A quick dismasting led to months of navigating insurance claim waters.

Issue 136: Jan/Feb 2021

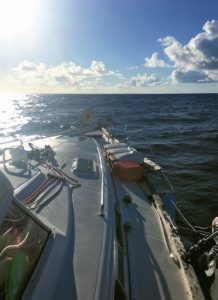

Five seconds is all it takes. Five seconds for your entire rig to come down, causing tens of thousands of dollars of damage. Our five seconds came last season on an overnight passage in the Caribbean, just after sunrise, 30 miles from our destination. Five seconds can ruin your whole day.

My husband, Aaron, and I immediately checked for hull damage. Finding nothing, we cut away the entire rig. It was eerie watching our sails billow underwater and finally sink. We fired up the engine and motored the rest of the way in shock.

crashing down for what was, at the time, no apparent reason.

The dismasting of our 2001 Bavaria 42 CC was the result of a failure of the belowdecks tie rod that transmitted loads to a port-side chainplate that supported an upper and lower shroud. We later learned that metal fatigue caused the failure. According to multiple surveyors, the large stainless steel rod likely had a manufac¬turing defect. It failed from the inside out, over a 10-year period. We learned that there was no way (absent disassembly and careful examination) that a visual inspection, even by a professional rigger, would have revealed the damage.

When it failed, winds were comfortable and steady, the sea was calm. It was just time. And in five seconds, the rod burst through the deck and sent the whole rig into the water.

The event was traumatic, but it was the months that followed, resolving a massive marine insurance claim, that truly tested us. We learned a lot during those months as we navigated the claim process with our insurance company. Following are 11 things I want to share, in the hope that they help others.

Stick to the facts.

Don’t assume blame or fault. When you make the initial contact with your provider, keep it brief: state what happened, state any important facts you feel are needed (in our initial document, we stated that we had replaced our rigging a year prior), and otherwise let the process play out.

Put your best foot forward.

Our insurance company quickly scheduled an adjuster to come to the boat and assess the cause of the event. Before the adjuster came, we did our best to clean up Clarity while leaving all damage from the dismasting as it stood. Perhaps our efforts did not matter, or maybe they made a huge difference. Our thinking was that, knowing that the adjuster had our fate in his hands, we wanted him to step aboard the boat and have the immediate impression that this was our family home, and we cared for it and maintained it as such.

At the same time, we provided a concise and factual “Owner Incident Report” that included a description of what happened (based on our observations, not guessing at root causes) and the steps we took to mitigate further damage and maintain the safety of our crew. Beginning with this report, we took a very professional approach to the documentation we submitted throughout the process. We believe this was instrumental in receiving our claim as soon as possible (which is not the same as soon).

We never assumed our insurance company knew anything that we did not tell them. Part of being professional meant responding quickly to any questions from our adjuster—we knew that we were likely not the only claim on their desk. For the same reasons, we maintained a good relationship with our insurance investigator/adjuster. We imagined the grumpiness they face every day and resolved to be the pleasant faces that stood out; it couldn’t hurt.

Patience is a necessity.

Settle in for the long haul. It took us nearly three months to even learn that we would be covered. The claim was fully closed seven months after the dismasting. Though this felt like forever, we know that our insurance company actually worked quickly.

Get approval for any necessary emergency repairs.

There will likely be some repairs that cannot wait for the lengthy claim process. We had a hole in our deck that needed to be immediately patched, unless we wanted an indoor monsoon every time it rained. We explained to our adjuster that we needed an emergency patch to prevent additional damage, and it was approved, with the idea that a full repair would be done further down the line.

Getting work estimates is your responsibility.

Other insurance providers may handle things differently, but we learned quickly that we were responsible for finding contractors to quote every aspect of our repairs so the insurance company could review them. As you can imagine, these things happened on Caribbean island time; for us this meant another healthy dose of patience.

Prepare for a full-time job.

We thought that the insurance company would be more involved in hiring contractors and getting the boat fixed, but they are really just the money men. Once they approved the costs we submitted, it was our job to hire contractors—scheduling them, overseeing them, and paying them.

Hire a surveyor, and maybe project manager too.

We did not hire a surveyor until three-fourths of the way through the repairs, and this was a mistake. We hired someone independent who, acting on our behalf, checked and documented the work. We submitted the cost of our surveyor to our insurance company and they covered it.

We also hired a local, reputable professional as our project manager, who served as the liaison between us and the contractors. Once we took this step, everything was much smoother. We submitted the cost of our project manager to our insurance company as part of the claim, but they declined to pay. We paid for this out-of-pocket and it proved worth every penny. That said, we were mindful that nobody would care as much about the project as we would, so we stayed involved. We were on-site regularly, but we weren’t pests. Owners can make a mess of things by trying to be involved in every decision.

Keep the claim open.

We wanted closure, but we kept the claim open for months after all the work was done. We knew that once we closed the claim, we would not be able to reopen it, meaning we would not be able to receive additional funds to cover any unforeseen problems weeks or months later.

An example of how this came into play for us was the “No Cash, No Splash” hold contractors placed on our boat. We had to pay bills in full before the new rig could be tested with a proper sea trial. Knowing the claim was still open gave us some peace of mind in case something went wrong during the sea trial and the repair wasn’t right.

Understand the money.

We asked how and when we would receive funding from the insurance company, and how and when the contractors we hired expected to be paid. This was critical.

Many contractors require a deposit on larger jobs before they will start work. In our case, we needed to get the order in to the factory for our mast, and we had to pay half before they would even put us on their build schedule. This meant that before work could begin on Clarity, we had to pony up about $25,000. To keep from having to float this expenditure, we worked with our insurance company to approve and make partial payments before the full claim was even approved. In the end, we were paid in four separate disbursements over the seven months.

Another wrinkle exists for those who have a mortgage on their boat. In those cases, some banks may require that they receive payments from the insurance company before forwarding that money to you, which can cause major delays. If you’re in this position, ask your bank to allow your insurer to pay you directly. The best argument for this approach is preventing delays to the repair schedule, which can result in higher expenses. Regardless of how you’re paid, if you’re out of your home country, plan time for international wire transfers.

For some of the time that our boat was being repaired, we were in the States and our boat was in the Caribbean. During that time, it wasn’t possible to pay cash (and some of the bills were too big to allow for cash payments). In those cases, we had to pay contractors using international wire transfers, and we requested our insurer pay for the cost of those wires. It’s all part of the dance.

Prepare for unforeseen costs.

While our insurance company covered 100 percent of the repair costs after our dismasting, the time it took to complete repairs meant that our boat got stuck in a hurricane zone during hurricane season. Accordingly, we had to pay significantly higher insurance premiums to remain insured in our location during hurricane season. We appealed this expense to our insurer, but they declined our appeal. Additionally, Clarity is our family’s home, and because we were not allowed to live aboard in the yard where our work was done, we were forced to find (and pay for) housing. We asked the insurance company to cover these costs only to learn they are not covered.

Extend grace.

Extend grace to each other— your spouse, your kids, and yourself. This ordeal was trau-matic, and there was fallout. All three of us experienced a form of PTSD, at different times and when we least expected it. This could have broken us (some days, we were certain that it had), but in our vulnerability we were able to find common ground and commit to seeing this through, however it played out. I think we came out the other side stronger.

The Takeaway

It was shocking when our rig came down without warning, but in the hours that followed, we did just about everything right. We quickly and calmly checked for hull damage and we had the tools aboard to cut the rig away, before it could do more damage. We got ourselves to port and began the long, trying process of making Clarity whole again.

As I related in the story, we kept our dealings with the insurance company concise, prompt, and professional; I think this approach went a long way toward achieving successful results. We showed patience and compassion to one another. But I think things would have moved a bit faster and more smoothly had we hired a surveyor and project manager sooner than we did.

Our biggest lesson learned from this experience has to do with decisions we made a year before the dismasting. At that time, we hauled and had the rig inspected. When a damaged shroud was pointed out, we didn’t hesitate to replace all of our standing rigging—above deck. What we didn’t do is replace anything with threads, including bolts and tie rods that are a part of the rig. We did not disassemble our tie rod and chainplate hardware and have it fully inspected (no one at the time advised us to do this). This is very different from inspecting it in place. And we believe the results would have been different.

Installed, our tie-rod system looked perfect; it was shiny, with no pitting or rusting. But the metal was rotting from the inside out, especially under the nuts of the tie-rod assembly.

There was no way that a rigger inspecting the pieces in place down below would have seen it. However, had those pieces actually been disassembled, likely there would have been visual signs of deterioration on the threads under those nuts, found using a magnifying glass or dye testing.

The riggers with whom we consulted during the dismasting repairs said they require all of their customers who request a rigging inspection to either disassemble every part of their standing rigging—including tie rods and chainplates—for inspection or sign a waiver.

In short, replacing only our wire standing rigging was a mistake and gave us a false sense of security. Like a chain, a rig is only as strong as its weakest supporting link.

Additional Insurance Tips

When we were shopping for a boat insurance policy, we secured quotes from a handful of major providers. We compared every line and pulled the trigger on a plan that was more robust than others, including something very important: consequential damage. This language insured us not just for what is determined by a surveyor to be the actual cause of the damage, but everything that is damaged as a result of that cause. In our case, the port-side tie rod failed. Everything else—the standing rigging, the mast, the fiberglass, the wood-work, the metalwork—was consequential damage. Even if it had been determined that we were at fault for the tie-rod failure (which we were not), the damage that failure caused would still have been covered. It’s a very powerful provision. We will never again sign on for a policy that does not include consequential damage. Note that it may not be called “consequential damage” in all policies, so read carefully and ask your broker.

Track and log all of the work you do or have done on your boat. Keep all receipts. Save all emails. If possible, document them with photos that are time stamped. I’m not talking about claim-related work, but all work, for all the time you own your insured vessel. This record keeping is your solid proof that you are doing due diligence as an owner to address the normal wear and tear on your boat and to fix what needs fixing. We had these records, and they proved critical in getting our claim reimbursed. We had our rigging fully inspected, and our standing rigging fully replaced, just a year before the dismasting. Thanks to Aaron’s methodical cataloging of all of our important boat papers and pictures, we were able to prove immediately to our insurance company that we were not neglectful owners.

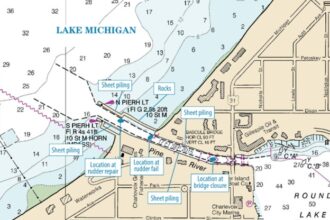

Megan Downey is a full-time cruiser who has been living aboard her 2001 Bavaria 42 CC with her husband, Aaron, and 8-year-old daughter in the Caribbean for the past four years. Prior to that, they owned a Pearson 36-2 that they cruised in the Great Lakes, with Chicago as their home port. They have been sharing their adventures – the good, the bad, and the ugly – since casting lines. Read more about them at sailingclarity.wordpress.com.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com