boat, and I financed the tooling for it. Carl had been designing ammunition boxes for the Coast Guard when the Triton idea came along.”

The cousins built the boat and had to borrow money to truck the Triton to the 1959 New York Boat Show. They didn’t even have the cash between them to pay the hotel bill. The boat’s base price was $9,700. When it became an instant success, with $170,000 in orders, the hotel bill was paid, and the young company was off to a solid start.

“Right after the boat show,” continues Clinton, “we still needed money to build those 17 boats. We already owed the bank $6,000, and we had to go back to the bank to ask for even more. We asked for – and got – $40,000. That started us chasing money. From the very beginning, we had to chase sales to pay off loans, a never-ending process.

“Carl sold the Triton plans to us for $75,” states Clinton, “and then he wanted royalties of $100 per boat sold.” The Pearsons agreed to those terms, although eventually it would work against Carl.

Flush with the success of the January 1959 show, the cousins took the company public that April. “The shares opened at $1,” says Clinton. “They were $3 a share the next day. By the end of 1959, the price was $13 a share.”

Sales stayed strong enough for the company to add another production site. Pearson bought the legendary Herreshoff Yard in November 1959 for $90,000, half in cash and half in stock. Production also continued at the Constitution Street site in Bristol.

Clinton explains, “In 1959, the market was just right for us. The price [of the Triton] was right. Leisure time was a big thing. They were pretty simple boats to build at the time, and we tried to build one boat a day to keep up with the demand.”

Controlling Interest

In 1960, the Pearsons were trying to obtain approval for another stock offering, but had trouble getting the proposal through the Securities and Exchange Commission. The money chase was continuing, and the company needed another cash infusion to finance its rapid growth.

“Luckily, Grumman was there and interested in the company,” says Clinton. In 1961, Grumman Allied Industries bought a controlling interest in Pearson Yachts for $800,000. Grumman wanted to diversify its military-aircraft business. It already had an aluminum-canoe division as a toehold in the boating industry. Grumman sought a stake in the developing fiberglass-technology area, and Pearson was a leader in the field at the time. The Grumman purchase started a long period of growth and stability for the yacht manufacturer.

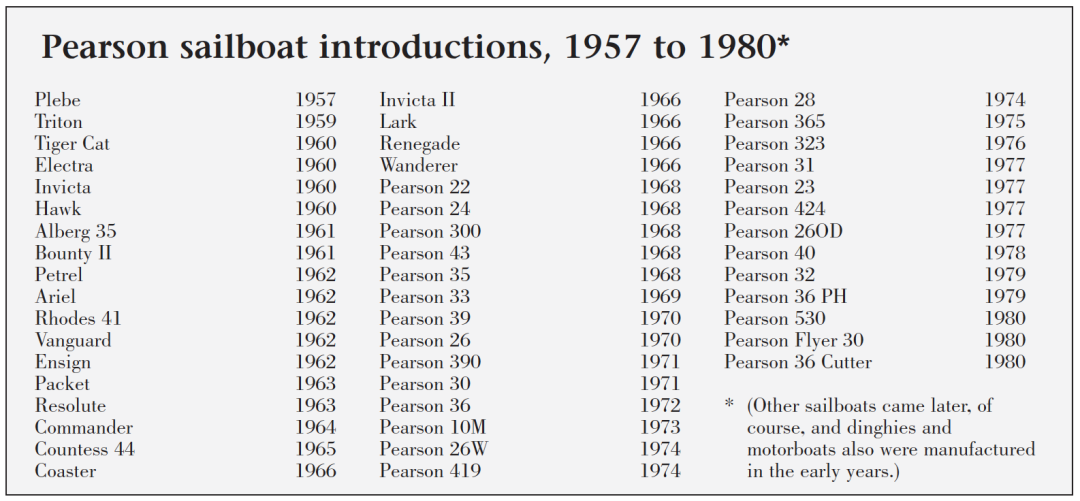

With the full backing of the new owners, the Pearson cousins expanded production to include more boats, both large and small. Most also were Alberg-designed boats. The 20-foot daysailer called the Electra, “which we made into an open 22-foot daysailer called the Ensign,” says Everett, was added in 1960. The Alberg 35 followed in 1961.

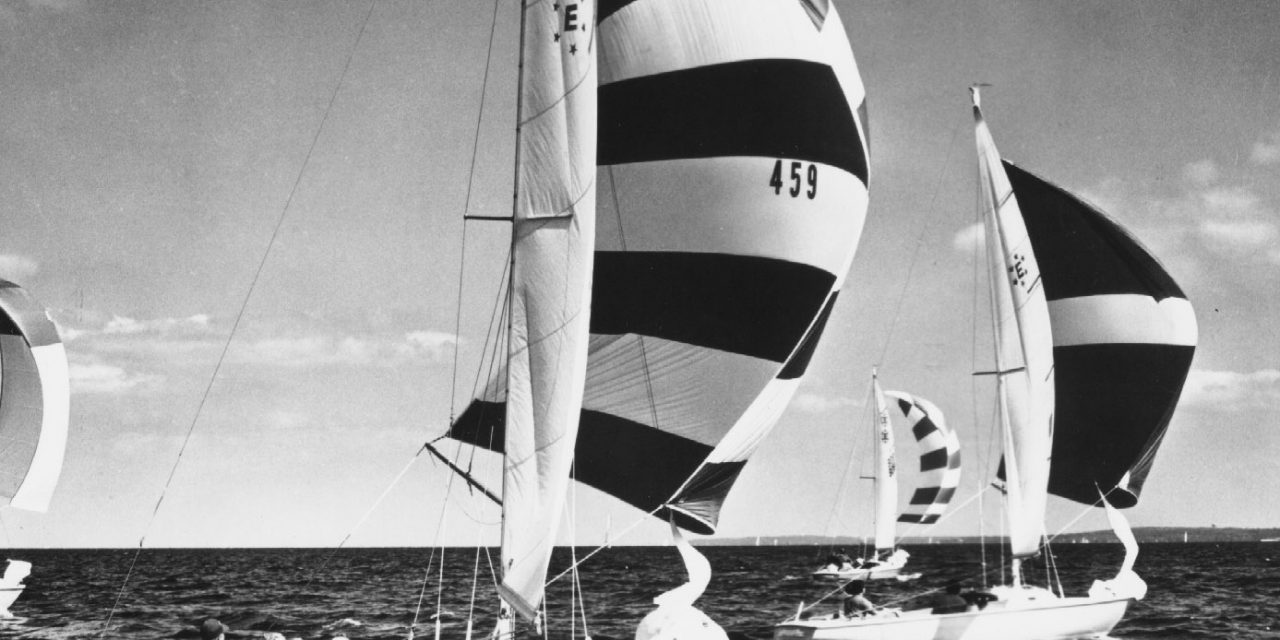

According to Clinton, “When we started building the Ensign, it was an exception [to the one boat a day goal.] We eventually got that line up to two a day, then three a day” to meet the demand. It became a popular one-design racer, with nearly 1,800 produced in its 21-year production run.

Other Alberg designs were the Rhodes 41, a 26-footer called the Ariel, and a 16-footer called the Hawk. Pearson also built the Invicta, a 38-footer designed by Bill Tripp, in the early 1960s. “It was the first production fiberglass boat to win the Newport-to-Bermuda Race, which was the 1964 race,” Everett says proudly. The young firm also produced powerboats, including the 34-foot Sunderland.

States Clinton, “A lot of credit for the early success of the company has to go to Tom Potter for selecting a line that would sell.” For his part, Tom says, “Fred Heald and I were close friends, and we ran the marketing end together. I primarily worked with the designers on boats we thought would sell, while Fred worked more on marketing the boats. It was a pretty exciting period of my life.”

As with the Triton, Carl Alberg received a royalty on each of his designs that was sold. “As the boats got more expensive, the royalties went up,” states Clinton. “By 1964, Carl was making $40,000 a year from us, on top of what he made from the Coast Guard. Grumman wasn’t happy at all with the royalties and said we should hire our own architect.” But first, Everett approached Carl about renegotiating the deal on royalties. “He was a stubborn Swede and refused,” says Everett. “So we had to say: ‘No more boats from him.’ ”

A Grumman employee named John Lentini had a hand in the next serendipitous step for Pearson Yachts. John had purchased a sailboat designed by the prestigious New York firm of Sparkman & Stephens. One of the naval architects involved in that boat was a young fellow named Bill Shaw, and he and John became acquainted. When Lentini learned of the opening at Pearson Yachts, he mentioned it to Bill, who went to Bristol, R. I., for an interview with the Pearson cousins.

Momentous Year

“I had worked for Sparkman & Stephens for 11 years before leaving to work for an outfit called Products of Asia, which also was based in New York,” says Bill. “It imported custom wooden yachts from Hong Kong, and I ran their marine division.” The company’s most famous import later on was the Grand Banks line of trawlers.

The interview went well, and Bill was hired as the Director of Design and Engineering with a starting salary of $18,000. “We hit it off,” says Everett. “It worked out very well.”

“Rhode Island was my home state, and I was thrilled to be able to return there,” he adds.

As it turned out, 1964 was momentous for Pearson Yachts for more than the hiring of Bill Shaw. Grumman financed the construction of a 100,000-square-foot manufacturing plant in Portsmouth, R.I., and planned to move the company there the following year. “Lots of people didn’t want to make the move,” says Clinton. “Plus, Grumman fired me in 1964.”

Fired?

“Yep, fired.”

“My boss was a sailor,” explains Clinton, “and thought himself an expert. He was the comptroller of Grumman but actually acted more as the treasurer. We got along OK for a couple of years, but what set him off was a new concept we had. Tom Potter had an idea for a full-powered auxiliary. This comptroller said we needed to sell five of them before we could go with it. We discussed this for an hour at a board meeting. At the end of the discussion, they took a vote, and I won. I knew that sealed my fate. The boat turned out to be the Countess 44, which was quite successful.

“I really hated working for a big company,” Clinton goes on. “I had already made plans to do something else. I was ready to resign anyway. If they had just waited a few more weeks, I would have left on my own, and everyone would have been happy.”

Clinton bought out a troubled sailboat-maker called Sailstar in West Warwick, R.I. “I still had the lease on the Bristol factory, and moved the company there,” he says. “Carl Alberg designed a 27-footer for me. I called it the Bristol 27, and soon the Sailstar name faded away.” He changed the company’s name to Bristol Yachts, and thus was born another famous sailboat manufacturer with a Pearson pedigree.

Back in Portsmouth, business was booming for Pearson Yachts, but not everything the company was building would float. Grumman combined the sailboat company with its subsidiary that made aluminum canoes and truck bodies. “Grumman was building aluminum trucks for United Parcel Service,” states Everett. “Soon Pearson Yachts was making the fiberglass rooftops and fronts for the trucks. We did it really just to accommodate Grumman.”

Tom Potter was the next to leave. “I hated working for Grumman,” he says, “and I quit. I actually was out of work for a while when Clint asked me to join him at Bristol. He was building stock boats, and I wanted to do custom work.” Tom stayed with Bristol Yachts until he retired in 1972. He then went back to school to become a naval architect and began a second career designing boats. Today at the age of 84, he’s still designing sailboats.

Special Permission

Special Permission

By 1966, Everett Pearson also was ready to leave. According to Everett, “We were run by a board of directors. We had to write quarterly reports and go to board meetings. I didn’t like it at all. My interests were in producing sailboats. I decided to go out on my own. I agreed not to compete with the company for three years, so I decided to go into the industrial business.

“But first,” continues Everett, “I helped out with a 58-footer for a fellow I knew named Neil Tillotson. I had to get special permission from Grumman to do the boat, which was granted since it didn’t compete with anything Pearson was building.” Later, he teamed up with Tillotson to form Tillotson-Pearson, Inc., which has become a major force in industrial uses of fiberglass-reinforced plastics and other, more exotic composites. Known today as TPI Composites, its varied product line includes windmill blades, flag poles, aquatic therapy pools, and J-Boats, among other sailboats and power boats. Everett, 65, now serves as chairman of the board of TPI. Just 10 short years after it all began in Clinton’s garage, no one named Pearson was running Pearson Yachts.

“Shortly after [Everett left], Grumman asked me to run the company,” says Bill Shaw. “Never having done that, I said sure.” Bill was made the general manager of the Pearson Yacht Division.

“We put together a great team,” he continues. “And Grumman was great to work for. They were very supportive in getting us the best equipment and machinery. We had computers to help us cut out materials. They also expanded the Portsmouth facility later on so that we could build bigger boats.”

According to Bill, Grumman also started making firetrucks and motor homes based on a truck body. “It’s interesting to build boats on one side of a plant, and motor homes on the other. I had to be a diplomat. At one point, we even built some modular housing for Grumman. We erected it at the plant and used it as an office as a prototype.” Grumman began manufacturing

the housing at another site and continued making aluminum canoes in New York.

Under Bill Shaw’s leadership, Pearson Yachts enjoyed rapid growth in sales in the late ’60s and early ’70s. The product line was varied and included powerboats as well. Sizes ranged up to 44 feet, thanks to the new production facility Grumman funded. Then the fuel crisis hit in the early ’70s, and the company found itself at a crossroads of sorts.

“When the fuel problems hit,” says Bill, “the powerboat business was hurt badly. We found that people went to sailboats who never thought they’d set foot in one previously. We decided we were a sailboat company and wanted to concentrate on that. We also came face-to-face with the realization that to be successful in that line of business, we had to be committed to the dealers. Other manufacturers were always after our dealers, too, trying to steal them away from us.”

Bill started holding meetings with an advisory board partially composed of dealers. “The boats were developed with specific price points in mind and with dealer input,” he continues. “A new design had to satisfy a lot of people; otherwise it wasn’t worth the trip. More than once we had what we thought was a great idea, but the dealers would turn it down. We would pull them into the plant and bounce ideas off them. They were extremely helpful to the success of the company.”

Condo Boat

John Burgreen, who now owns Annapolis Yacht Sales in Annapolis, Md., one of the earliest Pearson Yacht dealers, was one of those dealers Bill counted on. “Pearson would get a group of us together from different parts of the country,” explains John, “to brainstorm new ideas. We talked about what should go in a particular boat, what the market was demanding. We’d discuss such things as heads that had to be bigger, or we had to have stall showers, or we needed more performance-oriented boats, or more cruising boats. All the dealers worked together pretty well.

“One boat that comes to mind,” muses John, “is the Pearson 37. We called it the condo boat. We had more fun than you can imagine working on that boat. We went berserk. Everyone there was at fault for that one, although it did pretty well.”

The 37 was introduced in 1988 to considerable dock chatter. At the Annapolis Boat Show, people could be heard saying, “You’ve got to see the Pearson 37!” The boat had a queen-sized island berth forward, two swivel chairs in the saloon, a television and stereo center, and a separate shower stall. The cabin was about the most luxurious to be found in a production sailboat. It made a definite statement about how serious Pearson was at attracting new customers in a changing market.

Another key factor in the company’s success was its advertising firm, Potter-Hazelhurst. “Their strength was marketing, not necessarily in printing pretty ads,” Bill says. “One of their employees developed an index of buying power by county and city for the whole country.” The company used the data to develop sales estimates for particular markets, a most effective tool. “It worked well for the dealers, giving them sales goals, and a good idea of what their sales should be,” he adds.

According to Tom Hazelhurst, his firm handled Pearson’s marketing and advertising efforts from 1969 until the end in 1991. “Pearson grew during that period, and so did we,” he says. “Under Bill’s tutelage, they built damn good boats. I’m not saying that because I was their advertising man, but because I bought two of their boats. The boats just don’t break.”

In 1980, Grumman expanded the Portsmouth plant to 240,000 square feet to build even larger sailboats. The Pearson 530 was the largest boat the company ever built. The firm also began building powerboats again, although none was designed by Bill.

By the mid-’80s, Grumman started looking for a buyer for Pearson Yachts. “I tried to buy the company in 1985,” says Clinton, “when Grumman made it known they wanted to sell. But the deal didn’t come off. Times were already starting to change in the sailboat business. Pearson only lasted as long as it did because of the kindness of Grumman. I doubt the company ever made any money for Grumman.”

Bill Shaw disagrees. “We certainly had some lean years, but we also had some very productive ones,” he states. “Sure, Grumman looked at it as a business, and we turned a good profit for Grumman in the healthy years, especially when we started building the larger boats with larger profit margins. I don’t think they would have kept the company that long if we weren’t doing well for them.”

Business Downturn

Business Downturn

In March 1986, Grumman sold Pearson Yachts to a private investor group headed by Gordon Clayton.

“Gordon had no prior experience in the boating business,” says Bill. “When he came on board, we looked forward to taking advantage of his overall business experience to add a healthy element to the company. It’s unfortunate that when he came along, business started going badly for the entire industry.”

The company was also faced with an aging model line. “Things like aft staterooms and open transoms were popular, and we couldn’t add those features to many of our boats,” Bill explains. “We worked with the models we could adapt. For example, we brought back the 34, and we also changed the Pearson 36, which we extended and called the 38.”

In 1987, Pearson introduced several new designs with wing keels and 10-year warranties against hull blisters. “I’m partial to centerboarders myself,” adds Bill, “but not everyone is. The wing keel was a good way to get shoal draft.”

Gordon Clayton was “aggressive in picking up Sunfish and Laser for us,” says Bill, “and also O’Day. That gave us entrée to a segment of the market we had missed before.” O’Day also had acquired the Cal name earlier, so Pearson had a number of well-known names for marketing purposes.

But a general drop in business was well under way. The money chase that began in 1956 for Pearson was getting tougher.

Bill Shaw says of the demise of the company: “It was a number of things, not the least of which was a rapid fall-off in sales volume. When we thought about it, the most serious competition we had going against us was our old boats. Also, sailing was getting so expensive, and that created a loss in interest [by the public.] When the Ensign first came out, it sold for $4,000 to $5,000. At the end, it sold for $14,000, and not one screw was different. The Ensign association wouldn’t let us change anything.

Add to that the rising costs of slips and insurance, and owning a sailboat was simply too expensive for many people.

“We needed volume to make a go of it,” continues Bill, “and without that, we had to increase prices. We couldn’t just cut out the unneeded overhead. We had that huge 240,000-square-foot plant for one thing.”

By 1990, the boating industry was rocked to its roots by an economic recession, and by a 10-percent federal luxury tax on such items as new boats costing over $100,000. While Bill maintains the luxury tax had little impact on Pearson, because few of its sailboats cost over $100,000, the buying public was confused about what the tax did and did not apply to. For example, the tax did not apply to brokerage boats – but sales of those fell, too. Many wealthy clients simply stopped buying boats altogether, refusing to pay the luxury tax on general principle even though they could easily afford it.

The end result was disastrous for many boat manufacturers. The drastic drop in sales forced Pearson into bankruptcy court in 1991, with Bill retiring just before the end. “I miss the business tremendously,” he states. Bill, now 73, has had some health problems, but “with medical science these days, they keep me going,” he says.

Record Production Run

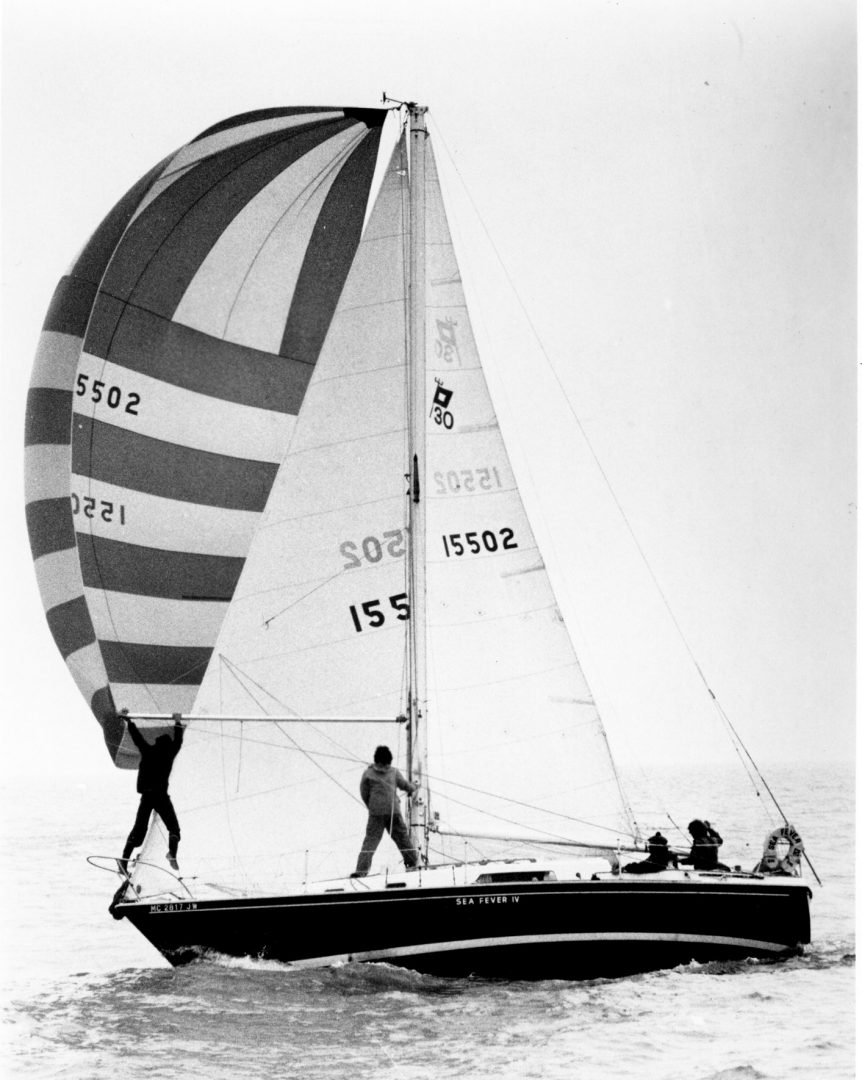

When asked to name his favorite from the many designs he did for Pearson through the years, Bill laughs, saying, “I get that question a lot. When I was active in the company, my answer always was ‘the next one.’ In its day, the Pearson 30 (pictured on Page 19) was quite successful, especially with racing in mind. I’m helping my son do some alterations to his 1972 P-30. I also am very partial to the 365 as a cruising boat. It was so popular we had two production lines for it. It’s a good, wholesome cruising boat. The Pearson 35 was one of our most successful. It was in production for 14 years, which was quite a record. We never approached that again. Most designs would last five years or so.

“I get several calls a week from boat owners, asking for help,” he continues. “When the company went on the blocks [with the turmoil of many ownership changes] we lost control of so much. Everything was documented so well, and that’s all gone now. When I get calls now from owners about their boats, I can’t answer them unless I can remember, and that is getting to be more of a problem,” he chuckles. “It was a wonderful 27 years for me.”

Shortly after the bankruptcy, the Pearson molds and trademarks were sold to Aqua Buoy Corporation. To make the situation even worse, Aqua Buoy went bankrupt before taking possession of the molds and moving them from the Portsmouth plant, which Grumman still owned. Grumman reacquired the molds in a bankruptcy sale.

This began a tumultuous time for the remnants of the Pearson name and molds. Through a series of other sales and actions, the Pearson and Cal molds and trademarks eventually were sold to a new company, formed in January 1996, called Cal-Pearson Corporation. In the disclosure statement sent to prospective stock purchasers, the principal office was listed as Bristol, R.I., but the corporate office was in Bethesda, Md. Clinton Pearson was listed as the chief executive officer and Christian Bent as the chief financial officer. The company began a campaign to raise the capital needed to build Cal 33s and 39s and Pearsons ranging from 27 to 39 feet. Bristol Yachts, then owned by Clinton’s two sons, was to build the sailboats.

The exact number of boats Cal-Pearson actually built is not known, but certainly is in single digits. The company exhibited boats at the AnnapolisSailboat Show in 1996 and 1997. By 1998, no one was answering the phone at the Bethesda office, and the company disappeared in a cloud of lingering debt. A big part of its demise was the bankruptcy of Bristol Yachts, which left Cal-Pearson with no manufacturing partner. According to one insider, Cal-Pearson essentially ceased to exist when Bristol Yachts was forced into bankruptcy and its assets were sold at auction.

According to Clinton, “The Bethesda group offered me some stock to help them start the company. They were looking to publish the fact that I was involved to stimulate interest in others. They found it harder to raise money than they had thought. They did raise money in New York, but the overhead was so high with lawyers and accountants. It was a good idea, but only if they could have gotten proper financing. Training a new crew is so hard. It just takes quite a bit of money to get something like this started. Quite a few dealers were enthusiastic about the name returning to the market, too.”

Clinton, who is now 70, is “not currently active in the boat business, and I have no intentions of getting back into it,” he says.

Different World Today

Says Everett of the Cal-Pearson Corporation, “So many people jump into the boat business without knowing what it takes. They were trying to market 10-year-old designs, and that is tough to do in today’s climate. People knew they were old designs because their competitors were constantly pointing it out to the public. And trying to start the Cal line at the same time was too much.”

Bill Shaw has a similar take on the short life of Cal-Pearson. “People absolutely lose their smarts when they get around boats,” he says. “It’s a different world out there today. Unless you have a big bankroll, you can’t make it. To develop a new 35-footer, with molds and tooling, would take several hundred thousand dollars. If you are looking at a line of eight to 10 boats, as they were, it just doesn’t make sense.”

But the venerable Pearson Yachts name refuses to die. At the National Pearson Yacht Owners’ Association rendezvous in Bristol, R.I. in August, Everett Pearson announced to the group that his company, TPI, had just purchased the trademarked name of Pearson Yachts.

Says Everett, “I wanted to grab the name while I had the chance. We didn’t buy the molds. All that stuff is too old.”

He continues, “We do plan to develop new models. I bought the name so we’d have it there. But we have some projects involving buses, people movers, and a couple of other things that I need to get moving before we start [on a new Pearson product line]. We have some guys working on it, studying the market. Up here in New England, we’re more efficient at building large boats, rather than competing with small-boat manufacturers. So we probably will start with something over 35 feet, maybe in the 40- to 42-foot range.” It probably will be at least one to two years before any new Pearson yachts hit the market.”

When asked the purchase price of the trademarked name, Everett replies, “I haven’t told anybody. I paid too much. But when you’re buying your own name back, you get carried away.” He was determined to make the purchase. “It took me three months of phone calls to track these people down,” he says.

TPI will handle the marketing itself, as it has done for several of its other boat lines. Everett foresees a network of six to eight dealers. “That’s all we’d want. We need to give them enough territory so that they don’t compete with each other.”

With some 20,000 boats out there bearing the Pearson name, from eight-foot dinghies to 53-foot sailboats, the Pearson legacy is already well-established in the history of boating. Very active owners’ groups keep interest in the boats quite high. In some areas, certain Pearson models sell by word-of-mouth without even being advertised. The Pearson name also is one of the most active on the Internet. Pearson bulletin boards abound on the net, and usually are among the most active in the online sailing community.

Certainly, Pearson owners can take solace from knowing that for the first time in over 30 years, someone named Pearson once again is in charge of Pearson Yachts. The symmetry of events is satisfying for a company that has endured so much turmoil in the last decade. Pearson Yachts sails on.

Article first appeared in Good Old Boat magazine Volume 2, Number 6, November/December 1999.