A near-dismasting on a Pacific passage calls for teamwork and trust.

Issue 139: July/Aug 2021

It’s 0800 and I am snug in my bunk, still half asleep, contemplating greeting the day aboard Galapagos, our 1975 Olympic Adventure 47. The motion of the boat is familiar, charging under sail toward our Cape Flattery, Washington, destination. We’re only 500 miles out, nearing the end of this long Pacific passage home from Hawaii. Then, my reverie is shattered by what sounds like the firing of a cannon upon our sturdy ship.

I jam my feet into sea boots, each on the wrong foot, while shouting to my husband, Michael, whom I hope is safe topsides. “I’m coming up! I’m coming! What happened?” I throw on my inflatable harness as I fly to the companionway. Michael is already in the cockpit and gearing up. His face is a shade of grey I haven’t seen since we got water in our 20-hour-old Beta Marine engine back in 2014.

I jam my feet into sea boots, each on the wrong foot, while shouting to my husband, Michael, whom I hope is safe topsides. “I’m coming up! I’m coming! What happened?” I throw on my inflatable harness as I fly to the companionway. Michael is already in the cockpit and gearing up. His face is a shade of grey I haven’t seen since we got water in our 20-hour-old Beta Marine engine back in 2014.

“That was our backstay. We lost it. The insulator…”

He doesn’t have to finish; I see miles of thick wire rope snaking around the aft deck. Shitshitshit! I look forward and up and see the parted piece hanging, only two feet long, swinging from the top of the mainmast. I’m grateful to see that the mizzen is unaffected; no triatic stay connects the two. Still. We. Are. Screwed.

“I have to get this sail down!” Michael calls as he leaps to the deck. The wind is on the beam and I realize we’re lucky to still have our nighttime triple reef in the main. He’s at the mast pulpit in two giant strides, uncleating the main halyard.

I am already rolling in the genoa. “I’ve got this one!” I shout as I see the main fall gracelessly to the boom.

With both sails doused, I start the engine as Michael checks for lines or stays that may have gone overboard. When he gives the all-clear, I put us in gear, steer slowly downwind, and turn on the autopilot. I call this information out to him and he pauses, eyes the sea state, then nods. Whether we should be motoring downwind after losing the backstay is a question, but we consider the meter-high swells and decide that this heading takes the most pressure off the rig. Sometimes there are no great choices.

Michael calls, “Tighten the mainsheet and get the boom centered!” We’re thinking in sync as I’m already doing just that. I begin to feel a wave of confidence—the mast is still up, we’re going to be OK, I can feel it, remember to breathe.

Together in the cockpit, we discuss our next steps. Our focus is twofold: take as much pressure off the rig as possible, and secure the top part of the mast. We’re fortunate that Galapagos has a keel-stepped mast, but we realize we still need to act quickly and decisively.

“I’m going forward to get the main halyard and bring it back here.” Michael has his captain’s voice on; I’m listening and also observing his body language. “Tie a bowline in the end of this line so I can attach the halyard. I’ll tie it to the hard point on the aft deck and then tighten it on the winch at the mast.” He hands me the line and goes forward.

I tie a bowline and immediately wonder if I did it right. I’m not panicking, but I’m having trouble concentrating, and I worry that what I tied won’t hold. When Michael returns with the halyard, I hand him my knot and ask him to check it. He reties it, but he has to think it through, too. Normally, he can tie one without looking.

After attaching the halyard to the tether and securing it aft, Michael goes forward and winches the halyard taut, creating a temporary backstay. As planned, this puts an end to what Michael describes as a sickening sight, the mast bending forward and then snapping back to a hard stop as the forestay catches it. I never see it because I don’t look. I need to think and act, and to do that effectively, keeping fear at bay is critical.

I’m breathing a bit easier as Michael returns to the cockpit. I am making constant, slight adjustments to our course to keep the boat motion easy. We are fine. The boat is fine. No one is hurt. We’ve got this. Our teamwork is spot on. Breathe.

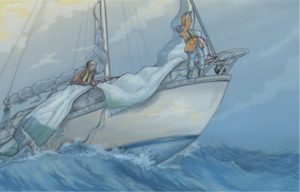

“I want to get the genoa off the furler,” Michael says. “It’s adding stress and weight to the rig. And if we do lose the rig at least we won’t lose a good sail.” This is going to be the hard part, the dangerous part. That sail is huge and heavy. Even on a dock, we have to use a lot of human power to manage it.

We decide that I will slowly unfurl the sail and simultaneously ease the halyard, while he guides the sail down to the deck. Winds are 12-15 knots, and I want to turn upwind so the sail doesn’t fill as we unfurl it and stays on deck as it comes down. But swells are still over a meter, and I don’t want Michael on the foredeck manhandling a big sail with the bow pitching. We have this crazy idea that we can do this in a controlled way. Maybe we will get lucky.

Michael begins to go forward. “Michael. Clip on.” I look him in the eye. He pauses. “I know it’s a pain, but clip on. I cannot lose you overboard to this.” He clips onto the jackline and goes forward. Deep sigh. Keep the focus on the task at hand.

I move forward to the mast holding the furling line—which is run from the cockpit winch—in one hand, so I can access the genoa halyard in the other. Michael is forward, holding onto one of the sheets so he can guide the sail onto the deck. But as I start to unfurl the sail, the wind begins to catch it, and I realize belatedly that our idea of a controlled drop at this angle to the wind just isn’t possible. I have to unfurl the whole thing—fast— to get it down, because that’s just how furlers work. I knew this. I let more sail out.

But Michael is still hanging onto the genoa sheet, and it’s already pulling him around dangerously. I stop unfurling, fearing that any more force puts him at even greater risk. In the trauma of the moment, maybe he doesn’t realize what’s happening. He had mentioned that if we lost the rig, we could still maybe save the sail; it was pretty new. Funny the things you think of under stress. I care less about the sail than losing him over the side or dropping a line into the water to foul the prop. But he’s so intent on controlling the sail that he can’t see how impossible that is. Looking back at me, his face is focused, determined, maybe a little afraid?

“Let go of the line!” I yell. As soon as he drops it, I fully unfurl the sail and let go the halyard. With the wind still partly in it, the sail still fights us; Michael has to pull it down, some of it landing in the water. Clipped onto the jackline, I scuttle forward, and together we heave it on deck. Keep your feet firmly against the toerail. Make sure of your footing. Don’t move fast. Don’t depend on the lifelines to hold you. Think things through. Keep your center of gravity low.

Sail safely on deck, no lines dragging, he hands me the head of the sail and I haul it back toward the cockpit along the side deck. It is heavy and awkward. This is when I feel the weakest, when brute strength is required. Michael rolls the sail up from the front, heaving the massive thing over and over toward the deck in front of the hard dodger. We squirrel it into a bundle the best we can, cinching it with a line to hold it down.

“Let’s take a moment,” Michael says. It’s just a few seconds, a moment to calm our brains down, acknowledge a small prayer of thanks that we and the boat are safe, gratitude for the most important things in our world.

Sails secured, temporary stay in place, we go aft to survey the damage…and realize there is none. We no longer have a backstay; otherwise everything is untouched.

We discuss our next move. The backstay that we set up is only temporary. Our mast is 62 feet tall and has—had—a split backstay. I suggest that we remove the broken stay and hardware and connect new stays—even if made of rope— to the existing chainplates, something closer to what we’d lost. Michael agrees.

Our topping lift was made from quarter-inch Dyneema spliced to a low-friction ring. We decide that he can run a line through that ring and secure it to the chainplates on each side. It’s overkill for a topping lift, but just the thing for a temporary backstay.

This plan goes through a number of iterations as we get the thing set up, using a handy billy on one side with a line that can be run to the port side winch so we can winch the whole thing tight. At first, we run the line directly through the hole in the chainplate, but it’s quickly apparent that isn’t a good idea, as the edges are sharp and will almost certainly chafe through the line.

Fortunately, Michael finds some right-sized shackles in our bag of spares. Now the line is attached to a nice, smooth, stainless steel shackle, and that shackle is attached to the chainplate. We are feeling better now, but I look at the handy billy, and I’m still worried that while the blocks themselves seem suited to this use, the only thing standing between us and another failure of this tempo¬rary rig is the small snap shackle assembly at the top of the block. It just looks too small. Maybe it’s strong enough to bear this load, but I don’t know that for sure, and it’s going to keep me up at night.

I suggest we attach a safety line that bypasses the handy billy and attaches to the chainplate shackle. It would bear part of the load. And if the top of the handy billy failed, this backup would give us time to address the problem. I am all about backups. It may be mostly psychological, but it counts when you are trying to avoid a crisis; we make the adjustment.

Now that the mast is secured and we are out of immediate danger, we stand in the cockpit and look at each other. “I’m sorry,” he says. I don’t know why he is apologizing for anything, and that’s when I begin to cry. Not big gulping sobs or out-of-control ugly crying, just kind of quietly weeping that this lovely passage has come to such an abrupt end. My dream of passing by Cape Flattery with sails flying fizzles, and I am heartbroken for us. That’s what I’m crying about, and I’m not even sure why that is important to me. My mind knows that I am having an adrenaline stress response, but my heart knows I am just sad. I hold these two pieces of reality at the same time. Truth is truth. We will need to baby the rig until we get it repaired. We will motor for days. I am bereft.

We give ourselves some time alone to be with our own thoughts and feelings before going on to the next tasks. Then, Michael begins coiling up the broken backstay and I help him tape it securely to be stowed below. I get warm clothing and a handheld radio to add to the ditch bags in the cockpit. At some point, I realize that the extra clothing in the bags is for sunny warm weather and warm water. Hats and gloves go into the bags. I put my computer in its case and put that in my bag. I double-check everything, again. Michael watches me do this. He knows me. Best to be prepared.

“I don’t know if this helps,” he says, “but even if we lost the rig, you know that the entire mast would not come down, right?”

Well, no, I didn’t know that. In my head, I had pretty catastrophic visions of the entire 62-foot stick falling forward and completely destroying the deck, the boat taking on water, Coast Guard rescue kinds of things. He explains that the mast is two sections, and that the likely scenario would be that the top may part from the bottom. So we would lose the rig and it would suck real bad and cost a lot of money, but it would be very unlikely that it would cause us to lose the boat.

“Actually, that helps a lot.” I say. “Thank you for telling me. I knew that our mast was built in two pieces and I’d forgotten. I remember now.”

Regardless, we decide it would be prudent to let the Coast Guard know our situation and set up a comms schedule with them. We email them using the Iridium Go. They reply swiftly, the start of a twice-daily check-in that improves crew morale.

Night and darkness arrive, and every little noise spells doom in Michael’s mind, concerned about whether our fixes will hold. Surprisingly better at denial than Michael, I get some shut-eye. In fact, I adopt a fairly fatalist view during situations like this and prefer to face death well rested. Besides, I am exhausted in mind, body, and spirit, and nothing can keep me from sleep.

When I come up to the cockpit in the morning, Michael is playing “dodge that ship” and is bleary-eyed. He has sent our position to the Coasties and to our friends on land, and he has downloaded the news headlines for me to have over my coffee (some rituals are sacred). I suggest he try to sleep. We have four days to go to Neah Bay, Washington. (We don’t know at the time that Neah Bay is closed due to COVID-19.)

In the end, we made it safely home. In short, it was our teamwork and a lot of luck that saved the rig. Being able to keep focused on the tasks in front of us, having years of experience handling smaller boat crises together, knowing how to talk and listen to one another in an emergency, and having faith in each other’s abilities are all time-earned skills that were put to the serious test. Not insignificant is Michael’s ability, as captain, to listen to me and to take what I have to say seriously, valuing my opinion and ability to problem-solve, sometimes doing things he doesn’t think are necessary just because I think they are. That’s called respect.

Back in our home waters of Washington State, we are a sailing boat again, gliding across the water whenever the wind blows. It feels good to look aft and see those shiny new turn-buckles and the silvery strands of a safe, new backstay.

Melissa White is a licensed therapist practicing in Washington since 1989, specializing in anxiety and its management. After sailing in Washington and British Columbia for 15 years, she and her husband, Michael, took the big leap in 2017 and sailed to Mexico, where they spent three years on their Olympic Adventure 47, Galapagos. Since then, they have sailed to Hawaii and are refitting the boat for another long-distance trip. Read more at LittleCunningPlan.com

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com