A Sleek Racer/Cruiser From the Mid-’80s

Issue 155: March/April 2024

Jan Bednarski was introduced to the world of water sports by his father near the prairie city of Edmonton, Alberta. Over the years, he built canoes and other small craft, took up dinghy sailing, and raced and crewed on various boats. He bought and refurbished a 16-foot, gaff-rigged plywood Lark designed in the late 1800s that he still sails occasionally.

Living on Vancouver Island in British Columbia, Jan wasn’t necessarily looking for a boat to purchase, but his interest was piqued by a local listing for a C&C 27 Mark V. He bought the boat in 2015 and renamed her Infinity. Soon Jan, wife Martine, and son Sam sailed her off to Desolation Sound at the northern reaches of the Salish Sea, and many cruises and daysails followed.

Design & Construction

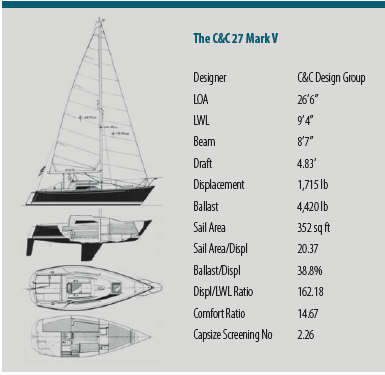

The C&C 27 Mark V was developed in the early 1980s by the C&C design team led by Rob Ball and Neil Gilbert to replace the aging Mark I-IV series. First launched in 1984, the more performance-oriented design was slightly shorter, a few inches wider, and almost 1,000 pounds lighter. During the Mark V’s production run, which lasted until 1987, more than 300 were made.

Improvements and modifications during the production years made subtle changes to the design. This review is focused on the 1985 version produced in Rhode Island. (For a history of C&C Yachts, see GOB’s September/ October 2002 issue). The hull of the Mark V, like its predecessor, is solid glass with a balsa-cored deck that incorporates plywood where deck hardware is mounted. Relatively hard bilges lead aft to a slightly reversed transom. Instead of a rudder post through the cockpit floor of the earlier models, the Mark V has a transom-mounted spade rudder, providing extra space in the cockpit and ease of maintenance.

The hull-to-deck joint is an outward-turned flange with the deck bolted through the anodized aluminum toerail. Through-bolts and bedding compound bond the hull to the deck. With the hull flange turned outward, access to the fastener nuts is outside the hull behind a vinyl cover — very convenient when occasional tightening is required.

The 4-foot 10-inch lead fin keel has a modern vertical profile, versus the shark fin style of the earlier designs. It is bolted to the shallow bilge sump. A factory option was a shoal-draft keel at 3 feet 6 inches, with an additional 360 pounds to compensate for the shallower draft.

Deck & Rigging

True to C&C’s design approach of the time, the 27’s deck is all angular flat planes with soft edges, quite a change from the rounded design of earlier models. This works very well when attaching hardware, since there are no radically rounded surfaces to compensate for when installing flat hardware. The coach roof slopes toward the small foredeck in a gentle, pleasing angle, with a hatch located just before the foredeck. The tall, single-spreader masthead rig is stepped on a cast aluminum plate with plenty of attachment points for turning blocks. Infinity was set up with some serious racing gear. The mast has a groove in the forward edge for a spinnaker pole car with blocks top and bottom. This groove is simply a rounded slot with no provisions for bearings of any kind; adjustment under load may prove difficult.

All lines from the mast lead to triple-stacked deck organizers on the coach roof and then back to line stoppers and Barlow 10 winches at the trailing edge of the roof — very convenient for singlehanded sailors. There is no need to go forward to the mast when underway.

The upper and lower stays meet at the same chainplate, which could cause mast pumping in heavier seas. There is a provision for a detachable baby stay on Infinity, but it is rarely used. The chainplates are bolted to the bulkhead in the main cabin and readily accessible. There is no indication of water intrusion on the bulkhead.

Long genoa tracks on the sidedeck are set well inboard, allowing for close sheeting angles. There is also a short jib track abeam of the mast at the top edge of the cabin trunk. This permits serious windward sheeting when the small jib is up in heavier airs. The backstay is split — perfect for simple tension-adjusting hardware.

The slotted black anodized aluminum toerail helps keep dropped tools on deck, and more importantly, provides unlimited fastening points for turning blocks. The stanchions and pulpits are rigged for double stainless steel lifelines, with a properly supported gate at the forward end of the cockpit. Interestingly, the stanchion bases are a polycarbonate material and show no signs of wear or damage.

The length of the cockpit is generous for a hull of this size. The 6-foot 2-inch seats are long enough for a nap, but not quite wide enough for a good sleep. A deep cockpit locker is accessible through a large hatch on the starboard side. A pair of two-speed Barient 21 self-tailing primary winches is mounted on the coamings forward of where the helms-person would sit — perfect for singlehanded sail handling. There is no room for additional spinnaker winches on the narrow coaming top. The coamings are relatively low and provide limited back support. Access to the slightly sloped sidedeck is unobstructed.

The tiller intrudes into the cockpit but is easily lifted out of the way. A simple tiller extension allows for seating on the cockpit coaming, or even the sidedeck when heeled over. The diesel engine control panel is under the tiller on the transom, out of the way of errant feet, with the throttle control forward in the footwell. The mainsheet traveler crosses the companionway; the mainsheet does obstruct access to the companionway, but is well positioned for the singlehanded helmsperson.

Sails

The previous owner of Infinity was definitely a racer! With the adjustable backstay, spinnaker gear, and sail inventory, this boat was meant to compete. Aside from the mainsail, Infinity came with four headsails and three spinnakers. The fully battened mainsail and 120% genoa with foam luff are in very good condition. Two symmetrical (0.5-ounce and 0.75-ounce) spinnakers and one asymmetrical complete the sail inventory. On our test sail, we did not have the opportunity to hoist a spinnaker.

Accommodations

This racer/cruiser has a surprisingly generous, well-thought-out interior for a 27-foot boat with a 9-foot beam. Oiled teak bulkheads and trim nicely complement the light fabric and headliner. Headroom, however, is a challenge at 5 feet 10 inches.

The galley is immediately to starboard, with a countertop two-burner propane range. This allows for more storage under the stove but eliminates an oven. The moderately sized insulated icebox is located in the corner of the counter between the stove and stainless steel sink. Adding insulation to the icebox would be a challenge. The sink has a hand water pump, which could be easily upgraded to a foot or electric pump.

To port is an open quarter berth that is a very comfortable single, or a double for a couple of youngsters. There is a mid-height open storage shelf that extends all the way to the forward bulkhead; a previous owner enclosed some of the shelf for extra storage capacity.

The cabin table is mounted against the teak bulkhead and slides amidships before folding down — a clever solution. A teak door provides a degree of privacy from the main cabin, but there is no such illusion of privacy for the V-berth. Earlier editions of the Mark V had an accordion-style door installed between the head and V-berth. On Infinity, the bulkhead is cut away on the starboard side to visually open up the forward cabin. The head and sleeping quarters share the space.

The forward hatch is directly above and allows for stargazing while drifting off to the perfect night’s sleep. It also provides excellent ventilation through both cabins. Unfortunately, the hatch is the only source of ventilation. With the hatch and companionway closed in foul weather, a Dorade-type vent would be most welcome.

Mechanical

Unlike the original C&C 27s, which offered an outboard motor option, the Mark Vs were commissioned with a diesel engine installed under the cockpit sole behind the companionway steps. Considering that the engine compartment is uninsulated and open to the cockpit locker, I was pleasantly surprised by the minimal vibration and noise encountered while motoring. An enclosed, sound-insulated compartment would go a long way to reducing even that noise.

There is easy access to the raw-water pump and oil filter behind the companionway steps. Access to the primary and secondary fuel filters, along with the transmission, is through the large cockpit locker. A single starting battery is located beside the transmission with the single deep-cycle house battery in the cockpit locker. There is room for an additional house battery if desired, but a flat space would have to be created. The 12-gallon aluminum fuel tank is mounted behind the engine with a cockpit deck filler.

Underway

Backing out of the slip under power was entirely predictable, and the Yanmar provided plenty of thrust to maneuver in tight spaces with the two-blade Gori feathering prop. The direct feel of a transom-hung rudder close to the propeller made directional control positive.

Out in the open, the lightweight boat quickly reached a cruising speed of 5 knots at 2,800 rpm, significantly below the rated continuous output of 3,400 rpm — leaving plenty of power in reserve when required.

The wind was light when we hoisted the mainsail and rolled out the 120% genoa, perfect for a lightweight flyer like the C&C 27 Mark V. Infinity ghosted along in the fickle wind, accelerating briskly with every gust. In cruising mode more wind would probably be welcome, just to get the boat approaching hull speed. The IOR-influenced design that C&C favored in the 1980s produced excellent windward performance. Working to windward in the light breeze, I found tacking to be effortless and the effects of proper sail trim immediately apparent. The boat was a joy to sail. I could picture myself thrashing to windward in a fresh breeze, the tiller light to the hand while seated on the leeward gunnel. Unfortunately, that wasn’t to be. The wind all but evaporated as the afternoon progressed.

If you’re interested in club racing, the C&C 27 Mark V has just a few small fleets around the country, with PHRF numbers between 177 and 191 seconds per mile. Compare this to the venerable Catalina 27, introduced much earlier, in 1971, which comes in at 210; the Cal 3-27 of 1983, which rates 192; and the speedy J/27 of 1984, which rates 129 seconds per mile.

Conclusion

It had been years since I had sailed a tiller-steered boat, and sailing the C&C 27 brought back many fond memories. The instant feedback that a tiller provides should be part of every sail training program. As successful as the original C&C 27s were, the Mark V was a significant leap forward in design. Production of this successful design probably would have continued had C&C not ceased operations due to financial difficulties. No, the boat does not have many of the “necessary” onboard amenities of more modern, tubby 27-footers, but it sails exceptionally well while providing basic cruising comfort. Instead of resorting to the iron genny in light airs, a C&C 27 sailor can ghost along in quiet satisfaction, sailing as a sailor should. Solid C&C construction and reliability are benchmarks worth retaining into the future.

We found quite a few used C&C 27 Mark Vs for sale on sailboatlistings.com, with asking prices ranging from around $9,000 to $14,900.

Bert Vermeer and his wife, Carey, live in a sailor’s paradise. They have been sailing the coast of British Columbia for more than 40 years. Natasha, an Islander Bahama 30, is their fourth boat (following a Balboa 20, an O’Day 25, and another Islander Bahama 30). Bert tends to rebuild his boats from the keel up. Now, as a retired police officer, he also maintains and repairs boats for several nonresident owners.

Thank you to Sailrite Enterprises, Inc., for providing free access to back issues of Good Old Boat through intellectual property rights. Sailrite.com