Four friends and a refit rocket tackle the raucous Race to Alaska.

Issue 136: Jan/Feb 2021

Gripping the tiller in my left hand and the coaming in my right, I spin my head from side to side, desperate for my eyes to connect with something in the inky black night. My watchmate, Mark, and I are both confused. Aboard a Santa Cruz 27 in the Johnstone Strait—a narrow, 68-mile channel that is part of the Inside Passage that connects southeast Alaska and northwest Washington—the water around us is being whipped into a frenzy and we don’t know why. There’s not a breath of wind. Then it hits me. “Wind is coming. Lots of it.”

Sure enough, seconds later Wild Card is pressed hard over to starboard. The anemometer briefly reads 40 knots, and our crew is suddenly all action. We’re overcanvased, having spent the past several hours trying to squeeze every fraction of a knot we could from zephyrs. Now, the wind keeps coming and Mark and I only manage to ease sheets before the off-watch crew, Mike and Robbie, appear on deck half-dressed to help calm the melee.

With the #1 soon wrestled and lashed to the foredeck and two reefs tied in the main, we shoot onward through the strait, forereaching through the night. Mike relieves me from the helm, and I drop down below into the small cabin, strip off my wet foulies, and climb into my cozy pipe berth on the port side.

I listen to the howl of the wind and I feel the hull undulate. I stare at the fiberglass overhead just inches from my nose. “The Race to Alaska is no freaking joke,” I say to myself, chuckling. We were then in second place among a fleet that had whittled already from 39 to 30, and I marvel at the near miracle it is that we even got the old Santa Cruz warhorse to the start line at all.

The Race

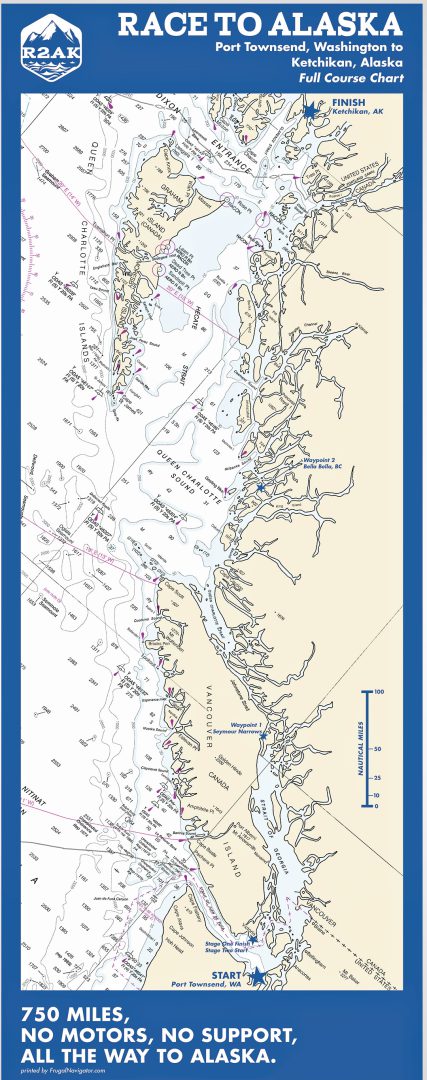

Race to Alaska (R2AK) is an annual, 750-mile, human- and wind-powered suffer-fest that starts in Port Townsend, Washington. The first leg is 40 miles to Victoria, British Columbia, where racers make a quick stop to clear into Canada. Then, from Victoria it’s a long, nonstop passage to the finish line in Ketchikan, Alaska—a lot harder and more complex than it sounds.

The rules are intentionally simple: No engines, no outside support, no classes, no handicaps. Racers pass through two Canadian checkpoints, one at Campbell River and one at Bella Bella (the latter was the only checkpoint in the 2020 race), but otherwise, the route is your own. The Northwest Maritime Center of Port Townsend, Washington, runs R2AK and describes the challenge this way: “It’s like the Iditarod, on a boat, with a chance of drowning, being run down by a freighter, or eaten by a grizzly bear. There are squalls, killer whales, tidal currents that run upwards of 20 miles an hour, and some of the most beautiful scenery on earth.”

It’s also been called “the America’s Cup for dirtbags,” in the fondest, most irreverent sense of that illustrious term.

Oh, and the winner of R2AK walks away in soggy sea boots with a cool 10 grand in cash nailed to a log. The second-place crew settles for a set of steak knives (they’re actually beautiful pieces of cutlery). Everyone else gets the chance to say they finished…or didn’t. Many don’t. Of the 39 teams that registered for R2AK in 2018, the year we raced, only 21 crossed the finish line.

I was captivated by the race when it first ran in 2015. After watching the first three races from the sidelines, I couldn’t take it anymore. I wanted in, I needed in. But I didn’t want to race with just anybody on any old boat. I wanted to accomplish this magnificent crazy feat with friends.

Soon after I texted my good pals Mark Aberle and Mike Descheemaeker, I heard back: “We’re in!” Led by Mark, we added a fourth compadre, Robbie Robinson. Team Wild Card was thus born of four buddies who had met years prior, living aboard on the same dock in Seattle. It was perfect. Now, we needed a boat.

The Rocket

Our list of requirements was short. The boat needed a cabin big enough to get four grown men out of the elements, it needed to be seaworthy enough to handle the rigorous winds and currents of the notoriously rugged Inside Passage, it needed to be fast, and it needed to be affordable. Our criteria eliminated the rowboats, multihulls, kayaks, and stand-up paddleboards that some racers chose and narrowed our focus to an older, sporty monohull sailboat.

We scoured Craigslist. Luckily, we found the proverbial diamond in the rough in a 1978 Santa Cruz 27, hull number 55. SC27s were considered rockets ahead of their time in the late 1970s, but time had not been kind to hull 55. We found her with soft spots all over her balsa-cored decks, bent spreaders, a bent spinnaker pole, and really old sails. We only found the wasps’ nests down below later. Essentially, we bought a nice double-axle trailer with several months’ worth of boat projects perched atop it.

So it happened that on a sunny July day, while most of the 2017 R2AK fleet was still navigating the Inside Passage, Mark trailered our boat from cow pastureland in central Oregon to Skykomish, Washington (population 198), where it went into Mike’s barn-turned-SC27-spa.

Over the ensuing months, Mike, Mark, and Robbie replaced about 90 percent of the decks and cabintop. Our stalwart crew attacked nearly every other part of the boat as well, replacing wiring, winches, and electronics. They even fitted a trapeze to the mast and ordered a fresh set of Ballard Sails including a main, #1, #3, and a big, black asymmetrical spinnaker. An asym on a SC27 you might ask? Yes! They installed a carbon Forespar bowsprit to fly it from, and the sail turned out to be a speed-inducing adrenaline pumper throughout the race. Our boat got new spreaders, standing rigging, and running rigging.

During this time, I felt a bit like a slacker, but commuting from Seward, Alaska, wasn’t an option. (To this day, I cannot give Mark, Mike, and Robbie enough credit for the work they put in.) Instead, I focused on my role, one that would really start on race day: tactician. From Seward, I studied the course and thought through all the right decisions I’d need to make to keep the boat moving as fast as possible, every minute of every day we were on the course.

The major piece of the puzzle we had to figure out was how we’d propel our SC27 through the water when there was no wind. And there would definitely be periods of no wind. In this race, sitting and waiting for wind, maybe even losing ground to a contrary current while waiting, is a recipe for losing. But we lucked out.

Mark had beers with a previous R2AK competitor who agreed to sell our team the pedal drive his team had used. Conveniently, it wasn’t too difficult to mount our new drive to our boat’s outboard motor bracket. When we finally tested our human-powered propulsion solution, we were pleased to see that it could drive Wild Card forward at a respectable 2 knots—2.5 knots if the pedaler’s legs were feeling fresh.

From the beginning, there seemed to be plenty of time to get things done…and then, all of a sudden there wasn’t. With the race start looming on June 14, we found ourselves in a race to finish before the race.

The headlong rush into R2AK madness ended with a downhill tow to Seattle for paint and bottom fairing and a team rendezvous in Port Townsend; and the race was on.

The Ride

When I re-emerged sleepily on deck after the melee in the night, Johnstone Strait had utterly changed. Gone were the washing-machine seas and gale-force gusts. In their stead was a flat-gray waterscape that blended into the fog hanging in the air and clinging to the surrounding mountains.

We were ghosting along under full sail, and I was happy to learn that we’d slipped into first place overnight. The Olson 30 Lagopus was now in second, and the Melges 32 Sail Like a Girl was in third.

If you’d told me before the race that we would be in the lead days into it, I would have thought you were crazy. I knew our team of quality sailors was up to the challenge, but it would have been hard to imagine a Santa Cruz 27 pulling ahead of so many other boats in the field that are theoretically faster. My hope at the start was that we’d finish the race, maybe somewhere in the top 10 or 15.

Now my racer brain was in hyperdrive to squeeze everything we possibly could out of this boat to stay in front. For a while, I was successful. After exiting Johnstone Strait, we sailed fast up Queen Charlotte Sound, endured a weird night at sea off the notoriously brutal Cape Caution, and we still held onto our lead.

Arriving at the checkpoint at Bella Bella, we converged with the Olson and the Melges, and they both squeaked ahead of us, much to my disappointment. From there our only hope was to throw a Hail Mary by going where the other boats didn’t, maybe gaining a lucky break in wind or current that would give us an advantage.

It was our only option, but a gutsy call nonetheless. Onward we went out into Hecate Strait while the two frontrunners went up the inside. Out in the open, we promptly sailed into a massive windless hole. And when I say windless, I mean nothing. Zero. A forecasted 10- to 20-knot northwesterly breeze was a bust. We took turns on the pedals in an effort to keep the boat moving, but we weren’t encouraged because we knew that Lagopus and Sail Like a Girl could both go faster than we could under human power alone. We desperately needed a wind advantage.

Finally—finally—the tardy northerly did show up and we used every bit of it to make massive strides on the leaders as we crossed the Canada-Alaska border. It was a huge high…and it was followed by a big low. We could see both boats ahead of us when the wind shut off again. Then we watched as they slowly got smaller. My log entry from that moment read:

“Alas, as we sit in the doldrums again, it seems to be too little, too late. We’re 80 miles from Ketchikan and are pedaling. It’s all we can do. Fortunately, spirits amongst the boys are high. Did we ever imagine being in this position? Hell no. But we’ll take it. We’re having the time of our lives!”

After pedaling hard through the windless night, we entered the last straightaway to the finish. At this point, the wind rewarded us with one final run. Up it came from behind us, first 5 knots, then 10. We hoisted our big, black asymmetrical for one last joyous run and positively shot towards downtown Ketchikan. The wind rose to 15 knots, then 20 and Wild Card was up on plane like a surfboard, hitting 12 and 13 knots of boat speed. At the helm, I was all smiles. All of us hooted and hollered with adrenaline-pumping fun.

We threw in one last wipeout of a jibe for good measure, then picked our way into Ketchikan past cruise ships moored in the pouring rain. When we jumped onto the dock to a waiting crowd, beers were pushed into our palms and a bell rang out to signal that we had done it. We had finished the Race to Alaska.

The Results

In the end, Sail Like a Girl held off a very persistent Lagopus to claim the $10,000 prize and 2018 R2AK bragging rights. Lagopus got the steak knives. A six-day, 22-hour run earned Wild Card third place. It was one hell of a ride.

Since then, I’ve replayed almost every mile of the race over and over in my mind. The holes of no wind. The breeze when it did come. The heat. The cold. The fog, and the purest cobalt sky. The many tacks and jibes. The downright wicked currents. The pedaling. The sailing. The friends. Snagging first place in Johnstone Strait and holding it for nearly two days. Finishing in Ketchikan after absolutely sending it in 20-plus knots of breeze. Now that was some exhilarating sailing.

Never in my wildest dreams did I think our team would take a dilapidated 1978 Santa Cruz 27 purchased from Craigslist and pulled from a field in Oregon, and then go out and compete at the top of the R2AK fleet. We had sailed our boat as a team just once before the race and still went toe-to-toe with a Melges 32 and an Olson 30. We held off the many trimarans in the field! We gave it our best, leaving nothing out there.

And truth is, that’s the only way we could have done it. At its core, it’s a crazy idea, that so many racers in all manner of small craft—everything from open dinghies and hot trimarans to kayaks and paddleboards—can try to navigate, as fast as possible and without an engine, this intimidating distance and these challenging waters. And that, more than anything, is what makes it a boat race like no other. It taps into the raw and raucous spirit of everyone who enters, and everyone who gets it and vicariously follows along. Literally and figuratively, it’s a boat race into the wild, and an adventure I’ll never forget.

Andy Cross is exploring the western Pacific coastline, from Alaska to Panama, with his family aboard Yahtzee, their 1984 Grand Soleil 39. He is the editor of 48˚ North magazine and former managing editor at Blue Water Sailing magazine.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com